Excerpt from the Rhapsody on the Capital of Shu

Yang Xiong of the Han dynasty

Excerpt from the Rhapsody on the Capital of Shu

…Thus,

The Five Grains are abundant,

The squashes and gourds, aplenty, and

The many plants yield thatch and hemp.

Everywhere is ginger and gardenia,

Monkshood and great garlic,

Flowering shrubs and wormwood,

Pepper and riverweed.

The sundry gels, pastes, and sweet wines,

All gathered, presented, and stored.

In winter, the bamboo nurtures shoots

To accompany the daily dishes.

The Hundred Flowers burst forth in spring

Filling the air with gentle perfume.

Tendrils and tea, lushly profuse,

Jade green, russet, and celadon,

Glorious as luminous dragon scales,

Spread like rich embroidery and

Vast prospect without end…

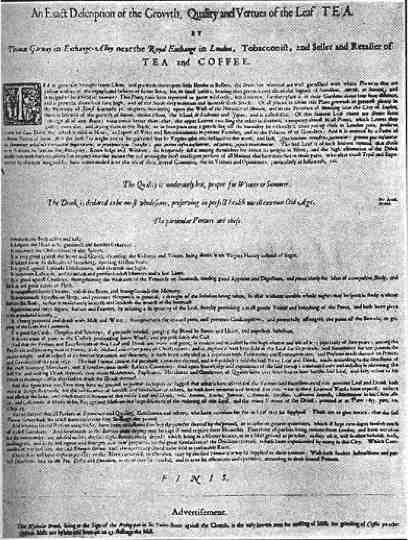

Thomas Garway’s Broadsheet Advertisement for Tea, circa 1668

“An Exact Description of the Growth, Quality, and Vertues of the Leaf TEA, by Thomas Garway in Exchange Alley, near the Royal Exchange in London, Tobacconist, and Seller and Retailer of TEA and COFFEE.

“An Exact Description of the Growth, Quality, and Vertues of the Leaf TEA, by Thomas Garway in Exchange Alley, near the Royal Exchange in London, Tobacconist, and Seller and Retailer of TEA and COFFEE.

Tea is generally brought from China, and groweth there upon little Shrubs or Bushes, the Branches whereof are well garnished with white Flowers that are yellow within, of the bigness and fashion of sweet Brier, but smell unlike, bearing thin green leaves about the bigness of Scordium, Mirtle, or Sumack, and is judged to be a kind of Sumack: This Plant hath been reported to grow wild only, but doth not, for they plant it in their Gardens about four foot distance, and it groweth about four foot high, and of the Seeds they maintain and increase their Stock. Of all places in China this Plant groweth in greatest plenty in the Province of Xemsi, Latitude 36. degrees, bordering upon the West of the Province of Honam, and in the Province of Namking, near the City of Lucheu; there is likewise of the growth of Sinam, Cochin China, the Island de Ladrones and Japan, and is called Cha. Of this famous Leaf there are divers sorts (though all of one shape) some much better than the other, the upper Leaves excelling the other in fineness, a property almost in all Plants, which Leaves they gather every day, and drying them in the shade, or in Iron pans over a gentle fire till the humidity be exhausted, then put up close in Leaden pots, preserve them for their Drink Tea, which is used at Meals, and upon all Visits and Entertainments in private Families, and in the Palaces of Grandees. And it is averred by a Padre of Macao Native of Japan, that the best Tea ought not to be gathered but by Virgins who are destined to this work, and such, Qua nondum Menstrua patiuntur; gemma qua nascuntur in summitate arbuscula servantur Imperatorie, ac pracipuis ejus Dynastis: qua autem infra nascuntur, ad latera, populo conceduntur.[1] The said Leaf is of such known vertues, that those very Nations so famous for Antiquity, Knowledge, and Wisdom, do frequently sell it amongst themselves for twice its weight in Silver, and the high estimation of the Drink made therewith, hath occasioned an inquiry into the nature thereof among the most intelligent persons of all Nations that have travelled in those parts, who, after exact Tryal and Experience by all Wayes imaginable, have commended it to the use of their several Countries, for its Vertues and Operations, particularly as followeth, viz. Continue Reading →

Ascending the White Rabbit Pavilion in Chengdu

Zhang Zai of the Western Jin

Ascending the White Rabbit Pavilion in Chengdu

Corners bind the city’s inner walls,

Wing swept eaves mount storied pagodas.

Rooftops pierce the heavenly clouds,

Tall spires ascend into the Void.

High pavilion, the open crimson door:

The view, an unbroken panorama.

To the west, the river Min and mountain ridges:

Lofty Mount E looms larger than the peaks of Jing and Wu.

Great taro patches cover the land,

Plains and marshes grow grains and greens.

Even when compared to the time of Yao and Tang,

Food is ever abundant.

In myriad small towns,

Crowd the common folk.

The streets, confused, a tangle of fine silk threads;

Roofs and rafters invade the boulevards.

I wish to ask about Master Yang’s abode

And to see the home of the Elder Minister.

Cheng and Zhuo piled up thousands in gold,

As proud and prodigal as the Five Marquises.

They ride marvelous mounts and

Wear jade belts and swords from Wu.

Their bronzes filled with foods of the Four Seasons,

Blending aromas, wonderful and rare.

But truly, I’d rather be in the woods picking autumn oranges

And on the nearby rivers angling for spring fish:

Black fry tastier than fish sauce,

Fruit more luscious than crab dip.

Fragrant, beautiful tea crowns the Six Purities,

Its overflowing flavor spreads through the Nine Regions.

If only life were that peaceful,

This world would hold more pleasure.

The Accomplished Man

Zuo Si of the Jin dynasty

Poem Eight from Eight Poems on History

Flap, flap, a caged bird

Beating wings against four corners.

Aloof, aloof, the backstreet scholar,

A brooding shadow kept to an empty house.

Going out, there is no exit,

Brambles block the way.

Dreams are abandoned,

Like fish out of water.

On the street – no measure of fortune;

At home – not a measure saved.

Constantly belittled by relations,

Day and night neglected by friends.

Su Qin propagandized in the north and

Li Si memorialized in the west, but

Aspiring to glory and splendor, tsk,

Is just carving rotten wood.

Drinking from the river fills the belly,

But one can drink only so much.

A forest nest need perch but on a single branch:

Such is the way of the accomplished man.

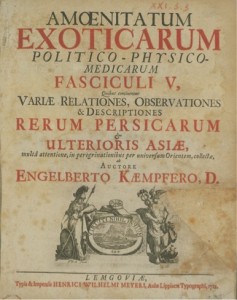

Engelbert Kaempfer on Tea and Bodhidharma

The Japanese legend of the discovery of tea by the first Zen Patriarch Bodhidharma graphically detailed the dedication of the master to meditation. According to the story, Bodhidharma, known as Daruma in Japan, practiced a strict regimen of meditation at the Shaolin Temple outside the ancient Chinese capital of Luoyang by sitting in a nearby cave and facing the wall. He meditated in this fashion for many years until one day, without realizing his fatigue, he fell asleep. Angered by his inability to stay awake and concentrate, he ripped out his eyelids and flung them to the ground. Miraculously, the flesh sprouted into tea plants at his feet. Tasting the leaves, he felt refreshed and clear minded and immediately resumed meditation. His habit of tea was passed to his disciples and through them to the whole Buddhist community. Such was the origin of tea explained in Japanese folklore.

The first ever literary expression of the Bodhidharma tea story appeared to have been written in Latin by the German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716 A.D.) while serving as surgeon to the Dutch East India Company. Between 1690 and 1692, Kaempfer was stationed at Deshima, the small island connected to the Japanese port of Nagasaki. A gifted botanist and keen observer, he wrote one of the most complete descriptions of tea of the time, noting not only the plant but also its Japanese name, cultivation, harvest, types of tea, preparation, preservation, use, virtues and vices, and implements and utensils for making and serving tea. In 1712, Kaempfer published his study of tea as “Theae Japonensis historia” in the third fascicle of Amoenitatum Exoticarum, otherwise known as Exotic Pleasures, and included the popular image of Bodhidharma depicted crossing the Yangzi River on a reed as well as the legend of the origin of tea. Continue Reading →

The first ever literary expression of the Bodhidharma tea story appeared to have been written in Latin by the German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716 A.D.) while serving as surgeon to the Dutch East India Company. Between 1690 and 1692, Kaempfer was stationed at Deshima, the small island connected to the Japanese port of Nagasaki. A gifted botanist and keen observer, he wrote one of the most complete descriptions of tea of the time, noting not only the plant but also its Japanese name, cultivation, harvest, types of tea, preparation, preservation, use, virtues and vices, and implements and utensils for making and serving tea. In 1712, Kaempfer published his study of tea as “Theae Japonensis historia” in the third fascicle of Amoenitatum Exoticarum, otherwise known as Exotic Pleasures, and included the popular image of Bodhidharma depicted crossing the Yangzi River on a reed as well as the legend of the origin of tea. Continue Reading →

Tea and Bodhidharma

The discovery of tea was ever a story of many dimensions, and the telling of the tale depended on the leaf’s use as medicine, food, or drink. Throughout history, tea was intimately related to deities, demi gods, and mortals. In Japan, the monastic use of tea as an aid to meditation was celebrated by linking the plant and its origins to Bodhidharma, the first Patriarch of Zen Buddhism.

Bodhidharma was a Buddhist monk who traveled from India to China around the year 475 of the Common Era. Some thirty five years earlier, he was born a Brahman of the Hindu faith and a prince of the southern Indian kingdom of Pallava. He converted to Buddhism in his youth and was instructed by his teacher to go to China. Arriving by ship on the south China coast, he spent fifteen years traveling to various courts and monasteries, teaching along the way. Sometime around 490, he crossed the river Yangzi and headed north to the capital of Luoyang where he lived until his death in 528. Continue Reading →

Drinking from the Dragon’s Well

Dragon Well is fed by a clear mountain spring near beautiful West Lake. In ancient times, the spring’s cold, pure waters gathered in a pool known as Longhong that lay sheltered deep within an old forest. Remote and secluded, the pool became the haunt of hermits seeking solitude and tranquility.

Dragon Well is fed by a clear mountain spring near beautiful West Lake. In ancient times, the spring’s cold, pure waters gathered in a pool known as Longhong that lay sheltered deep within an old forest. Remote and secluded, the pool became the haunt of hermits seeking solitude and tranquility.

According to legend, the pool Longhong was silent and placid, but when agitated, the waters emitted a low, mournful sigh, and a mysterious, undulating, liquid coil snaked along the rippling surface and then slowly disappeared. These strange signs marked the watery lair of the benevolent dragon that protected West Lake and the old city of Hangzhou nearby.

Lured by the weird effluence and its resident spirit, wizards and alchemists swirled the wondrous waters from the “well of the dragon” into their elixirs and potions. Tasting sweet and light, the water from Dragon Well lent its name, Longjing, to the green tea grown in the nearby valleys and terraced hills.

Memories of Pu’er Tea

Pu’er cha 普洱茶 is a hot Chinese drink familiar to almost anyone eating in an old Hong Kong style restaurant and drinking its tea. In such a place and in times long past, Pu’er was the only tea of consequence. This was especially true in San Francisco’s Chinatown, which in the early 1950s was packed, cheek by jowl, with dives like the Buddha Lounge and green grocers and a myriad restaurants, big and small.

Pu’er cha 普洱茶 is a hot Chinese drink familiar to almost anyone eating in an old Hong Kong style restaurant and drinking its tea. In such a place and in times long past, Pu’er was the only tea of consequence. This was especially true in San Francisco’s Chinatown, which in the early 1950s was packed, cheek by jowl, with dives like the Buddha Lounge and green grocers and a myriad restaurants, big and small.

At the high end of the culinary scale was Kan’s, a posh establishment with a gold and scarlet interior, plush drapes and upholstered chairs, where suave waiters paraded in slicked back hair, starched white shirts, bowties, and black vests, serving exotic bird’s nest soup and sauced sea cucumbers. Kan’s menu raised the bar, attracting well heeled patrons, politicians, and movie stars.

A humbler affair but equally famous, Sam Wo occupied a unique spot on the eat-o-meter. Housed in a narrow space squeezed tightly between two buildings, the sparsely furnished upper floors were reached only by brushing past fiery stoves and wiry cooks wielding cleavers and woks. Sizzling and splattering, the tiny kitchen dished out congee 粥, fen 粉, and noodles 麵, the “three harmonies” for which Sam Wo 三和 was named.

Sam Wo’s questionable charm was perversely enhanced by rickety stools and wobbly tables and a notoriously insolent waiter. Choosing the unlikely name Edsel Ford Fong, he roundly entertained everyone by gruffly abusing each customer while expertly tossing about clattering plates of savory chowmein, bowls of wonton, and mounds of sliced raw fish with slivers of red ginger over crisped noodles.

Sam Wo’s questionable charm was perversely enhanced by rickety stools and wobbly tables and a notoriously insolent waiter. Choosing the unlikely name Edsel Ford Fong, he roundly entertained everyone by gruffly abusing each customer while expertly tossing about clattering plates of savory chowmein, bowls of wonton, and mounds of sliced raw fish with slivers of red ginger over crisped noodles.

Regardless of the place chosen – high or low – Kan’s or Edsel’s – once seated, all were welcomed by a steaming pot of tea served out in a small cup as a matter of custom and courtesy, and because a proper meal always began with Pu’er.

On the weekends, Pu’er tea was essential when observing yumcha 飲茶, literally to “drink tea,” an occasion when whole families met for brunch over rounds of dimsum 點心, the nearly endless array of savory fare that was so expensive to create that only restaurants offered it, so dizzyingly rich that it was served just in small portions, and so utterly satisfying that it “dotted the heart.” As each delicious morsel was consumed, empty pots were replenished and cups refilled, the Pu’er sipped slowly to cleanse the palate in anticipation of the lush flavors of the next tempting dish. As plates piled up and bits of gossip flew about the table, drinking Pu’er tea aided digestion, stemmed the tide of triglycerides, and cleared foggy heads. And in those empty moments of soft silence, a sip of Pu’er and a pensive nod helped fill the conversation.

On the way home, a stop at the Chinese grocery store acquired the week’s household quota of loose Pu’er packed in a small square tin. Back at the house, opening the box revealed an inner lid and inside that, a cellophane bag chock full of dark brown leaves mixed with twigs and stems. When opened, the tea filled the nose with the scent of dry wood and dirt.

A heaping tablespoon fed a perpetual Pu’er that filled the old porcelain pot, kept warm in a wicker cozy, the tea shared by young and old throughout the day quenching thirst, refreshing the mind, restoring vigor, and lifting the mood.

The tea was drunk all year round, but in summer or hot weather dried chrysanthemum blossoms were added for their cooling effect. To treat a cold or for just a treat, children drank Pu’er poured steaming hot over a piece of preserved fruit such as longan, jujube, or lemon peel that flavored the tea. When the tea was finished, the juicy bit was a tasty prize sucked and swallowed. On Chinese holidays, crystallized ginger, sugared coconut and lotus root were traditional favorites for sweetening life and cups of Pu’er.

As with all good things – polished rice, sesame oil, fragrant soy, and fine vinegar – Pu’er tea was indispensable, and its very presence the certain sign of a prospering and stable home.

Characteristics of the Tea Leaf, 1653 A.D.

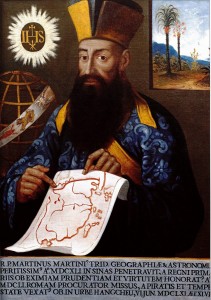

Martino Martini of the Society of Jesus

Characteristics of the Tea Leaf

There is nothing superior to the famous tea leaf. To satisfy the curious reader and students of botany, here is a brief description:

The small leaf is wholly like that produced by Rhus Coriaria, sumac; however, I am not persuaded that it is of the same species. It is not wild but cultivated, not a tree but a bush that spreads in various branches and twigs, nor does the flower differ much from that of the sumac, except that the white color tends somewhat to yellow. In summer, the flower is fragrant with a light perfume; the green berry follows, and then blackens. To brew the drink Cha, the first tender leaves of spring are sought and gathered, carefully and individually by hand. Then the leaves are warmed a little over a slow fire in an iron pan, and then placed on a matt and rolled by hand, and then fired and rolled again until curled and quite dry. The tea is kept in containers of tin, its essence carefully preserved against all humidity. Even kept after a long while, when cast into boiling water, the leaves uncurl and return to their original greenness. If the tea is of the best quality, the fragrance is sweet and the taste not unpleasant, once used to it, and suffuse with a greenish color. Though many deprecate the virtues and power of this hot beverage, the Chinese drink it often, day and night, and welcome friends with it. Moreover, many varieties of superior tea rise in price to over two gold pieces per pound. Those who drink tea get neither gout nor stones. After eating, it relieves indigestion and aids digestion. Tea may be taken to alleviate inebriation, to refresh and reinvigorate, to relieve hangovers, and it may be used as a diuretic to dispel extraneous fluids. Tea is for those who wish to remain awake and banish sleep and to ward off drowsiness from those who want to study. In China, tea is named after its locale, such as the excellent and famous Sunglo cha. For a fuller description of tea, see the work published in French by Alexander de Rhodes, who describes tea more at length, in the section, Kingdom of Tunking part I, chapter 15.

Cha folium quale.

Folium Cha nominatissimum nusquam alibi, quam hic praestantius est. id in gratiam curiosi lectoris, ac Botanices studiosi brevibus describam:

Foliculum est omnino illi simile, quod rhus coriaria profert, imo illius quandam esse speciem tantum non mihi persuadeo, non tamen sylvestre illud, sed cultum est, non arbor, sed virgultum est, quod in ramulos varios, aut virgulas potius sese diffundit, nec flore admodum differt, nisi quod hujus albedo nonnihil magis in flavedinem declinet; aestate primum florem emittit levi odore fragrantem, sequitur bacca viridior, mox nigricans: pro potione Cha coquenda expetitur folium primum vernum, ac mollius, quod studiose ac sigillatim unum post alterum manu carpunt, mox in ferreo cacabo tenui ac lento igne aliquantulum calefaciunt, deinde supra stoream subtilem ac laevem manibus propellendo involvunt, atque involutum iterum exponunt igni, ac denuo confricant, donec intortum rursus & conglomeratum plane siccum sit: quod servant in vasis plerumque stanneis ab omni humiditate diligentissime & evaporatione custoditum; hoc cum in ebullientem aquam conjicitur etiam post diuturnam asservationem, ad pristinum virorem redit seque expandit, aquam odore suavi, si optimum est, saporeque non ingrato, praesertim ubi adsueveris, ac colore subviridi inficit. Multis hujus calidi potus vires ac virtutem depraedicant Sinae, qui eo noctu & interdiu frequentissime untuntur, hospitesque excipiunt. tanta autem ejus varietas, ac praestantiae discrimen est, ut librae pretium apud ipsos Sinas ab obolo ascendat ad duos plureique aureos: illi potissimum adscribitur, quod Sinae podagram ac calculum nesciant; post cibos sumptum omnem indigestionem ac cruitatem stomachi tollit; maxime enim concoctionem juvat, quin & ab ebriis adhibitum levamen iis, novasque ad potitandum vires affert, adeogue & crapulae omnes molestias levat, siquidem exsiccate & abstergit superfluos humores, ac vigilare cupientibus somniferos vapors expellit, oppressionemque somni studiis vacare volentibus arcet. varia apud Sinas habet nomina; juxta varia loca, eamque, quam obtinet, praestantiam hujus urbis praeclarissimam Sunglocha vocari solet. Pleniorem si quis illius descriptionem desideret, consulat Gallice editum R.P. Alexandrum de Rhodes, qui illud fusius describit, de regno Tunking parte I, cap. 15.

Source

Martino Martini, S.J. (Italian, 1614-1661 A.D.), Novus Atlas Sinensis (New Atlas of China) (Vienna, 1653 A.D.), part 6 of Joan Blaeu (Dutch, 1596-1673 A.D.), Theatrum Orbis Terrarum; sive, Atlas novas (Theater of the World; or New Atlas; a.k.a. Atlas Maior) (Amsterdam: Joan Blaeu, 1662), p. 83.

Compare

Eusèbe Renaudot (French, 1646-1720 A.D.), trans., Ancient accounts of India and China (London: S. Harding, 1733), p. 73; William Crook (English, active ca. 1685 A.D.), The New Relation of the Use and Virtue of Tea printed for W. Crook at the sign of the Green Dragon without Temple Bar, London (1685) cited in Timothy J. Bond, “The Origins of Tea, Cocoa, and Coffee as Beverages,” Teas, Cocoa and Coffee: Plant Secondary Metabolites and Health, lan Crozier, Hiroshi Ashihara, Francisco Tomás-Barbéran, eds. (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), p. 12; Athanasius Kircher, S.J., China Illustrata (1667), Charles D. Van Tuyl, trans. (Muskogee: Indian University Press, 1987), part IV, chap. 6, p. 175; and Bianca Maria Rinaldi, The “Chinese garden in good taste”: Jesuits and Europe’s knowledge of Chinese flora and art of the garden in the 17th and 18th centuries (Munich: Meidenbauer, 2006), pp. 99-100. For the missionary work of Martini, see David E. Mungello, The Forgotten Christians of Hangzhou (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1994), pp. 9-59, passim.

Figure

Artist unknown

European, 17th century A.D.

Portrait of Father Martino Martini, 1661 A.D.

oil painting, inscribed:

“The Reverend Father Martino Martini of Trent,

a man of extraordinary skill in geography and

astronomy, who entered China in the year 1641.

Having been honored by the leading men of the realm

because of his exceptional knowledge and virtue,

he was sent to Rome as a [Jesuit] procurator in the

Year 1651. [During the journey,] he was subjected to

hardship by pirates and storms. He died in the city

of Hangzhou on 6 June 1661 at the age of

forty-seven.” (David E. Mungello, trans.)

Museo Provinciale d’Arte

Buonconsiglio Castle, Trento

Report Submitted to the Commandant

Choe Chiwon of the Silla dynasty

Report Submitted to the Commandant

Wondering, “who from Within the Seas cares for one from without?”

I then ask where to find the river crossing.

I only sought service, not profit;

To honor my family, not myself.

On the journey, a sorrowful parting: rain on the river.

Returning home: a day in dream, touched by spring.

Crossing the water, I happily meet broad, favorable waves:

Each washes from my tassels all ten dusty years.

新羅 崔致遠

陳情上太尉

海內誰憐海外人

問津何處是通津

本求食祿非求利

只爲榮親不爲身

客路離愁江上雨

故園歸夢日邊春

濟川幸遇恩波廣

願濯凡纓十載塵

Source

Choe Chiwon 崔致遠 (최치원, 857- ca. 924 A.D.), comp., Gyewon pilgyeong jip 桂苑筆耕集 (계원필경집, Plowing the Cassia Grove with a Brush, 886 A.D.), ch. 20.

Spoiled Daughters

Zuo Si (250-305 A.D.) of the Western Jin dynasty

Spoiled Daughters

In my house there is a lovely girl,

Exceedingly fair, clear and shining.

Her nursery name is Wansu, White Silk.

Her mouth and teeth are finely formed,

Lush side locks spread across her high brow,

Ears like twin jades.

In the morning, she plays makeup at the comb stands,

Eyebrows blackened as if with a broom.

Thick vermillion slathers cinnabar lips,

Young mouth swelling full and crimson.

Her dainty talk is like tinkling links of jade,

In a temper, her words ring sharp and clear.

When writing, she prefers the red lacquered brush,

But her seal script characters are hopeless.

Holding a book, she delights in the pure silk cover,

During recitations, she boasts of what she’s learned.

Her older sister is Huifang, Gentle Fragrance,

Whose face is splendid like in a painting.

Lightly adorned, she amuses herself about the house.

Before the mirror, she forgets her spinning.

She holds her cosmetic brush, imitating Zhang Chang,

Painting beauty spots, then changing them around.

She plays at putting them on her cheeks, then

Rushes to double her time at the loom.

Calm and composed, she excels at the Zhao dance,

Her outstretched sleeves like wings in flight.

When playing the zither up and down to the very ends of the stops,

Literature and history books are suddenly rolled and folded up.

Glancing at a painted screen,

She is all ready to be critical.

The painting long obscured by dust,

Once clear, its meaning is unfathomable.

Together, the children fly, galloping into the orchard,

Beneath the fruit, picking all the green ones.

Red petals still capped on purple calyxes,

The unripe fruit thrown all about.

Greedy for flowers, even in wind and rain,

They bolt outdoors hundreds of times.

Tramping about on bright snow in play,

Tangled layers of shoelaces in constant jumbles.

Their hearts bent on sumptuous delicacies,

They sit up straight and arrange their saucers and plates.

Brush and ink put away in the writing box,

Often left useless and forgotten.

Seduced by the tea peddler’s gong, they succumb,

Slippered feet rushing out to their pleasure.

So impatient for tea,

They huff and puff at his brazier.

Grease smearing white sleeves,

Smoke staining fine silk.

Their heavily embroidered clothes are

Tough to wash and clean.

Because I let them do as they please,

They are abashed when scolded by elders.

Knowing they’re in for a spanking,

They hide their tears and face the wall.

西晉左思

嬌女詩

吾家有嬌女 皎皎頗白皙

小字為紈素 口齒自清歷

鬢發覆廣額 雙耳似連璧

明朝弄梳台 黛眉類掃跡

濃朱衍丹唇 黃吻瀾漫赤

嬌語若連瑣 忿速乃明劃

握筆利彤管 篆刻未期益

執書愛綈素 誦習矜所獲

其姊字惠芳 面目粲如畫

輕妝喜樓邊 臨鏡忘紡織

舉觶擬京兆 立的成復易

玩弄眉頰間 劇兼機杼役

從容好趙舞 延袖象飛翮

上下弦柱際 文史輒卷襞

顧眄屏風畫 如見已指摘

丹青日塵暗 明義為隱賾

馳騖翔園林 果下皆生摘

紅葩綴紫蒂 萍實驟抵擲

貪華風雨中 眒忽數百適

務躡霜雪戲 重綦常累積

並心注肴饌 端坐理盤槅

翰墨戢函案 相與數離逖

動為壚鉦屈 屣履任之適

止為荼荈據 吹吁對鼎䥶

脂膩漫白袖 煙薰染阿錫

衣被皆重地 難與沉水碧

任其孺子意 羞受長者責

瞥聞當與杖 掩淚俱向壁

Source

Xü Ling 徐陵 (507-583 A.D.), Yütai xinyong 玉臺新詠 (New Poems from the Jade Terrace, ca. 545 A.D.), juan 卷2 and Qüan Han Sanguo Chin Nanbei chao shi 全漢三國晉南北朝詩 (The Complete Poetry of the Han, Three Kingdoms, Chin and Northern and Southern Dynasties), Ding Fubao 丁福保 (1874–1952 A.D.), comp. Taibei: Shijie shujü, 1969), vol. 1, ch. 4, pp. 387-388.

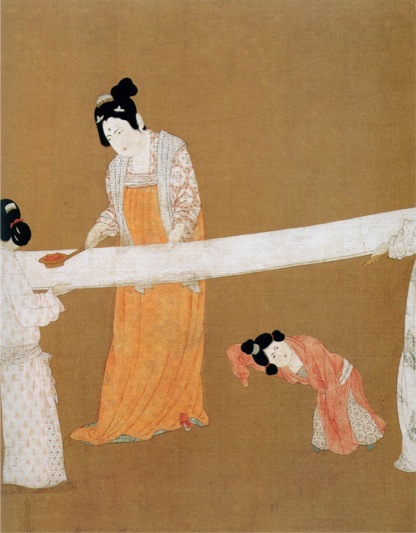

Figure

Emperor Huizong 徽宗 (1082–1135 A.D.), attributed to

Daolian tu 搗練圖 (Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk, early 12th century A.D.)

Northern Song Dynasty

Handscroll: ink, color, and gold on silk, details

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Special Chinese and Japanese Fund 12.886

A Song of Drinking Tea to Chide the Envoy Cui Shi

Jiaoran (730-799 A.D.) of the Tang dynasty

A Song of Drinking Tea to Chide the Envoy Cui Shi

The man from Yüe presented me with Shan River tea;

Picking the golden buds, brewing them with a bronze brazier.

In a plain, snow-white porcelain, a fragrant, misty froth.

Does this not transcend the elixir of the immortals?

The first drink washes away confusion and sleep –

a clear, bright feeling fills Heaven and Earth.

The second drink purifies my spirit –

a sudden, flying rain lightly scatters the dust.

The third drink simply achieves the Dao –

no need to fuss about banishing troubles and cares.

Of this pure and lofty thing, the world is unaware.

People drinking wine only deceive themselves:

Fretting about the night Bi Zhuo lay soused under the wine vat;

Laughing at the time Tao Qian lay drunk under the hedge.

Lord Cui drinks tea relentlessly, as if

Insanely singing a single tune, shocking everyone.

Who knows the true Way of Tea?

Only Danqiu attained this.

唐皎然

飲茶歌誚崔石使君

越人遺我剡溪茗

採得金牙爨金鼎

素瓷雪色縹沫香

何似諸仙瓊蕊漿

一飲滌昏寐

情來朗爽滿天地

再飲清我神

忽如飛雨洒輕塵

三飲便得道

何須苦心破煩惱

此物清高世莫知

世人飲酒多自欺

愁看畢卓瓮間夜

笑向陶潛籬下時

崔侯啜之意不已

狂歌一曲驚人耳

孰知茶道全爾真

唯有丹丘得如此

Source

Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 821, no. 61.

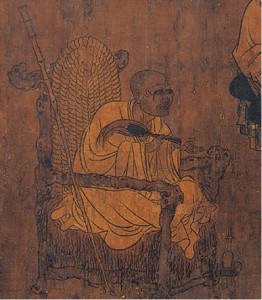

Figure

Yan Liben 閻立本 (ca. 601-673 A.D.), attributed to

The monk Biancai 辯才(flourished circa 600-649 A.D.)

Xiao Yi zuan Lanting tu 蕭翼賺蘭亭圖 (Xiao Yi Stealing the Orchid Pavilion Preface)

Tang dynasty

Handscroll: ink and color on silk, detail

National Palace Museum, Taipei