Miscellaneous Poem

Wang Wei of the Liu Song dynasty

Miscellaneous Poems, number one of two

Alone and desolate, I close the high chambers,

Silent and empty, the grand halls.

Waiting for my lord who will not return,

I catch myself and go at once to tea.

王微

王微

雜詩二首 其一

寂寂掩高閣

寥寥空廣廈

待君竟不歸

收领今就檟

Source

Wang Wei 王微 (415-453), “Zashi 雜詩 (Miscellaneous Poem),” Chajing 茶經 (Book of Tea, 780 A.D.), Lu Yü 陸羽 (trad. 733-804 A.D.), comp. (Baichuan xüehai 百川學海, ed., 1273 A.D.), juan 3, part 7, p. 7b.

Figure

Gu Kaizhi 顧愷之 (ca. 345-406), attributed

Nüshi zhentu 女史箴圖 (The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies), detail

Handscroll: ink and colors on silk

The British Museum

London

New Imperial Tribute Tea from Huzhou

Zhang Wengui of the Tang

New Imperial Tribute Tea from Huzhou, ca. 841

On a spring outing, returning tipsy by phoenix carriage,

Her coiffed peony blossoms teasing bobbled ornaments.

Fording the inlet, the faerie belle peeps through the screen

To announce the arrival of russet buds from Wuxing.

唐 張文規

唐 張文規

湖州貢焙新茶

鳳輦尋春半醉回

僊娥進水御簾開

牡丹花笑金鈿動

傳奏吳興紫筍來

Source

Zhang Wengui (active 830–853), “Huzhou gongbei xincha 湖州貢焙新茶 (New Imperial Tribute Tea from Huzhou, ca. 841) in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 366, no. 11.

Figure

Zhou Fang (ca. 730-800)

Court Ladies Wearing Flowered Headdresses, 8th century

Handscroll: ink and color on silk

Liaoning Provincial Museum

The Ten Virtues of Tea

Liu Zhenliang of the Tang dynasty

The Ten Virtues of Tea

Take tea to dispel melancholy, banish sleep, increase vitality, expel disease, initiate decorum and humanity, express respect, cultivate sophistication, nurture the body, harmonize with the Dao, and regulate desire.

唐 劉貞亮

茶十德

以茶散鬱氣

以茶驅睡氣

以茶養生氣

以茶驅病氣

以茶樹禮仁

以茶表敬意

以茶嘗滋味

以茶養身體

以茶可行道

以茶可雅志

Source unknown

Liu Zhenliang 劉貞亮 (a.k.a. Liu Zhende 劉貞德 and Jü Wenzhen 俱文珍, active 787-813), imperial eunuch and respected supervisory commander of the Xüanwu Army 宣武監軍 at Kaifeng; rewarded by the emperor with the posthumous title Commander Unequalled in Honor 開府儀同三司.

Stories About Lu Yü

Feng Yan (active ca. 755-794 A.D.)

Record of Things Heard and Seen

Chapter 6

“Drinking Tea”

In the Discourse on Tea, Lu Hongjian of Chu explained the merits and methods of brewing and toasting of tea, devising twenty-four tea implements and using an elegant case in which to store them. Near and far, everyone imitated him, and every proper household kept a case of tea implements. Because of his teachings and embellishments, Lu Hongjian, as well as Zhang Boxiong, created a great movement in the art of tea. Princes and nobles and courtiers without exception all drank tea. Li Jiqing, the Censor in Chief, was sent to inspect the Jiangnan region and arrived at the district offices of Huai County. He was told that Zhang Boxiong excelled at tea, whereupon Lord Li summoned Zhang to attend him. Boxiong was dressed in a yellow, sleeveless gown and a black, silk cap, carrying in his own hands his tea utensils. He spoke with authority on the names of tea, showing discernment and giving instruction, expounding on the changes in methods. When the tea was brewed, Li sipped only two cups. Arriving in the Jiangnan region, Li was told that Lu Hongjian was skilled at tea, whereupon Lord Li summoned Hongjian to attend him. Hongjian wore rustic robes and entered accompanying his tea implements. After sitting, he earnestly gave instruction just as Boxiong had done. But in his heart, Li despised him. When the tea was over, Li ordered a servant to take thirty coins to pay “Doctor Tea Cook.” Having traveled widely throughout the south, Hongjian was intimately familiar with fame and celebrity, but this was a shameful incident to which he reacted by writing the Discourse on the Ruination of Tea.

封演

飲茶

封氏聞見記

卷六

楚人陸鴻漸為《茶論》,說茶之功效並煎茶炙茶之法,造茶具二十四事,以都統籠貯之。遠遠傾慕,好事者家藏一副。有常伯熊者,又因鴻漸之論廣潤色之。於是茶道大行,王公朝士無不飲者。御史大夫李季卿宣慰江南,至臨懷縣館,或言伯熊善茶者,李公請為之。伯熊著黃衫、戴烏紗帽,手執茶器,口通茶名,區分指點,左右刮目。茶熟,李公為歠兩杯而止。既到江外,又言鴻漸能茶者,李公復請為之。鴻漸身衣野服,隨茶具而入。既坐,教攤如伯熊故事。李公心鄙之,茶畢,命奴子取錢三十文酬煎茶博士。鴻漸游江介,通狎勝流,及此羞愧,復著《毀茶論》。

Yan Zhenqing (709-785 A.D.)

“Inscription on the Stele along the Spirit Path of the Honorable Master Li, Grand Master of the Palace with Gold Seal and Purple Ribbon, Acting Grand Mentor of the Heir Apparent, Concurrent Chamberlain for the Imperial Clan, Chief Minister, Minister of Works, Supreme Pillar of State, and Dynasty-founding Duke of Longxi County,” excerpt

Complete Literary Works of the Tang Dynasty

Chapter 342

His Eminence Li Qiwu was demoted to Prefect of Jingling Prefecture. At the time, Lu Yü Hongjian accompanied the Master on a tour of inspection of the region. Lu Yü stated that Li Qiwu stepped from his carriage and summoned his officers, saying to them: ‘Among officials, there are those who do not cultivate the sacred rites; among Buddhists and Daoists, there are those who are incompetent at monastic discipline; and among the common people, there are those who are reckless and impulsive. Before my taking office, none were held responsible. But from now onward, offenders will be relentlessly pursued.’ Within a number of years, the state of the prefecture completely changed, and Jingling flourished and prospered as in the golden age of the ancient sage emperor Fuxi.

顏真卿

金紫光祿大夫守太子太傅兼宗正卿贈司空上柱國隴西郡開國公李公神道碑銘

全唐文

卷三白四十二

公遂貶竟陵郡太守。時陸羽鴻漸隨師郡中,說公下車召人吏告之曰:“官吏有簠簋不修者,僧道有戒律不精者,百姓有泛架蹶馳者,未至之前,一無所問,而今而后,義不相容。”數年間一境丕變,熙然若羲皇之代矣。

Li Zhao (flourished circa 818-821 C.E.)

Supplement to the Dynastic History of the Tang, 827 A.D.

Chapter 3

In the Jiangnan region, there was a station master who did things his own way. When the governing prefect arrived on an official tour of inspection, the station master simply said, “The station is all in order. Please make your review.” Thereupon, the prefect proceeded. He first saw a room with the sign “Wine Storage” where various drafts were brewed. On the outside of the room was painted the image of a deity. The prefect asked, “What is this?” To which the station master answered, “That is Du Kang, the Sage of Wine.” The prefect then said, “Everywhere this is so.” At another room, the sign read “Tea Storage,” where tea was stored, and again there was an image of a deity. “What is that?” “That is Lu Hongjian, the Sage of Tea.” The prefect thought it was excellent and approved. At another room, the sign read “Pickle Storage,” where pickles were prepared. Again, there was a deity. “What is this?” The official said, “Cai Bojie.” The prefect laughed out loud, saying: “No need to display this!”

李肇

唐國史補

卷下

江南有驛吏,以干事自任。典郡者初至,吏白曰:“驛中已理,請一閱之。”刺史乃往,初見一室,署雲“酒庫”,諸醞畢熟,其外畫一神。刺史問:“何也?”答曰:“杜康。”刺史曰:“公有余也。”又一室,署雲“茶庫”,諸茗畢貯,復有一神。問曰:“何?”曰:“陸鴻漸也。”刺史益善之。又一室署云「葅庫」,諸葅畢備,亦有一神。問曰:“何?”吏曰;“蔡伯喈。”刺史大笑曰:“不必置此。”

Zhou Yüan (active ca. 773-816 A.D.)

“Composing Three Expressions of Being Moved after Visiting West Pagoda as Metropolitan Governor of Jingling”

Complete Literary Works of the Tang Dynasty

Chapter 620

The writings of the ancients included banners and funerary palls, songs of the meritorious, the heterodoxy and apocrypha, and works cherishing the past: flags of praise were posthumously bestowed; songs of the worthy were genuine expressions of form; the unorthodox were simply eccentric and unconventional; reverence for the bygone revealed true human feeling. In contrast, casting inscriptions in bronze and carving them in stone aggrieve the spirits. These are not respectful but rather quite maudlin. And what of my writings, do they revere the past? Objectively speaking, what are they to be taken as?

I, Zhou Yüan, who having written “His Honor Ma Zong of Fufen and his Military Commission over the One Hundred Ethnic Minorities,” formerly worked with the Honorable Li Fu of Longxi, Governor of Nanhai. Li Fu was ordered to move to Huatai. When Ma joined me on Li’s staff, it was in Lingnan at Rongzhou and Guangzhou for about seven meteoric years. Now, Ma Zong’s meritorious contributions fill the world, his literary compositions fly forth from his brush, and as Military Commissioner of Nanhai, he is mother and father to its people. By comparison, I, Zhou Yüan, as a mere provincial governor, just look frail and weak. But, we two are enveloped with one another like “twin carp,” each of us harboring deep regard for the regions of Chu and Yüe. Li Fu, however, lived but a short life and died young. This indeed is the first expression of being so moved and stirred!

Li Fu’s father was the late Li Qiwu, who was a man of great virtue and Governor of Jingling. Because he was born during his father’s days as governor, Li Fu was given the name Fu. Alas! I, Zhou Yüan, who carelessly and disgracefully administers Li Qiwu’s province, was on Li Fu’s staff, and I now govern his father’s prefectural realm. Alack! Li Qiwu! In the official residence, the songs and bells are now extinguished, and Li Qiwu has been buried these many years – now only tears and lamentations. This is indeed the second expression of being so moved and stirred.

For many unbroken years, the Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent Lu Yü and I were aides together in Li Fu’s office. Lu Yü was truly my brother! In his Autobiography, Lu wrote he was from Jingling. At the time, he said, “Jingling is beautiful. There is no place better than my hometown.” Now, I administer his town of Jingling. Remembering his words, Lu Yü truly did not exaggerate. Ma Zong also knew Lu Yü. Speaking on his behalf, Ma addressed Lu Yü’s background. Lacking records in the ancestral shrine, Lu Yü began life as a foundling, and until he came of age at nineteen, he lived the life of a Buddhist monk, received Buddhist teachings and its Law, and esteemed the Buddha. A saint, indeed!

Lu Yü, sobriquet Hongjian, a serious scholar of the One Hundred Schools and a companion to half the dignitaries and senior officials under Heaven. He was, moreover, a straightforward and honest critic, a practitioner of witty repartee – a lofty and sublime recluse whose literary works and integrity are incomparable. Ah!

In the west of my prefectural seat, there is Fufu, a place that is round like a mountain top and in the middle of which is a monastery and a pagoda. The bamboo there – as big around as an arm – is a dark green thicket, indeed a living portrait of Hongjian’s teacher. My, such sadness! Resembling a mountain peak, the bamboo of Chu surrounds the pagoda. The abbot whose remains are buried within the pagoda is the same monk who raised and nurtured Lu Yü. The cane in front of the pagoda is the same bamboo once planted and cultivated by Lu Yü.

I look upon the pagoda, the earthly memorial to the elder monk. The bamboo grows old and weathered, and Lu Yü is long gone. As a governor of Chu, I come to Fufu and its Buddhist cloister. It is daylight, and there is no incense burning for Lu Yü. All is abandoned, scattered and lost. My robes tremble in the Chu wind. This is indeed the third expression of being so moved and stirred.

Written in verse, seven characters per line. If Li Fu could read the Three Expressions of Being Moved, how could he hold back his tears and not be sad? Delivered below the pagoda, this composition is Zhou Yüan’s crowning achievement.

周願

牧守竟陵因游西塔著三感說

全唐文

卷六百二十

古人之文,有旌物而為者,歌功而為者,詭時而為者,感舊而為者:旌物,謚也﹔歌功,形也﹔詭時,詐也﹔感舊,情也。若乃折裂金石,騷牢鬼神,莫尚乎感也。予所作者,其感舊耶?客曰:何謂也?

願與百越節度使扶風馬公,曩時俱為南海連率隴西李公復從事 。公詔移滑台,扶風公洎予又為幕下賓,從容兩地,七改星火。今扶風公勛庸滿世,文翰飛走,續鎮南海,(11)作民父母﹔而願才貌單薄,亦為刺史。繇是二客雙鯉 ,殷勤於楚越。隴西短齡閱川而物故,予感一也。

隴西先人諱齊物,彼大德嘗為竟陵郡守。公生於守之日,故名復。嗚呼!願以散拙忝公先人之州,往為子寮,今刺父郡。悲夫!隴西也。歌鍾燼滅於池館,九原極零乎薤露,其感二也。

願頻歲與太子文學陸羽同佐公之幕,兄呼之。羽自傳竟陵人,當時羽說“竟陵風土之美,無出吾國。”予今牧羽國,憶羽之言不誣矣。扶風公又悉於羽者也,代謂羽之出處:無宗祊之籍,始自赤子,洎乎冠歲,為竟陵苾蒭之所生活,老奉其教。如聲聞、辟支,以尊乎竺乾。聖人也!

羽,字鴻漸,百氏之典學鋪在手掌,天下賢士大夫半與之游。加以方口諤諤,坐能諧謔,世無奈何,文行如軻,所不至者,貴位而已矣。噫!我州之左,有覆釜之地,圓似頂狀,中立塔廟, 篁大如臂,碧籠遺影,蓋鴻漸之本師像也。悲歟!似頂之地,楚篁繞塔。塔中之僧,羽事之僧﹔塔前之竹,羽種之竹。視夫僧影泥破,竹枝筠老而羽亦終。予作楚牧,因來頂中道場,白日無羽香火,遐嘆零落,衣搖楚風,其感三也。是為三感說七言詩以語陳事。

扶風公覽三感之說,豈得不酸涕濕目,以著詞致於塔下,冠願鄙章之首邪

Li Fang (925-996 A.D.)

Extensive Records of the Taiping Era, 978 A.D.

Chapter 399

“Lu Hongjian”

In the spring of 814, Zhang Youxin, who had just become famous, arranged to gather with other National University Students of Grace at the Jianfu Temple. Youxin and Li Deyü arrived first and went to rest in the quarters of the monk Xüanjian along the west corridor of the monastery. Just then a monk from Chu arrived and set down a bag to rest. The bag contained several books. Youxin took out a volume and read through it. The writing was all notes and closely detailed. At the end were inscribed the words A Record of Water for Brewing (the word “record” was originally the word “places” according to the emendation of a Ming dynasty copy). In the time of Emperor Taizong [sic], Li Jiqing was governor of Huzhou. When he arrived at Weiyang, he met the recluse Hongjian. Li Jiqing had heard of Lu Yü and was pleased with the chance travel with him. When they arrived at the post station along the Yangzi, it was about dinner time. Li Jiqing said, “Master Lu excels at the art of tea. All under Heaven know this. The water at Nanling along the Yangzi is also exceptional. Today the chance meeting of these two marvelous things is one in a thousand. Why neglect this opportunity?” He ordered a trustworthy and diligent military officer to take a jar and a boat to the deepest part of the Nanling to fetch water. While waiting, Lu Yü cleaned his utensils. Very soon after, the water arrived. Lu Yü used a ladle to scoop out some, saying, “This is indeed river water, but it is not drawn from Nanling. It seems to be water taken from along the shore.” The officer replied, “I rowed the boat and entered the deepest part of the water. This was witnessed by several hundred people. How dare I deceive you?” Lu Yü said nothing, and then he poured from the jar half the water and quickly stopped. Again, he used a ladle to scoop out some and said, “Now this is water from Nanling.” Suddenly startled, the officer hastily knelt and said, “As I was holding the jar level from the Nanling to the riverbank, the boat swayed and the water spilled. Fearing the loss, I added water from the shore. The recluse’s discernment is divine insight, indeed! Who dares conceal or deceive him! Li Jiqing was amazed and filled with admiration. The several tens of bystanders were all shocked and alarmed. Since Lu Yü’s perception was so keen, Li then asked him if he would judge the merits and demerits of water from the places he experienced. Lu said, “The water of Chu is superior. The water of Jin is the most inferior.” Li Jiqing then arranged a sequence of water from places all ranked according to Lu Yü. (This was published as the Book of Water)

李昉

太平廣記

卷三百九十九

陸鴻漸

元和九年春,張又新始成名,與同恩生期於薦福寺。又新與李德裕先至,憩西廊僧玄鑒室。會才有楚僧至,置囊而息,囊有數編書。又新偶抽一通覽焉,文細密,皆雜記,卷末又題雲《煮水紀》(“記”原作“處”,據明抄本改)。太宗朝,李季卿刺湖州,至維揚,遇陸處士鴻漸。李素熟陸名,有傾蓋之歡,因赴郡。抵揚子驛中,將食,李曰:“ 陸 君善茶,蓋天下聞,揚子江南零水,又殊絕。今者二妙千載一遇,何曠之乎!”命軍士信謹者,挈瓶操舟,深詣南零取水,陸潔器以俟。俄水至,陸以杓揚水曰:“江則江矣,非南零者,似臨岸者。”使曰:“某棹舟深入,見者累百人,敢绐乎?”陸不言,既而傾諸盆,至半,陸遽止。又以杓揚之曰:“自此南零者矣。”使蹶然大駭,馳下曰:某自南零赍齊至岸,舟蕩半,懼其尠,挹岸水以增之。處士之鑒,神鑒也,其敢隱欺乎!”李大驚賞,從者數十輩,皆大驚愕。李因問陸,既如此,所經歷之處,水之優劣可判矣。陸曰:“楚水第一,晉水最下。”李因命口佔而次第之。(出《水經》

The Abolition of Caked Tea by Imperial Decree

The Veritable Records of Emperor Taizu of the Great Ming Dynasty

Sixteenth day, ninth lunar month, twenty-fourth year [1391] of the Hongwu reign period

An Imperial Decree on the Jianning Annual Offering of Tribute Tea

Obey: the officials of the tea households are ordered to cease harvesting and presenting caked tea. Of all the empire’s tea producers of annual tribute on fixed quotas, the tea of Jianning is supreme. To produce tribute tea, leaves must be crushed and kneaded into pulp and pressed into silver molds to make large and small dragon rounds, a method that greatly strains the resources of the people. Abolish the production of dragon rounds. Pick only tea buds to present as tribute. There are four kinds: Seeking Springtime; Gathering Springtime; Staying Spring; and Russet Shoots. We established five hundred tea households, exempted them from corvée labor, and allowed them to specialize in planting and harvesting tea. Afterwards, there were officials who feared these later reforms and sent overseers to abuse the householders, who dreaded their tyranny. Everywhere bribes were taken. This was reported to the imperial court. Thus, the emperor issues this command.

大明太祖高皇帝實錄

洪武二十四年九月庚子

詔建寧歲貢上供茶 聽茶戶採進 有司勿與 天下產茶去處歲貢皆有定額 而建寧茶品為上 其所進者必碾而揉之 壓以銀板 大小龍團 上以重勞民力 罷造龍團 惟採茶芽以進其品有四 曰探春 屯春 次春 紫筍 置茶戶五百 免其徭役 俾專事採植 既而有司恐其後時 常遣人督之 茶戶畏其逼迫 往往納賂 上聞之 故有是命

Source

DaMing Taizu gao huangdi shilu 大明太祖高皇帝實錄 (The Veritable Records of Emperor Taizu of the Great Ming Dynasty) 卷之二百十二 (Chapter 212).

Figure

Portrait of Emperor Ming Taizu

Ming dynasty

Album leaf: ink, color, and gold on silk

National Palace Museum, Taibei

Moon Festival

Su Shi of the Song dynasty

Poem

Based on the Song of Water Tunes

Moon Festival, 1076

Happily drinking through the night till morning: Truly drunk, wrote this verse, begging the pardon of younger brother, Ziyou.

When will the bright moon appear?

I raise my wine to query the dark sky,

Wondering what year upon palatial Heaven this night falls.

I wish to return there, immortal on the wind,

But I fear I could not bear the cold heights beneath the jade eaves of its jeweled halls.

Rising to dance in joy with my fine moon-shadow,

There is nothing comparable in all the world.

Moonlight eddies about cinnabar pavilions,

Slips beneath latticed doors,

Shining upon the sleepless.

I should have no regrets,

But as we are apart so long, why then is the moon so round?

We all have joy and sorrow, partings and reunions:

The moon waxes and wanes in shadow and light.

Since ancient times, nothing has ever been perfect.

Long may we live,

Though miles apart, and together enjoy the beauty of the moon!

宋 蘇軾

水調歌頭 丙辰中秋,歡飲達旦,大醉。作此篇,兼懷子由

明月幾時有

把酒問青天

不知天上宮闕

今夕是何年

我欲乘風歸去

又恐瓊樓玉宇

高處不勝寒

起舞弄清影

何似在人間

轉朱閣

低綺戶

照無眠

不應有恨

何事長向別時圓

人有悲歡離合

月有陰晴圓缺

此事古難全

但願人長久

千裡共嬋娟

Guanyin Spring at Tiger Hill

Shen Zhou of the Ming dynasty

Sitting beneath pines quietly sipping tea brewed with water drawn from the Third Spring at Tiger Hill under a waning moon

In the evening, I enquire at the monk’s room where to look for a fine mountain stream.

His attendant guides me to a poor village vendor:

This brewing method is not in keeping with Master Lu’s tea.

Firstly, take and light the bamboo tallies of Master Su.

The stone tripod boils, the draft rousing fine green waves.

See how the porcelain cup holds the moon like a golden bauble!

Beneath the long pines, sips fill with soft songs.

Without poetry, the flavor only withers.

明 沈周

月夕汲虎丘第三泉煑茶坐松下清啜

夜扣僧房覔磵腴

山童道我吝村沽

未傳盧氏煎茶法

先執蘇公調水符

石鼎沸風憐碧縐

磁甌盛月看金鋪

細吟滿啜長松下

若使無詩味亦枯

Source

Shen Zhou 沈周 (1427-1509), “Yüexi ji Huqiu Disanqüan zhucha zuo songxia qingchuai

月夕汲虎丘第三泉煑茶坐松下清啜 (Sitting beneath pines quietly sipping tea brewed with water drawn from the Third Spring at Tiger Hill [in the eighth lunar month] under a waning moon),” Shitian shixüan 石田詩選, ch. 2 in Chen Binfan 陳彬藩 and Yü Yüe 余悅, eds., Zhongguo cha wenhua jingdian 中國茶文化經典 (Beijing: Guangming ribao chuban she, 1999), p. 408.

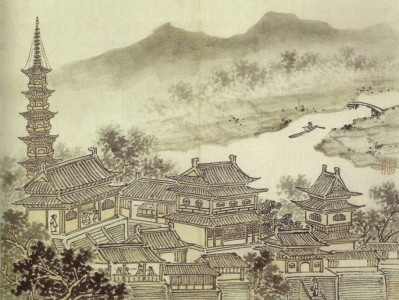

Figure

Shen Zhou (1427-1509)

Twelve Views of Tiger Hill : The Thousand Buddha Hall and the Pagoda of the Cloudy Cliff Monastery

Leaf seven from an album of twelve leaves

Ink and color on paper

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Paradox

Laozi of the Zhou dynasty

Books of the Path and the Power

Paradox

Profound accomplishment appears unaccomplished, yet it is ever present and infinite.

Utter completeness appears incomplete, yet it is ever present and limitless.

True virtue appears as vice.

True art appears artless.

True expression appears inarticulate.

Stillness transcends restlessness, detachment transcends attachment.

Clarity and serenity rectify the world.

悖論

大成若缺其用不弊

大盈若沖其用不窮

大直若屈

大巧若拙

大辯若訥

靜勝躁寒勝熱

清靜為天下正

Source

Laozi 老子, [Beilun 悖論 (Paradox)], Daode jing 道德經 (Books of the Path and the Power in 2 parts.; emended from various sources, huijiaoban 匯校版), part 2, ch. 45.

Figure

Zhao Buzhi 晁補之 (1053-1110 A.D.)

Laozi qi’niu tu 老子騎牛圖 (Laozi Riding an Ox)

China: Song dynasty

Hanging scroll: ink on paper

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Republic of China

Hymn to Tea

Wuzhu of the Tang dynasty

Hymn to Tea

Deep, secluded valleys bear forth the divine herb:

The luminous means to Enter the Way.

Gatherers picking leaves;

Delicate flavors flowing into bowls.

Peace and purity realized,

The Enlightened Mind reveals levels of Awareness.

Effortlessly, without attachment or toil,

The soaring Dharma Gate opens.

唐 無住

茶偈

幽谷生靈草

堪為入道媒

樵人採其葉

美味入流杯

靜虛澄虛識

明心照會臺

不勞人氣力

直聳法門開

Source

Wuzhu 無住 (714-774 A.D.), Chaji 茶偈 (Hymn to Tea), Lidai fabao ji 曆代法寶記 (Record of the Dharma Treasure through the Generations) in Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎, (1866-1945 A.D.) et al., eds., Taishō shinshū Daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (a.k.a. Dazheng xinxiu dazangjing, Taisho Tripitaka, 100 vols.) (Tokyo: Taisho Issaikyo Kankokai, 1924-1934), ch. 51, no. 2075, p. 193b.

A Song of Drinking Tea on the Departure of Zheng Rong

Dedicated to Sylvia and Matthew London for their friendship and generosity

Jiaoran of the Tang dynasty

A Song of Drinking Tea on the Departure of Zheng Rong

The immortal Danqiu abandoned eating jade elixirs,

Picking tea instead, he drank, and grew feathered wings.

The world is unaware of the Mansion of Eminent and Hidden Immortals,

People do not know of the Palace of Transmuting Bone into Clouds.

The Lad of Cloudy Mountain blended it in a gold cauldron;

How hollow the fame of the Man of Chu and his Book of Tea!

Late on a frosty night, breaking cakes of fragrant tea.

Brewed to overflowing, the pale yellow froth; I sip and am reborn.

Bestowed by the gentleman, this tea dispels my suffering,

Cleansing my mind from worry and fear.

Come morning, the emotions of the fragrant brazier remain.

Intoxicated still, we walk across the clouds reflected in Tiger Stream;

In high song, I send the gentleman off.

唐 晈然

飲茶歌送鄭容

丹丘羽人輕玉食

採茶飲之生羽翼

名藏仙府世空知

骨化雲宮人不識

雲山童子調金鐺

楚人茶經虛得名

霜天半夜芳草折

爛漫緗花啜又生

賞君此茶祛我疾

使人胸中蕩憂栗

日上香爐情未畢

醉踏虎溪雲

高歌送君出

Note

For this and other Chinese tea poems, see the forthcoming

THE SPIRIT OF TEA: An Offering To Tea Lovers

a book of photography by Matthew London

Tiger Spring Press, 2014

or go to www.spiritoftea.org

Source

Jiaoran 晈然 (730-799 A.D.), “Yincha ge sung Zheng Rong 飲茶歌送鄭容 (A Song of Drinking Tea on the Departure of Zheng Rong) in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 821, no. 13.

Happy that Tea Grows in the Garden

Dedicated to Sylvia and Matthew London for their friendship and generosity

Wei Yingwu of the Tang dynasty

Happy that Tea Grows in the Garden

Its purity cannot be stained.

Drinking it washes away dust and despair.

This earthly thing truly has an unearthly allure.

My tree is originally from its home in the mountains.

Taking a bit of time from prefectural duties,

I hastily planted it in my tangled garden.

Happily, it thrived full and tall, and now through tea,

I commune with the mystic spirits.

唐 韋應物

喜園中茶生

潔性不可污

爲飲滌塵煩

此物信靈味

本自出山原

聊因理郡餘

率爾植荒園

喜隨衆草長

得與幽人言

Note

For this and other Chinese tea poems, see the forthcoming

THE SPIRIT OF TEA: An Offering To Tea Lovers

a book of photography by Matthew London

Tiger Spring Press, 2014

or go to www.spiritoftea.org

Source

Wei Yingwu 韋應物 (737-792 A.D.), “Xi yüanzhong chasheng 喜園中茶生 (Happy that Tea Grows in the Garden)” in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 193, no. 55.

Tea: A Pagoda Poem

Dedicated to Sylvia and Matthew London for their friendship and generosity

Yüan Zhen of the Tang dynasty

Tea: A Pagoda Poem

Tea

Fragrant leaves, tender buds

The desire of poets, the love of monks

Ground in carved white jade, sifted through red gauze

Cauldron brewed to the color of gold, bowl aswirl in floral foam

At night it welcomes the bright moon, at daybreak it dispels dawn’s rosy mists

Past and present, drinkers are refreshed and tireless, praisefully aware it quells drunkenness

唐 元稹

茶寶塔詩

茶

香葉嫩芽

慕詩客愛僧家

碾雕白玉羅織紅紗

銚煎黃蕊色碗轉曲塵花

夜後邀陪明月晨前命對朝霞

洗盡古今人不倦將知醉後豈堪誇

Note

For this and other Chinese tea poems, see the forthcoming

THE SPIRIT OF TEA: An Offering To Tea Lovers

a book of photography by Matthew London

Tiger Spring Press, 2014

or go to www.spiritoftea.org

Source

Yüan Zhen 元稹 (799-831 A.D.), “Cha 茶 (Tea)” in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 423, no. 24.

Figure

Reconstruction Drawing of the Yongning Temple Pagoda at Luoyang 洛陽永寧寺塔圖

Originally built in 516 A.D. during the Northern Wei Dynasty