Tea in the Han Dynasty

The story of tea is but one of many historical accounts of plants and their benefit to humankind. Discovered millennia ago by hunters and gatherers of the Stone Age, tea was a source of nourishment and medicine. Over time, its use as a food and drug was refined, and tea became part of the culinary and medical repertoire. Classed as a superior drug, tea was noted as a stimulant and relaxant, simultaneously sharpening concentration while soothing without sedation. At table, tea was consumed as a bitter herb and as greens in soups and stews. Valued as a flavoring and vegetable in cooking, tea was commonly combined with other herbs and fruit. Tea as beverage likely derived from medicinal decoctions, the essence of its buds and leaves extracted and concentrated as a liquor by simmering in hot water or by infusion as a tisane. Tea was prized by commoner and aristocrat alike.

Tea was once native to the remote regions of the south where it was first gathered as a wild plant and then later cultivated as a domesticated crop. Whether as wild or cultivated produce, tea was traded, the demand for the leaf influencing the spread of the tea plant to the lower reaches of the Yangzi. In time, much of the south produced tea of such quality that it was exacted as provincial tribute and sent north to the imperial palace during the Han dynasty.

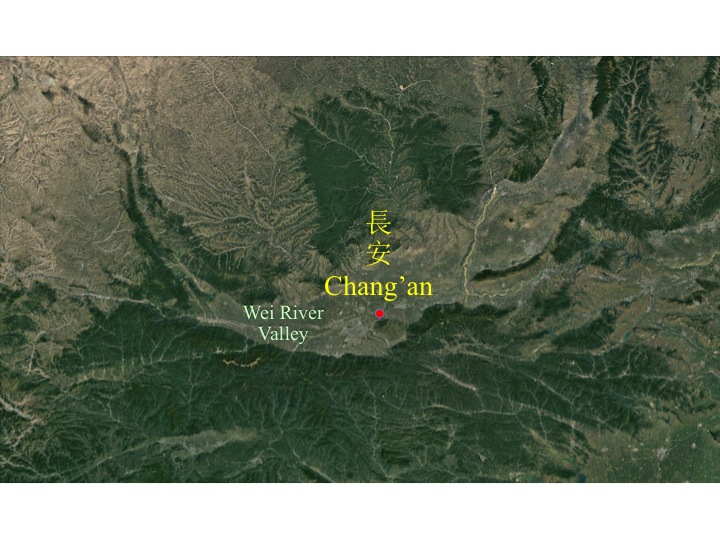

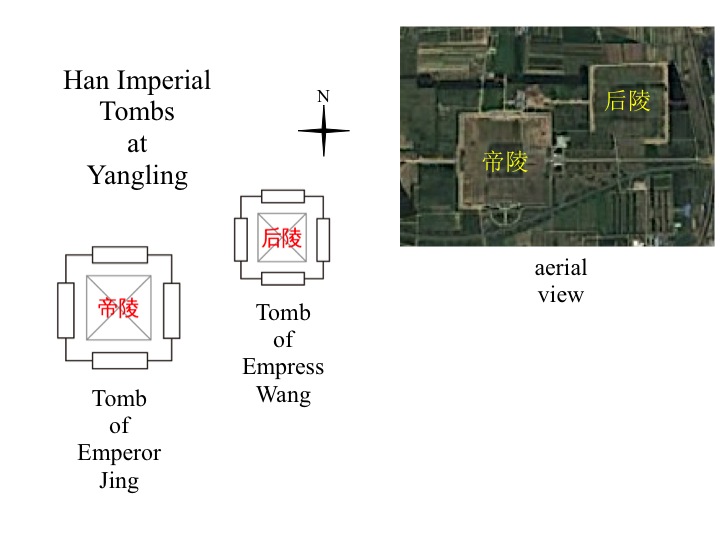

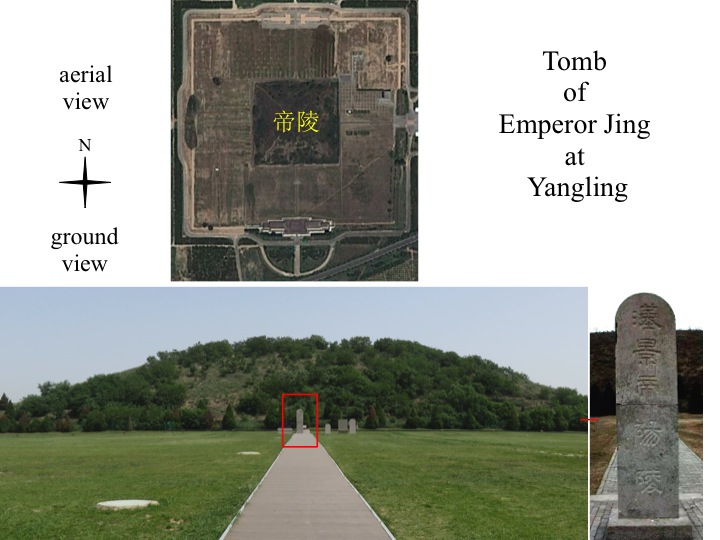

Evidence of tea as tribute was discovered in the Wei River Valley at a Western Han necropolis in the northern suburbs of the ancient capital of Chang’an, present Xi’an, Shaanxi. The site, which is known as the Yangling Mausolea, consists of two pyrimidal mounds, the tombs of Emperor Jing and his empress.

Emperor Jing was the sixth ruler of the Han dynasty; his wife Empress Wang was later buried in an adjacent smaller tomb.

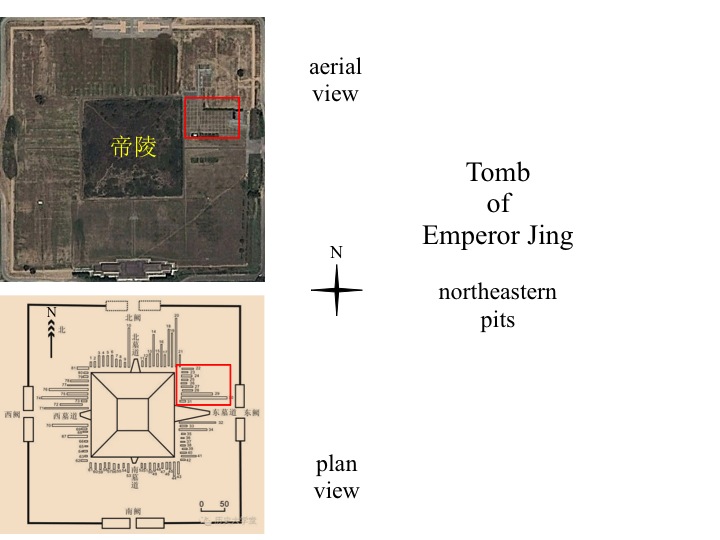

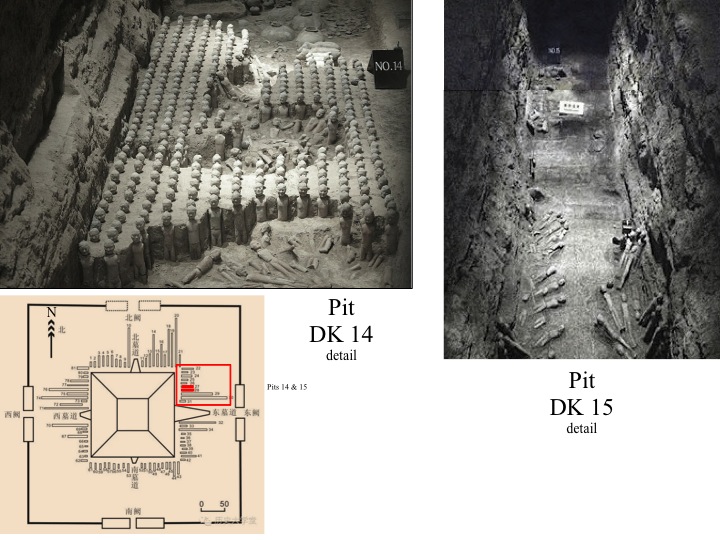

Archaeological investigations of the emperor’s tomb revealed eighty-six outer trenches radiating perpendicular from the four sides of the mound, each long rectangular pit containing funerary goods sacrificed to the dead.

Two pits – designated DK 14 and DK 15 – in the northeast quadrant hold rows of terracotta figures that represent the courtiers, guards, and retainers meant to attend the emperor in the afterlife.

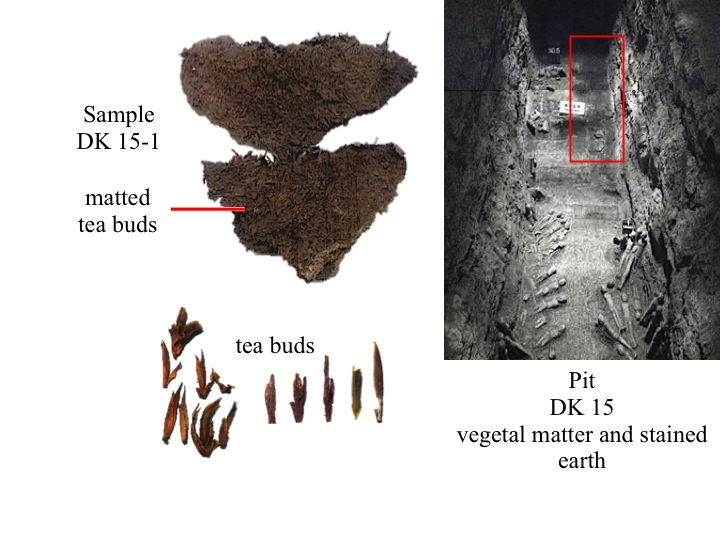

At the eastern end of DK 15, the matted and partially decomposed remnants of organic matter left a large rectangular stain on the earthern floor. Analysis of the fragments showed a mix of seeds, including foxtail millet (Setaria italica), broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), rice (Oryza sativa) and domesticated chenopod (Chenopodium giganteum).

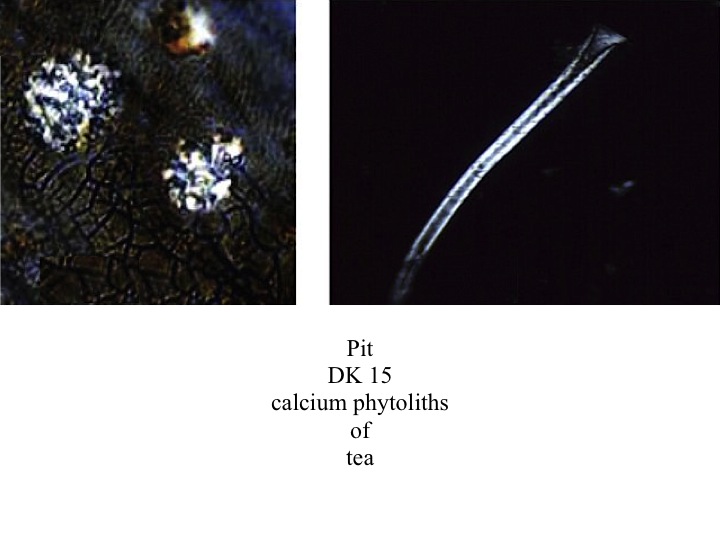

The sample DK 15-1, however, was a mass of plant leaves in a dark brown brick shape: tea. Taxonomic identification of the remnant leaves as tea (Camellia sinensis) was determined by chemical analysis and the examination of plant crystals. Abundant levels of both caffeine and theanine established the leaves as tea, while the ample presence of calcium phytoliths or plant crystals, the types and shapes of which are distinctive to tea, also confirmed the leaves as tea.

The matted remnants of tea revealed that the leaves consisted uniformly of leaf buds, that is to say, only the premium part of the plant was selected and sent to the emperor as tribute. As with all of the other funerary goods in the tomb, the tea was a sacrificial offering to the deceased, and like the grains of millet and rice, probably came from the palace stores.

Sources

Houyuan Lu, Jianping Zhang, Yimin Yang, Xiaoyan Yang, Baiqing Xu, Wuzhan Yang, Tao Tong, Shubo Jin, Caiming Shen, Huiyun Rao, Xingguo Li, Hongliang Lu, Dorian Q. Fuller, Luo Wang, Can Wang, Deke Xu, and Naiqin Wu, “Earliest Tea As Evidence For One Branch Of The Silk Road Across The Tibetan Plateau,” Scientific Reports 6, Article number: 18955 (2016) and Jianping Zhang, Houyuan Lu, and Linpei Huang, “Calciphytoliths (calcium oxalate crystals) analysis for the identification of decayed tea plants (Camellia sinensis L.)” Scientific Reports 4, Article number: 6703 (2014).

Notes

Emperor Jing of the Han (Han Jingdi 漢景帝, né Liu Qi 劉啟, 188-141 B.C.E.), reigned 157-141 B.C.E.

Empress Wang (née Wang Zhi 王娡, 173-126 B.C.E.); consort to Crown Prince Liu Qi, ca. 168 B.C.E.; empress to Emperor Jing, 150 B.C.E.; dowager empress to Emperor Wu, 141 B.C.E.

Baisaō’s Verse on Tea

Kō Yūgai of the Edo Period

Verse on Tea

Going far to China in search of the sacred shoots

Old Eisai brought them back to sow in our land

The taste of Uji tea is imbued with Nature’s essence

Worthy of pity, people talk only of color and scent

Awkwardly done at the request of Nishida Eishi

Written by the eighty-nine year old man, Kō Yūgai

江戸時代 高遊外

茶詩

遠息靈葡入大唐

持歸西老播狀桑

宇陽一味天然戮堪

嘆時人論色香

右拙作應西田英士求

八十九翁 高遊外書

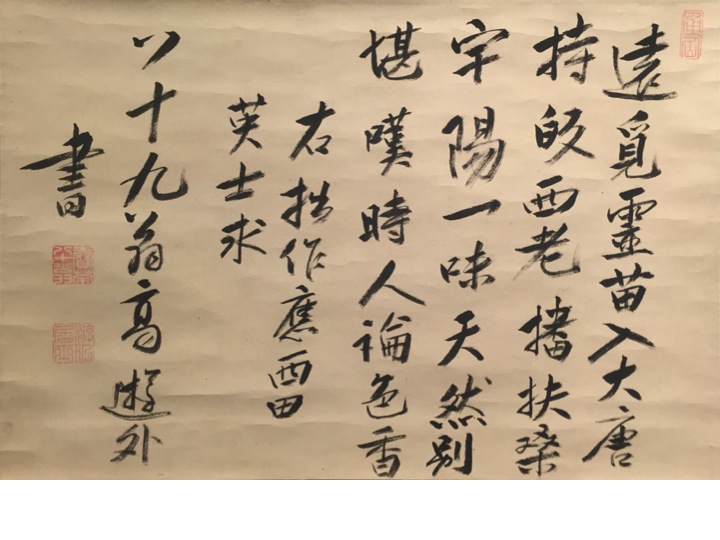

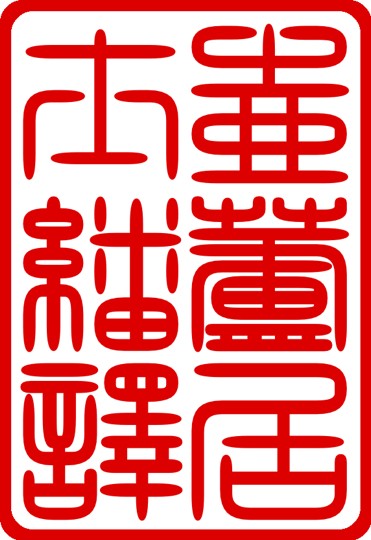

Kō Yūgai 高遊外 was a tea seller who lived in Kyoto during the eighteenth century. At the age of eleven, he became a novice at a Zen monastery affiliated with the Ōbaku sect and took the religious name Gekkai Genshō 月海元昭. After decades as a monk in Kyushu province, he moved to Kyoto where he made a living selling tea, adopting the name Baisaō 賣茶翁, Old Tea Seller. He frequented the scenic spots around the ancient capital, preparing and serving tea to passersby, never charging them but always accepting donations. In his eighties, when he could no long carry his equipage, he burned his tea case and devoted himself to calligraphy. This work on tea was written in the last year of his life.

Note

Compare Norman Waddell, Baisaō, The Old Tea Seller: Life and Zen Poetry in 18th Century Kyoto (Berkekely: Counterpoint, 2008), pp. 118-119.

Figure

Kō Yūgai 高遊外 (1675–1763)

Verse on Tea, 1763

Japan: Edo period

Hanging scroll: ink on paper

41.3 x 27.9 cm.

Saint Louis Art Museum

215:1986

A Little Tea Book

In the introduction to A Little Tea Book, Sebastian Beckwith and Caroline Paul declare that its contents are devoted to the reader, stating that the small volume truly “is for you.” Take them at their word, and you are amply rewarded by clear and simple explanations of the tea plant and leaf in a series of straightforward narratives on over a dozen aspects of tea, many illustrated by Wendy MacNaughton and her vibrant watercolors.

Throughout the little book, tea is presented as stepping stones that cross many borders, “not only geographic boundaries but political, socioeconomic, cultural, and religious ones as well.” Beckwith describes the art of tea as a process of exploration and invites us all to share in the journey, a tea trek captured in part by his many travel photographs and keen eye for detail, but best of all by his stories of searching the remote regions of Asia for the rarest and most elusive forms of the leaf. In just over one hundred twenty pages or so, Beckwith proves to be a singularly outstanding guide.

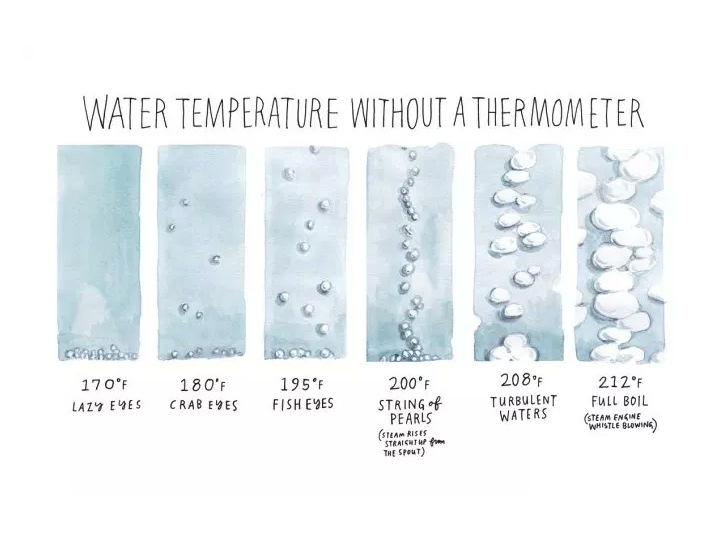

Notable explanations of tea include the distinctions between Camellia sinensis as a plant species, Camellia sinensis sinensis and Camellia sinensis assamica as varietals, as well as tea plants that are bred as cultivars. Beckwith observes the role of the tea green leafhopper (Empoasca (Matsumurasca) onukii Matsuda): the presence and bite of the bug on a leaf produces a defensive response by the plant and the release of chemicals that effect the creation of Oriental Beauty, a wulong tea of exceptional sweetness and aroma. Like the Tang tea master Lu Yu, Beckwith describes water – a much neglected subject in tea – especially the stages of boiling and the look of the hot liquid, all wonderfully illustrated with corresponding temperatures.

Even the scum atop boiled water, which Lu Yu once likened to “dark mica,” is noted and attributed by Beckwith to hard water. Flavors are described as categories: fruit, floral, marine, mineral, sweet, spice, wood, and earth. Vegetal and herbal might qualify as well. Of them all, marine properly describes the fish, seaweed, and kelp flavors of some teas.

Here and there, Beckwith likens tea to fine wine. It is an apt comparison, for the character and quality of bush and vine are influenced by terroir – soil, topography, geology, and climate – the age of the plants, horticulture, harvest, handling, processing, and storage. Indeed, Beckwith goes a step further than analogy and offers several recipes that mix tea and spirits: matcha and shochu, jasmine pearls with vodka, Earl Grey with gin, and sencha and rum.

Perhaps the most important notion in the book is Beckwith’s belief in “rules of thumb rather than rules” regarding the preparation, service, and enjoyment of tea. Rule of thumb is precisely the method used by tea masters from antiquity to the present. The many variables of tea, those changeable factors of water, heat, utensils, and time, require the practice of what the ancients called tasting tea: determining through experimentation how a tea, any tea, is best brewed to exhibit its fullest expression of color, aroma, and flavor.

A Little Tea Book: All the Essentials from Leaf to Cup

Sebastian Beckwith

with Caroline Paul and illustrated by Wendy MacNaughton

New York: Bloomsbury Publishing

2018

Sending Lu Hongjian Off to Pick Tea at Qixia Temple

Huangfu Ran of the Tang

Sending Lu Hongjian Off to Pick Tea at Qixia Temple

Gathering tea is not plucking greens:

Far, far away rises the rim of the cliff.

Leaves cloaked by a warm spring wind,

Baskets filled by sunrise.

Old friends on the temple path,

Now and then spending the night with the recluse.

On our sad parting I ask,

Whenever shall we meet again for a brimful bowl of floral tea…

唐·皇甫冉

送陸鴻漸棲霞寺採茶

採茶非採菉

遠遠上層崖

布葉春風暖

盈筐白日斜

舊知山寺路

時宿野人家

借問王孫草

何時泛椀花

Commentary

The harvesting of fine tea is very different from the gathering of garden vegetables. Unlike cultivated greens and kitchen herbs, superior tea plants grow wild among high cliffs, and the climb to them is difficult. In springtime, tea is fostered by sunshine and warm winds. Its leaves, however, are collected in the cool dark hours of the early morning, the baskets filled before dawn.

Lu Yu 陸羽 (ca. 733-804) once traveled to Nanjing where he resided at Qixia Temple, a monastery renowned for its tea gardens. During his brief residency at the monastery, Lu Yu lived in a hermitage where he received Huangfu Ran 皇甫冉 (ca. 714-765), a friend who came to visit with him. On his departure, Huang recalled their farewells in his poem. Taking Lu Yu’s hand, Huangfu Ran wondered when they would meet again and have the pleasure of drinking bowls overflowing with hua 花, the frothy floral essence of tea.

Source

Huangfu Ran 皇甫冉 (ca. 714-765), Song Lu Hongjiang Qixia si caicha 送陸鴻漸棲霞寺採茶 in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Quan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), juan 210.

Miscellaneous Rhymes on Tea

Pi Rixiu of the Tang dynasty

Miscellaneous Rhymes on Tea

Tea Garden

At leisure, seeking Mount Yaoshi.

Finding and entering the tranquil garden.

Cultivating tea and creating the estate,

Planting tea and planning the field.

Water trickles from the stone spring,

Clouds thread the break in the cliff.

Summer just starting,

White flowers brimming with misty rain.

Teaists

Born on Mount Guzhu,

Now old among the stony gardens.

We talk only of tea,

Our robes scented with mists and clouds.

The courtyard hidden by the jade green plants;

We remain, despite the threat of wild beasts.

At day’s end, laughing as we return home,

Baskets lightly tied about our waists.

Tea Shoots

Budding, three to five inches;

Growing and fostered by the cliffs.

Dreading the cold, shoots turn red;

Doubting the warmth, buds turn purple.

Round like a polished jade axle,

Fragile like a frozen jade flower.

Each encounter is sparse;

Even the sunny side of the mountain is draped in a distant dream.

Tea Basket

Taking up the bamboo basket at dawn,

Crossing quickly to the tea grove.

Steadily tossing in the russet buds,

Our backs soaked with dew.

We rest near Cloud Spring;

Returning, the basket still hangs in the misty tree.

How rewarding is this life,

Even precious gold is eclipsed.

Tea Hut

Sunlit cliffs cradle the commons;

Voices, playful and lively.

The shed draws water from Red Spring;

Before firing, steam the russet buds.

Husbands pulp the tea, next

Wives mold tea, then rest.

Close the brushwood gate;

Pure fragrance fills the moonlit hills.

Tea Stove

Within the mountains, tea happening:

The stove set in the foothills;

The water boils, the rocks emit steam;

The tinder fired, the pine sap fragrant.

Jade leaves steamed, then gelled;

Green essence heated to a luster.

Wherefore such bitter hardship?

One by one, the creation of unsurpassed fare.

Tea Hearth

Chiselled beneath the Green Cliffs,

Precisely two feet deep.

Plastered simply to the rocks,

Fire does not obstruct the stony veins.

It begins the parching of the golden cakes,

Gradually drying the jade tea.

Fir Woods encompasses nine li,

Facing the mountain side.

Tea Brazier

The town of Longshu has fine artisans

Casting this beautiful form.

Standing compact and solid,

Boiling with a rushing sound.

Shadowed by evening clouds — the hermitage;

Luminated by melting snow — the window of pines.

Now ladling rich tea;

Lore and legend grasp this exceeding purity.

Tea Bowl

The artisans of Xing and Yue

All create bowls

As round as the moon,

As light as the clouds.

The floral froth enthralls the eye,

Fruit fragrant foam cleanses the mouth.

A single glance from beneath the pines;

Master Zhi knew this…

Brewing Tea

Fragrant spring water — like milk,

Boil to form strings of pearls.

When crab eyes spray,

Suddenly fish scales rise.

The sound of rain in the pines;

The foam creates a misty green.

Rain still drips in the mountain…

Wine need not be drunk for a thousand days.

唐 皮日休

茶中雜詠

茶塢

閑尋堯氏山

遂入深深塢

種荈已成園

栽葭寧計畝

石窪泉似掬

岩罅雲如縷

好是夏初時

白花滿煙雨

茶人

生於顧渚山

老在漫石塢

語氣為茶荈

衣香是煙霧

庭從𣟤子遮

果任獳師虜

日晚相笑歸

腰間佩輕簍

茶筍

褎然三五寸

生必依岩洞

寒恐結紅鉛

暖疑銷紫汞

圓如玉軸光

脆似瓊英凍

每為遇之疏

南山掛幽夢

茶籝

筤篣曉攜去

驀個山桑塢

開時送紫茗

負處沾清露

歇把傍雲泉

歸將掛煙樹

滿此是生涯

黃金何足數

茶舍

陽崖枕白屋

幾口嬉嬉活

棚上汲紅泉

焙前蒸紫蕨

乃翁研茗後

中婦拍茶歇

相向掩柴扉

清香滿山月

茶竈

南山茶事動

竈起岩根傍

水煮石發氣

薪然杉脂香

青瓊蒸後凝

綠髓炊來光

如何重辛苦

一一輸膏粱

茶焙

鑿彼碧岩下

恰應深二尺

泥易帶雲根

燒難礙石脈

初能燥金餅

漸見幹瓊液

九裏共杉林

相望在山側

茶鼎

龍舒有良匠

鑄此佳樣成

立作菌蠢勢

煎為潺湲聲

草堂暮雲陰

松窗殘雪明

此時勺複茗

野語知逾清

茶甌

邢客與越人

皆能造茲器

圓似月魂墮

輕如雲魄起

棗花勢旋眼

蘋沫香沾齒

松下時一看

支公亦如此

煮茶

香泉一合乳

煎作連珠沸

時看蟹目濺

乍見魚鱗起

聲疑松帶雨

餑恐生煙翠

尚把瀝中山

必無千日醉

Source

Pi Rixiu 皮日休 (834-883 A.D.), “Chazhong zayong 茶中雜詠 (Miscellaneous Poems on Tea) in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Quan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 611, nos. 47-56.

Notes

The ten poems by Pi Rixiu were responded to by his friend Lu Guimeng陸龜蒙 (?-881), “Fenghe Ximei chaju shiyong 奉和襲美茶具十詠 (Offering Matching Rhymes to Pi Rixiu’s Ten Songs on Tea).” For a translation of the responding themes and poems by Lu Guimeng, see

The Huzhou Lei Tea Jar

An ancient jar is the earliest object identified with certainty as tea ware. The ceramic was found in a third century tomb where it was offered as funerary goods, that is to say, objects of daily use placed in the burial chamber as sacrifice to the dead. The size, shape, and features of the pottery reveal that it functioned as a storage container, while its inscription verifies that the jar was once designed to hold tea.

Made of glazed stoneware, the vessel is of fair size and well-proportioned. Generally globular in shape, the body narrows from a broad waist to a flat foot and bears a stamped geometric design known as leiwen or thunder pattern. The mouth opens from a short neck, a rounded ring that surmounts a shoulder marked by a double string band and four small lugs. The glaze is a mottled greenish brown color and covers the vessel evenly from the neck to a few broad lappets below the waist.

Under the glaze on the upper shoulder – in the space between the neck ring and the string décor – the jar bears an inscription: the character cha 茶 or tea incised neatly in clerical script. Created with a pointed stylus, the character is a combination of four straight and angled lines and four dots, a simplified rendering in eight strokes of the nine-stroke character cha 茶, meaning tea.

The jar was excavated on April 19, 1990 by the Huzhou Museum from an old tomb discovered at Luojiabang Village, Biannan Township, a site two miles southwest of Mount Wen and just west of Huzhou, Zhejiang. The unoccupied burial chamber was built of brick in the manner of the late Han dynasty and contained other well-made ceramic wares, most notably an animal-shaped ewer, a bird-headed tripod vessel, and a four-lugged jar. The styles of the architecture and the pottery indicate an age spanning from the end of the Eastern Han (25-220) to the Three Kingdoms period (220-280), circa third century of the Common Era.

Described as the archaic vessel type known as lei 罍, the jar measures 33.7 centimeters high and 36.3 centimeters wide with diameters of the mouth and base at 15.5 and 15.5 centimeters, respectively. According to speculation, the ceramic was made at the early pottery kilns of Deqing located about thirty-five miles south of Huzhou. Alternatively and more likely, the jar was manufactured at the ancient Yue kilns near present Ningbo. Both kilns made early green wares known as celadon.

The lei vessel was fully developed as a lidless storage container in both ceramic and bronze during the Shang dynasty, circa 13th-12th centuries B.C., and remained basically unchanged for millennia to this day. To close, the jar was fitted with a wooden plug, sealed with bamboo sheath and fine thick paper, and by use of the lugs was bound with cord. When sealed, the jar was resistant to air and damp. Aesthetically appealing, technically superb, uniform in shape, lightweight, and capacious, the lei was not only the stock storage container of the ages but also perfect for keeping tea.

For several reasons, the Huzhou lei is important to the art and tradition of tea. Dated to the third century, the jar is the earliest known ware expressly dedicated to tea by its manufacture and inscription. The lei is further evidence of tea in the Han and proof of the early epigraphic development and use of cha 茶 to represent the tea plant and its produce, the character recognizable even in a highly stylized and abbreviated form. Both the celadon jar and the tea it was intended to store were likely made near Huzhou, a region that formerly was known as Wucheng. Thus, the celebrated affinity of tea for celadon may be traced from at least the late Han and the Three Kingdoms period. According to the Record of Wuxing by Shan Qianzhi (died ca. 454), the marquisate of Wucheng produced a tribute tea from the imperial estates on Mount Wen in the third century, precisely contemporaneous with the Huzhou lei.

Figures

Lei Jar, 3rd century

China: Eastern Han dynasty-Three Kingdoms period

Ceramic: stoneware with applied glaze

Four lugs, stamped décor, inscribed cha 茶

H: 33.7 cm. W: 36.3 cm.; diameter: mouth 15.5 cm.; base 15.5 cm.

Huzhou Museum

Excavated from the brick tomb M1:1 at Luojiabang Village, Biannan Township, Huzhou, Zhejiang, April 19, 1990. See Zhang Bo 張柏, Zhongguo chutu ciqi quangji 中國出土瓷器全集 (Collected Ceramic Wares Excavated in China) (Beijing: Kexue chuban she, 2008), p. 26.

Tea and the Materia Medica of Tao Hongjing

Tao Hongjing of the Liang dynasty

Baiying and Kucai

Baiying 白英, white flower. Its taste is sweet, its medicinal character is cold, and it is not poisonous. It cures chills and fever, the eight jaundices, indigestion and thirst, restores equilibrium and benefits qi 氣, the life force. Prolonged use lightens the body and extends life. One name for it is gucai 谷菜, herb of the valley; another name is baicao 白草, white herb. It is produced in the mountains and valleys of Yizhou. In spring season, pick the leaves; in summer, pick the stems; in autumn, pick the flowers, and in winter, pick the roots. The various prescriptions do not prescribe it, for it is only a food staple cooked in water for people to drink. It only grows in mountains and valleys…there is also baicao 白草, white herb, the leaves make soup to drink to relieve fatigue; however, the roots and flowers are not used. Only Yizhou has kucai 苦菜, a beverage drunk by the natives that promotes health and prevents disease. This is undoubtedly the case.

梁 陶弘景

本草經集注

卷第三

白英

味甘寒無毒

主治寒熱八疸消渴補中益氣

久服輕身延年

一名谷菜一名白草

生益州山谷

春采葉夏采莖秋采花冬采根

諸方藥不用

此乃有菜生水中人蒸食之

此乃生山谷…

又有白草葉作羹飲甚治勞而不用根花

益州乃有苦菜土人專食之皆充健無病疑或是此

Herb category of medicinals

Fruit, herbs, rice, and grains: nominal drugs of no practical application

Kucai 苦菜, bitter herb tea

Superior grade

Its taste is bitter, its medicinal character is cold, and it is not poisonous. It cures the five visceral organs and diseases, relieves gastric obstructions caused by eating grain, alleviates indigestion, intestinal distress, thirst, fever, and ulcers of the skin. Prolonged use calms the heart, benefits qi 氣 – the life force – quickens perception, lessens sleep, lightens the body, delays old age, dispels cold and hunger, and stays the decline of talent and the sublime nature. One name is tuku 荼苦; one, is xuan 選; and another, is youdong 遊冬. It grows in the mountains and valleys of Yizhou. It grows in the mountains and hills and along the roads. It lives through winter and does not die. It is picked on the third day of the third lunar month and dried in the shade. This herb is likely what is now known as ming 茗. One name for ming 茗 is tu 荼. It causes sleeplessness. It too does not wither in winter and is doubtless the same as that which grows in Yizhou. Only Yizhou has kucai 苦菜, which as stated is bitter. This herb kucai 苦菜 is already commented on in the entry of the herb baiying 白英, white flower, in the superior category of the first volume. It is written in the Record of Medicines by Master Tong that “the leaves of kucai 苦菜 grow lush in the third lunar month; in the sixth lunar month, flowers follow the growth of leaves; the stems are straight and the flowers, yellow; in the eighth lunar month, the seeds blacken; when the seeds fall, the roots extend their growth; in winter, the plant does not dry up. The present herb ming 茗 truly resembles this herb kucai 苦菜. The ming 茗 teas of Xiyang and Wuchang are comparable to those of Lujiang and Jinxi: they are all excellent. Easterners make only green ming 茗 tea. Ming 茗 tea is always beneficial. Of all beverages, ming 茗 tea compares with the edible leaves of various trees, asparagus sprouts, and china root: all are beneficial, bountiful, and valuable for their cooling properties. Badong has zhentu 真荼 tea, the leaves of which when fired twist and knot; these are made into a drink that causes sleeplessness. Zhentu 真荼 is undoubtedly similar to all these very teas. Now, the brewing of beautiful leaves to make tu 荼 tea compares with the herbal made of large black plums and its cooling effects. Nanfang has gualu mu 瓜蘆木, the wild tea tree, which is similar to ming 茗 tea in bitterness and astringency; the leaves are taken and crumpled into bits, brewed, and the liquor drunk. In consequence, there is sleeplessness all night long; indeed, for wakefulness the salt workers depend only on this drink. Along the breadth of all relationships, tea is of the utmost importance; first serve when guests arrive and add fragrant herbs.”

梁 陶弘景

本草經集注

卷第七

果菜米穀有名無實

菜部藥物

苦菜

上品

味苦寒無毒

主治五臟邪氣厭穀胃痹腸渴熱中疾惡瘡。

久服安心,益氣,聰察,少臥,輕身,耐老,耐饑寒,高氣不老

一名荼苦一名選一名遊冬

生益州川谷生山陵道傍淩冬不死

三月三日采,陰乾。疑此則是今茗

茗一名荼又令人不眠亦淩冬不凋而嫌其只生益州

益州乃有苦菜正是苦爾

上卷上品白英下已注之

《桐君藥錄》雲苦菜葉三月生扶疏六月花從葉出莖直花黃八月實黑實落根複生冬不枯

今茗極似此西陽武昌及盧江晉熙茗皆好東人只作青茗

茗皆有之宜人

凡所飲物有茗及木葉天門冬苗並菝皆益人余物並冷利

又巴東間別有真荼火燔作卷結為飲亦令人不眠恐或者此

世中多煮檀葉及大皂李作荼飲並冷

又南方有瓜蘆木亦似茗至苦澀

取其葉作屑煮飲汁即通夜不眠

煮鹽人唯資此飲爾交廣最所重客來先設乃加以香輩爾

Source

Tao Hongjing 陶弘景 (456-536), comp., “Baiying 白英” and “Kucai 苦菜),” Bencao jing jizhu 本草經集注 (Collected Commentaries to the Materia Medica), juan 3 and 7.

Figure

Artist unknown

Portrait of Tao Hongjing as a Daoist, detail

Yuan dynasty, 14th century

Album leaf: ink and color on paper

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Inscription for the Gentleman of Principle

Sheng Yong of the Ming dynasty

Inscription for the Gentleman of Principle

Shaped like the vault of Heaven and the square of Earth:

Bamboo sheathed metal, bamboo wrapped clay.

Within, a lively fire burns,

Bearing sounds of waves on the river Xiang.

One drop of sweet dew

Cleanses my poetic core.

A pure wind sweeps beneath my sleeves,

Carrying me beyond the realm and into the Void.

明 盛颙

苦節君銘

肖形天地

匪冶匪陶

心存活火

聲帶湘濤

一滴甘露

滌我詩腸

清風兩腋

洞然八荒

Source

Sheng Yong 盛颙 (1418-1492), “Kujie jun ming 苦節君銘 (Inscription for the Gentleman of Principle, 1478)” from Qian Chunnian 錢椿年 (active ca. 1530-1535) and Gu Yuanqing 顧元慶 (1487–1565), Chapu 茶譜 (Treatise on Tea, 1541) in Zhongguo lidai chashu huibian jiaozhu ben 中國歷代茶書匯編校注本 (Annotated Compilation of Tea Books of Dynastic China), Zheng Peikai 鄭培凱 and Zhu Zizhen 朱自振 (1934–present), comps. (Hong Kong: Commercial Press, 2014), p. 181.

Three Encomia on the Ten Perfections of Tea

Wen Zhengming of the Ming dynasty

Three Encomia on the Ten Perfections of Tea

Tea Sprouts

The east wind blows across the russet tea,

In a single night it grows an inch.

A floral mist splits the heavy jade leaves,

Clouds gently congeal their tender fragrance.

The morning harvest fills less than a hand,

Returning in the evening, scolded for upsetting the tea basket.

The leaves, precious as yellow gold;

Transport the proffered tribute before the spring festival.

Brewing

Spring flowers fall, hiding the courtyard,

A gentle wind calms the meditation room.

Tend the fire to boil fresh spring water.

The cold moon floats round and shadowy.

Sleepless, yet ever writing of the worthy,

Faithful to the eternal emotions.

Wandering immortals flit about the brazier,

Effortlessly entering the spirit realm.

Stove

Everywhere nourished by spring rains,

Dark mists conceal distant peaks.

Tea contests Heaven’s ambrosia,

Crimson fire and green pine in harmony.

Purple essence condenses,

Descending among us, fragrant and rich.

Feeling tranquil and refreshed,

Sunset shadows the mountains.

Source

Wen Zhengming 文徵明 (1470-1559), “Chashi tu 茶事圖 (The Art of Tea, 1534),” Shiqu baoji xubian 石渠寶笈續編 (Sequel to the Treasure Coffers of the Stone Moat, 1793), Wang Jie 王杰 (1725–1805) et al., comps. (Taipei: Guoli Gugong bowu yuan, 1971), vol. 2, pp. 1051–1052.

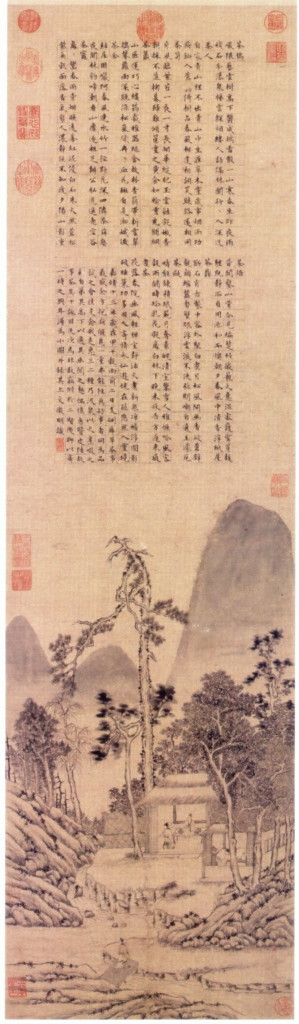

Figure

Wen Zhengming 文徵明 1470–1559)

Chashi tu 茶事圖 (Art of Tea, 1534)

Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Song of Coveting Tea

Wu Kuan of the Ming dynasty

Song of Coveting Tea

I, Elder of the Brew, love tea as I love wine,

Three pints or fifty – there’s no counting.

Beginning in the tea room, there are no unnecessary things:

Just a tea stove and a tea pounder.

Here, there is nothing ever to do but brew tea.

All day long, the tea cup never leaves my lips.

Assisting today’s gathering, a single tea server;

Coming through the door, my guest, a true tea friend.

To express thanks for tea, emulate the poem of Lu Tong;

To brew tea, follow the ode of Huang Jiu.

The Sequel to the Book of Tea, I lend to no one.

The Addenda to the Tea Register, I let slip from the hand:

I will have nothing to do with planting mundane tea.

I know only the few acres of tea garden below this mountain.

Some people merely dream of roaming the tea country,

But I, right here and now, simply do nothing else.

明 吳寬

愛茶歌

湯翁愛茶如愛酒

不數三升幷五斗

先春堂開無長物

只將茶竈連茶臼

堂中無事長煑茶

終日茶杯不離口

當筵侍立惟茶童

入門來謁惟茶友

謝茶有詩學盧仝

煎茶有賦擬黃九

茶經續編不借人

茶譜補遺將脫手

平生種茶不辦租

山下茶園知㡬畞

世人可向茶郷游

此中亦有無何有

Source

Wu Kuan 吳寬 (1435-1504), “Aicha ge 愛茶歌 (Song of Coveting Tea),” Paoweng jia cangji 匏翁家藏集 (Collection of the Paoweng Family Treasures), (Shanghai: Hanfen lou Collection), book 2, juan 4, pp. 7b-8a in Sibu congkan chubian 四部叢刊初編 (Collection of the Four Categories, First Series), Zhang Yuanji 張元濟 (1867-1959), comp. (Shanghai, 1919), vols. 1557-1568.

A Place for Tea

Li Rihua of the Ming dynasty

A Place for Tea

A clean room – with just a broad couch, a ready table, burning incense, a cup of tea – empty of unnecessary things. While sitting in meditation, a pure ethereal force gathers naturally within me. As this chaste and numinous power grows, the foul and turbid effluvium of the world also shifts within and is steadily purged.

明 李日華

潔一室橫榻陳几其中爐香茗甌蕭然不雜他物但獨坐凝想自然有清靈之氣來集我身清靈之氣集則世界惡濁之氣亦徙此中漸漸消去

Source

Li Rihua 李日華 (1565-1635), Liuyan zhai sanbi 六研齋三筆 (Copious Notes from the Studio of Six Pursuits), juan 4, pp. 5b-6a, especially 6a in “Zajia lei 雜家類 (Miscellaneous Treatises),” “Zibu 子部 (Masters and Philosophers),” Qinding Siku quanshu 欽定四庫全書 (Complete Collection of the Four Libraries by Imperial Commission), compiled by Ji Yun 紀昀 (1724–1805) et al. (Beijing: Forbidden City, 1798).

Song of Tasting Tea at West Mountain Temple

Liu Yuxi of the Tang dynasty

Song of Tasting Tea at West Mountain Temple

Beyond the temple eaves, the mountain monks have many tea plants.

Spring arrives and the glow of the bamboo draws out new buds.

Like welcoming a guest, rise and smooth the robes to

Pick from all the lush growth the eagle beaks.

In a instant, the firing fills the room with fragrance.

For an elegant service, ply water from Jinsha,

Listen for the sound of rain and pines from the brazier.

White clouds fill the bowl, billowing here now there.

Even from afar, one whiff dispels the drunken night,

Cares are banished clean to the bone.

From sunny cliffs to shady ridges, each has a special quality,

But those cannot compare to this, moss-grown beneath the bamboo.

Yandi sampled flora but knew not this brew;

Tongjun was prescient yet knew not this flavor.

New buds are curled, not even half ever open.

From picking to brewing takes but a moment or so.

The aroma is like the scent of dew-soaked magnolia;

Next to the color of waves, the jade herb is peerless.

The monks say that the beautiful flavor is crucial to reclusion.

Pick, pick the rich, mellow leaves for the honored guest:

Don’t send it home.

Forget the brick well and bronze brazier,

For how can the spring leaves of even Mengshan and Guzhu

Ever survive the rigors of travel?

He who desires to know the pure, refreshing flavor of tea

Must be a man of sleeping clouds and creeping stones.

唐 劉禹錫

西山蘭若試茶歌

山僧後檐茶數叢

春來映竹抽新茸

宛然爲客振衣起

自傍芳叢摘鷹觜

斯須炒成滿室香

便酌砌下金沙水

驟雨鬆聲入鼎來

白雲滿盌花徘徊

悠揚噴鼻宿酲散

清峭徹骨煩襟開

陽崖陰嶺各殊氣

未若竹下莓苔地

炎帝雖嘗未解煎

桐君有籙那知味

新芽連拳半未舒

自摘至煎俄頃餘

木蘭霑露香微似

瑤草臨波色不如

僧言靈味宜幽寂

採採翹英爲嘉客

不辭緘封寄郡齋

甎井銅爐損標格

何況蒙山顧渚春

白泥赤印走風塵

欲知花乳清泠味

須是眠雲跂石人

Source

Liu Yuxi 劉禹錫 (772-842), “Xishan lanre shicha ge 西山蘭若試茶歌 (Song of Tasting Tea at West Mountain Temple, ca. 805) in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Qüan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), juan 356, no. 15.

Comment

First noted by Liu Yuxi circa 805, West Mountain Temple Tea was yet another example of loose leaf produced by a Buddhist monastery during the Tang dynasty. Half a century before, the poet Li Bo famously named Immortal Palm Tea, a loose leaf produced around 752 at the Jade Spring Temple in Jingzhou, modern Danyang, Hubei. The tea at West Mountain Temple was further noteworthy because it was grown amidst bamboo. Moreover, it was the special practice of the monks to serve guests tea that was not only from the monastery’s own garden but also picked, fired, and brewed especially for the occasion.

Liu Yuxi was a high official and a government reformist during the late Tang dynasty. At court, the reformists were opposed by supporters of the crown prince and by palace eunuchs. When the emperor died and the heir apparent ascended the throne in 805, the reformists were demoted and banished to provincial posts. As one of eight noted reformists, Liu Yuxi was sent into exile to become military adjutant at Langzhou, modern Changde, Hunan, where he spent ten years before being recalled to the capital in 815.

While in Langzhou, Liu Yuxi spent time at West Mountain Temple, a Buddhst monastery. The monks greeted visitors with a very special loose leaf tea. Planted in gardens behind the temple, tea was grown among moss and bamboo. When guests arrived, tea was picked from the bushes and immediately brought to the hall to be fired and brewed with Jinsha Spring water right in front of the visitors. The brew was so fresh that Liu Yuxi opined that not even Yandi the Fire Emperor (Shennong the Divine Cultivator) nor the Yellow Emperor’s physician Tongjun had ever tasted such a wonderful tea. He discouraged guests from sending the tea home, for it would suffer from the journey. Indeed, not even the rare teas of Mount Meng in Sichuan and of Huzhou in Zhejiang might survive the trip. Moreover, water and brewing method would not be the same as at the monastery. Liu Yuxi concluded that only a recluse residing at West Mountain Temple could know the true taste of tea.