Tea and Jesuits II

In 1561, Juan Fernández, a lay member of the Society of Jesus, recorded the adoption of tea at the Jesuit residence where Damien, a young Japanese convert, “has the task of always having a kettle of hot water ready, which he gives to all the visitors and to those in the residence who want it. This the custom of the country.”[1] Although not entirely clear, the Fernández commentary may be the first suggestion of Europeans regularly taking tea. More certain were the accounts of the Jesuit Luis d’Almeida who noted that “the Japanese are very fond of an herb agreeable to the taste, which they call chia”[2] and described tea as a “delicious drink once one becomes used to it”[3] as if making an enthusiastic recommendation of the herb.

Luis d’Almeida was a Portuguese physician who arrived in Japan in 1556 aboard a merchantman.

Tea and Jesuits I

The birth of the Jesuit mission in Asia was intimately linked to the Lisbon royal court and Portuguese ambitions for empire. In the first voyage to the East Indies, Portugal sent a small fleet under the command of Vasco da Gama.

His forces landed in India at Calicut, “the City of Spices” in 1498, marking a harsh and persistent Portuguese presence along the west coast of the subcontinent that lasted for centuries. Defeating the Bijapur sultanate and capturing Goa in 1510, conquistadors established the port city as the administrative seat of Portuguese India; explorers then ventured to Malacca, the Spice Islands, and China, where the Portuguese acquired the island port of Macao. Continue Reading →

Looking for Lu Hongjian

Jiaoran (730-799 A.D.) of the Tang dynasty

Looking for Lu Hongjian but Not Finding Him

You moved beyond the city wall,

Where the rural path crosses mulberry and hemp,

Near a planted hedge of chrysanthemum,

Not blooming, though autumn has come.

Knocking on your door, no answer, not even the bark of a dog.

Wishing to leave, I asked your neighbor to the west.

He said you go off into the mountains,

Returning with each setting sun.

Picking Lotus

Xiao Gang (a.k.a. Emperor Jianwen di, reign 549-551) of the Liang dynasty

Picking Lotus

Late sun warms the deserted jetty,

Picking lotuses by evening’s glow.

Wind rising; the lake crossing, hard.

So many lotuses, undiminished by the harvest.

The oar moves, the petals fall.

The boat sways, the white egret takes flight.

Lotus silk entwines about our wrists,

Water caltrop pulls at our sleeves.

Cha and Te

The character 茶 for tea was pronounced differently in different Chinese dialects. Seafaring merchants sailing from their native ports in southern China spoke a number of local and regional languages, including the widely disparate Cantonese of Guangdong province and the Amoy of Fujian. While trading in Southeast Asian waters, along the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian island of Java, the Chinese encountered early European traders at the port cities of Malacca, Bantam, and Jayakarta and introduced the Westerners to tea. When speaking of the plant and leaf, the Chinese used the distinct languages of their different provinces.

The Cantonese pronounced the word tea as cha.[1] Cha also happened to be the spoken word for tea in the widespread Mandarin dialect. Linguistically, Cantonese and Mandarin together covered nearly three quarters of the country, that is to say, cha was the dominant pronunciation for tea throughout China. Tea as 茶 and cha extended beyond the continent to Korea and Japan, where the plant and herb were introduced from China as an important commodity and a feature of high culture and foreign diplomacy. Continue Reading →

On the Love of the Lotus

Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073) of the Song dynasty

On the Love of the Lotus

Among flowering plants in water or earth, many are much admired. During the Jin dynasty, Tao Yüanming cherished only the chrysanthemum. And since the Tang dynasty of the imperial Li family, everyone has been enamored of the peony. But I especially love the lotus, for it rises from the mud unstained, cleansed in rippling water, appealing, yet not seductive. The center of the stem is unobstructed and clear; outside, it is straight, not tendrilled nor branched. At a distance, its fragrance is all the purer. Planted in elegant stands, the lotus is esteemed from afar and not to be trifled with. I call the chrysanthemum the recluse of flowers. The peony is the richest and aristocratic of flowers. The lotus is the gentleman of flowers. Alas, for admirers of the chrysanthemum after Tao Yüanming, few are known. For love of the lotus, who can ever match me? As for devotees of the peony, is it any wonder there be such a crowd! Continue Reading →

Tsia and Cha

Before the English term “tea,” the words “tsia,” “tcha,” and “chia” were all early Western attempts to replicate cha, the Chinese pronunciation of the written character 茶 meaning tea.[1] As the first Europeans to sail to China in 1513, the Portuguese were also the first to hear the word cha 茶 spoken in Chinese at Macao and other Asian ports of call.

Thirty years later, they landed in Japan and heard the similar name cha 茶 in Japanese at the port of Hirado. To represent the Asian words for tea, Portuguese mariners and merchants engaged in phonetic substitution and used the Latin alphabet to reproduce the sound. Thereafter, the Romanized word “cha” generally sufficed for early written reports about the herb to Lisbon. But there was a problem. In the early sixteenth century, there was little consensus as to the spelling of ordinary European words let alone foreign names like cha and tea. Among Lusitanian writers, the spelling of foreign words was a matter of personal choice or style or phonetics. In the case of tea, the Benedictine monk Gaspar da Cruz italicized and spelled it “ch’a”[2] and the Jesuit Luis d’Almeida wrote it as “chia,”[3] while the adventurer Fernão Mendes Pinto chose the unitalicized “cha” sans apostrophe.[4] Initially influenced by reports from Lisbon and Rome, other Europeans later began to adopt Chinese and Japanese words in their vernaculars. Lacking their own rules of spelling, however, the rest of Europe struggled to represent cha in their respective languages.[5]

Among English and French writers of the seventeenth century, cha was written “tcha.”[6] German writers were indiscriminate, one giving tea six names at different points in his description, including ”tsia,” “tzai,” and “cha.”[7] And in a single study of the plant, a German physician referred to tea as “tsia,” “tsja,” “tsjaa,” “ta,” and “sa,” among other names.[8] Compounding the Western chaos over spelling, there was the added confusion of tea having more than one Chinese name. Europeans learned that cha 茶 was also pronounced te 茶.

Notes

[1] The modern Chinese reading of the character 茶 for tea is romanized in the pinyin romanization system as cha. The obsolete English spellings of tea “tsia,” “tcha,” and “chia” attempted to reproduce cha, a sound made of the consonantal ch and the vowel a. The sound ch is a digraph of two characters, c and h, representing a single consonantal sound or phoneme. As a sound, ch is familiar to English speakers as the “ch” sound in “chip.” In Chinese, the sound ch may be represented by the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol /t∫/ which in phonology is described as a voiceless postalveolar affricate (or voiceless palato-alveolar affricate or domed postalveolar affricate). In Japanese, the similar sound ch may be represented by the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol /ʨ/ which in phonology is described as a voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate. When the consonantal ch is combined with the vowel a the sound cha is formed: [t∫a] and/or [ʨa], a combination of the ch sound as in “church” with a long, soft a as in “father.” In the mouth, the sound is produced by raising the tongue to the hard palate (alveopalatal) with a stop (affricate [t]) immediately followed by forcing the breath through the tongue, palate, and upper front teeth (fricative [∫]), lowering the tongue and jaw, opening the vocal tract, and voicing the low vowel [aː]. For a study of the words for tea, see Victor H. Mair and Erling Hoh, “The Genealogy of Words for Tea,” The True History of Tea (London: Thames and Hudson, 2009), Appendix C, p. 264.

[2] Gaspar da Cruz, O.P. (Portuguese, circa 1620-1670), Tratado da China (1569) in South China in the sixteenth century: being the narratives of Galeote Pereira (Portuguese, active ca. 1549-1561), Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, O.P., Fr. Martín de Rada, O.E.S.A. (Spanish,1550-1575) (London : Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1953), pp. 140 and 214 and Aniceto dos Reis Gonçalves Viana (Portuguese, 1840-1914), Apostilas aos Dicionários Portugueses (Lisbon, 1906), vol. I, pp. 272-275.

[3] Letter from Luis d’Almeida, S.J. (Portuguese, 1518-1584) published in Giovanni Pietro Maffei, S.J. (Italian, 1533–1603), Le istorie dell’ Indie Orientali (Paris, 1572, Florence, 1588, and Cologn, 1589), Francesco Serdonati, trans. (Bergamo, 1749), bk. VI, p. 171.

[4] From the papers of Fernam Mendez Pinto (Portuguese, 1510-? after 1558) acquired from his widow in João de Lucena (Portuguese, 1500-1600), História da Vida do padre Francisco Xavier do que Fizeram na Índia os Mais Religiosos da Companhia de Jesus (Lisbon, 1600) Book VII, ch. 4; S. Rodolfo Dalgado, Influencia do Vocaulario Portugues em Linguas Asiaticas (Lisbon: Academy of Sciences, 1913), vol. 1, pp. 50-51; and Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado and Anthony X. Soares Portuguese vocables in Asiatic languages: from the Portuguese original of Monsignor Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, Anthony X. Soares, trans. (New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1988), Volume 1, pp. 93-95, esp. 94.

[5] Donald F. Lach, “Rebabelization,” Asia in the Making of Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977), vol. 2, bk. 3, pp. 532-541.

[6] Mercurius Politicus, no. 435, September 30, (London,1658), first recorded tea advertisement, booked by The Sultaness Head Coffee House, London (The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 1971), vol. I, p. 371); Philippe Sylvestre Dufour (French, 1622-1687), Traitez Nouveaux & Curieux du Café, du Thé et du Chocolate (Lyons: Adrian Moetjens, 1685), chs. 1-5, pp. 193-256, esp. 195; and Pierre Pomet (French, 1658-1699), Compleat History of Drugs (1694) (London: 1712), vol. 1, ch. 5, p. 84.

[7] See the comments of Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo in Adam Olearius (German, 1603-1671), Beschreibung der Muscowitischen und Persischen Reise (Voyages and travels of the ambassadors sent by Frederick Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy, and the King of Persia, Compleat history of Muscovy, Tartary, Persia & the East Indies; a.k.a. Voyages & travels of the ambassadors from the Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy, and the King of Persia, begun in the year M.DC.XXXIII. and finish’d in M.DC.XXXIX; and Voyages & travels of Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo (German, 1616-1644), a gentleman belonging to the Embassy, sent by the Duke of Holstein to the great Duke of Muscovy, and the King of Persia, into the East-Indies, 1656), John Davies, trans. (London: John Starkey and Thomas Basset, 1669), book II, p. 147, book II, p. 156, and book VI, p. 222, respectively.

[8] Engelberto Kaempfero (German, 1651-1716), Amoenitatum exoticarum politico-physico-medicarum fasciculi v, quibus continentur variae relationes, observationes & descriptiones rerum Persicarum & ulterioris Asiae, multâ attentione, in peregrinationibus per universum Orientum, collecta, ab auctore (Five fascicles of exotic pleasures regarding politics, physics, and medicine, which contain various relations, observations, and descriptions of Persian matters and regions beyond Asia collected through various expeditions through the entire Orient by the author) (Lemgoviae, Typis & impensis H.W. Meyeri, 1712), fasciculus III, observatio 13, pp. 605 and 608 and fasciculus V, Plantarum Japonicarum, Classis 2, Plantus pomiferus & Nuciferus, p. 817 and Englebert Kaemper, Exotic Pleasures: Fascicle III Curious Scientific and Medical Observations, Robert W. Carrubba, trans. (Library of Renaissance Humanism, 1996), pp. 141 passim.

Poem of Desires

Lu Yü (circa 733-804 A.D.) of the Tang Dynasty

Poem

I do not desire cups of white jade

Nor covet wine vessels of yellow gold.

I do not yearn for court matins

Nor long for evening audiences.

I have instead a thousand yearnings,

Ten thousand longings for the western waters of the river

Flowing just beyond the walls of Jingling.

唐陸羽

詩

不羨白玉盞

不羨黃金罍

亦不羨朝入省

亦不羨暮 入臺

千羨萬羨西江水

曾向竟陵城下來

Source

Li Zhao 李肇 (active circa 802-821 A.D.), Tang Guoshi bu 唐國史補 (Supplement to the History of the Tang Dynasty, 9th century A.D.), jüan 2 卷中

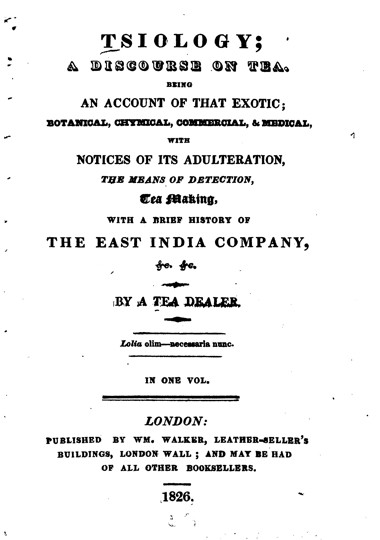

Tsiology and the OED

The term “tsiology” was introduced in the book title Tsiology; A Discourse on Tea in 1826. For over one hundred years, the word remained obscure until 1933 when it was included in the Oxford English Dictionary.

According to the OED , “tsiology” was derived from the obsolete root word “tsia” meaning tea. The lexicon did not include a phonetic transcription but noted that “tsia” was pronounced like the words “tcha” and “chia.”[1] The dictionary further observed that “chia” was “an early form of the word TEA”[2] and moreover that “chia” was once introduced into the English language but no longer survived in general use. Obsolescence of all three terms “tsia,” “tcha,” and “chia” further confused the matter.

James Murray and the other editors of the OED dubbed “tsiology” an ad hoc or nonce word.[3] As a nonce word, “tsiology” was a figure of speech created to meet a need that was not expected to recur, and so it was used just “for the nonce” as the leading title of A Discourse on Tea. Strictly speaking, “tsiology” was a hapax legomenon, a unique word that occurs only once in a single work.[4] More accurate still, “tsiology” was a neologism, a term minted to extend the meaning of the existing word – “ology” – by combining it with the unique prefix “tsi,” the contraction of “tsia.” “Hence,” as the Dictionary intoned, “Tsiology, a scientific dissertation on tea.”[5]

Notes

[1] “Tcha” and “chia” were two other discarded words also defined as tea. The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 1971), vol. II, p. 3425.

[2] OED (1971), vol. I, p. 394.

[3] OED (1971), vol. II, p. 3425. The phrase nonce word was introduced as an attributive by James Augustus Henry Murray (Scottish, 1837-1915) when he oversaw the creation of the New English Dictionary, what would later become the OED.

[4] The appearance of “tsiology” on the two title pages of the book notwithstanding.

[5] OED (1971), vol. II, p. 3425.

Tsiology

In 1826, a small book was published in London bearing the curious name Tsiology; A Discourse on Tea. Like many previous treatises written in Europe, Discourse dealt with the nature of the exotic Asian plant Camellia sinensis and its leaf. Yet, no title on the subject of tea was ever so strange as Tsiology.

Lengthy subtitles provided the content of the book: “being an Account of that Exotic; Botanical, Chymical, Commercial, & Medical, with notices of its adulteration, the means of detection, Tea Making, with a brief history of The East India Company, etc.”[1] But the word “tsiology” was still difficult to fathom, and parsing the term merely hinted at a special branch of knowledge or science.

“Tsiology” defied discovery in the dictionaries of the day, but its exclusion from the English lexicon was easily explained: the word was pure invention. Expressly coined for the book, “tsiology” appeared just once in the title and not at all in the text,[2] leaving the origin and true meaning of the term a profound mystery. That the author, “A Tea Dealer,” remained cloaked in anonymity further muddled the matter.

Nonetheless, Tsiology briefly intrigued London readers with its veneer of erudition, the novel work and title lasting through three editions printed over a year or so.[3] Although the book dealt with several important and timely issues of the British tea trade, “tsiology” never gained popularity as an expression of tea, and indeed it all but disappeared from the common English language.

Notes

[1] The full title of the book read Tsiology; A Discourse on Tea, being an Account of that Exotic; Botanical, Chymical, Commercial, & Medical, with notices of its adulteration, the means of detection, Tea Making, with a brief history of The East India Company, etc. For a list of early books on tea, see John Coakley Lettsom (English, 1744–1815), The Natural History of the Tea-Tree (London: Edward and Charles Dilly, 1772), pp. 8-12.

[2] “Tsiology” was used as the title twice in the book: once on the half title page and then on the title page.

[3] Alfred Rehder (American, 1863-1949), The Bradley Bibliography: A Guide to the Literature of the Woody Plants of the World Published Before the Beginning of the Twentieth Century (Riverside Press, 1915), vol. 3, p. 606.

Ode to Tea

Du Yü (ca. 282-311 A.D.) of the Western Jin Dynasty

Ode to Tea

On Mount Ling is a high peak where

a wondrous thing gathers.

It is tea,

filling the valleys and covering the hills,

moist with the wealth of the Earth,

blessed with the sweet spirit of Heaven.

In the first harvest moon,

the farmers get little rest.

Couples at the same task,

searching and picking.

Take water from the flowing river Min,

draw from its pure currents.

Select bowls from lustrous wares

produced in Eastern Ou.

Serve tea with a gourd ladle,

emulating the way of Duke Liu.

Only then can one begin to perfect

thick froth, afloat with the splendor of the brew,

glistening like piling snow,

resplendent like the spring florescence.

Chaste and true like new frost,

pure like the Void,

tea harmonizes the spirit, blending within,

languidly free, effortlessly Empty.

西晉杜毓

荈賦

靈山惟嶽

奇產所鍾

厥生荈草

彌谷被崗

承豐壤之滋潤

受甘靈之霄降

月惟初秋

農功少休

結偶同旅

是采是求

水則岷方之注

挹彼清流

器澤陶簡

出自東隅

酌之以匏

取式公劉

惟茲初成

沬沉華浮

煥如積雪

曄若春敷

若乃淳染真辰

色責青霜

白黃若虛

調神和內

慵解慷除

Primary source

Yiwen leijü 藝文類聚 (Encyclopedic Collection of Writings by Category, 624 A.D.), Ouyang Xun 歐陽詢 (557-641), et al., comps. , juan 卷 82, no. 1.9.