Chajing, The Book of Tea

Chajing, The Book of Tea

by

Lu Yu (circa 733-804)

An Annotated Translation, Introduction, and Commentary by Steven D. Owyoung

Introduction to the Chajing,

an excerpt from the forthcoming book on the art of tea

The art of tea was one of the great cultural achievements of imperial China. For over two thousand years, from the Han through the Qing dynasties, tea was a priceless tribute offered to the throne and nobility. Ubiquitous, tea was also enjoyed by aristocrats and commoners alike in the markets and towns throughout the empire. Brewed by acclaimed masters in the mansions of the rich, tea became an essential form of etiquette and politesse. Among the intelligentsia, tea was a high art that nurtured literary pursuits and philosophical discourse.

Like all pleasures of the palate, drinking tea focused on the sensual realms of fragrance, color, and flavor. Connoisseurs and tea masters noted and appreciated the myriad qualities and forms of the leaf, conveying their knowledge as arbiters of taste. There were further aspects of tea, especially those that encompassed the preparation and service of the beverage. In time, the making of tea evolved into performance, highlighting technical skills and personal styles, and thereby offering practitioners recreation, entertainment, and artistic expression. Moreover, the art of tea influenced material culture, notably the decorative arts, in the preference of wares for brewing and drinking as well as serving utensils and preparatory equipage. As a communal endeavor, tea was bound by a concern for the proper and congruent relationship between host and guest. Tea fostered artistic activity, intellectual and scholarly exchange, inspiring rhapsodies, poetry, and prose devoted to the leaf. At the highest levels, the art of tea was a portal to philosophical insight and spiritual attainment.

Historically, the rise and spread of tea began in the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–C.E. 220) from at least the second century B.C.E., when the enfeoffed aristocracy enjoyed tea as an herb and beverage and presented the finest leaf to the imperial palace and the emperor. The appreciation of the art of tea as a profound experience of beauty and meaning flourished in the third century and found early expression in the poetry of the Western Jin dynasty (265–316). By the Tang (618–907), the service of tea was a complete artistic experience, a refined attainment enhanced by beautiful works and tasteful surroundings. As an aesthetic pursuit in the eighth century, the art of brewing the leaf corresponded with the growth of the tea industry as an economic and political force.

In tradition, the scholar Lu Yu 陸羽 (circa 733–804) was credited with the rise of tea during the mid-Tang. He vigorously promoted tea culture through his writings and activities for much of his life. In 780, Lu Yu completed and published the Chajing 茶經, the first treatise ever on the plant, leaf, and drink. Known as the Book of Tea, the work set forth the technical and aesthetic elements of tea and transformed them into a formalized and codified system. During his lifetime, Lu Yu became the embodiment of the perfected tea master, and the Chajing profoundly influenced contemporary Tang and later forms of tea.

Until Lu Yu and the Chajing, little was commonly known about tea or the art of tea. The people of tea growing regions beyond the Yangzi had long harvested, processed, and drunk tea, but knowledge of its use as food, remedial, tonic, and drink was bound to the south where for millennia the plant grew and flourished as part of local culture and custom. From the Western Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–C.E. 8) onward, tea was presented as tribute and sent north to the imperial capital and the palace stores, the inventory used in food and drink, the cuisine of the emperor, nobility, and high officials. For centuries afterward, empirical knowledge of tea was a privileged realm, the purview of accomplished masters — aesthetes, monks, chefs, physicians, apothecaries, and alchemists — its mysteries and utility passed from teacher to disciple. Information about the herb and plant was scattered and buried in ancient tomes, and only the few understood its botanical nature or its proper brewing. Fewer still enjoyed tea as a form of connoisseurship and art, and it was the rare figure who pursued tea as an aesthetic quest. With the Chajing, Lu Yu dispelled the air of exclusivity surrounding tea and changed the art from an elite activity into a social custom of universal appeal.

Lu Yu was an authority on every aspect of the tea plant and herb. When he finished the Chajing, the book was the first and most comprehensive, methodical treatment of tea ever written. Introducing tea as a botanical, Lu Yu identified the origins of the tree and the character of its horticulture. He noted the medicinal uses of tea and its herbal potency and described the harvest and manufacture of tea as well as its preparation and service. Lu Yu described and defined the implements and utensils employed in making tea, and he explained the brewing and drinking of the beverage. Moreover, he set forth rules for tea and compiled an anthology of the herb taken from literature and history. In all, the Chajing was an imposing work of scholarship that expanded the intellectual and literary boundaries of the Tang, while faithfully mirroring the chic activities of a gilded age.

Lu Yu considered tea an evocative art, a subtle matter of the hearth and heart. As a tea master, he strove to produce the fullest expression of the leaf – its hue, scent, and flavor:

“The color of tea is xiang 緗, light yellow. Its penetrating fragrance is exceedingly beautiful…Tea that tastes sweet is jia 檟. That which is not sweet but bitter is chuan 荈. Tea that tastes bitter when sipped but sweet when swallowed is cha 茶.”

To create his tea, Lu Yu used a fine powder ground from caked tea. As described in the Chajing, caked tea was a highly processed and expensive form of the leaf. Harvested leaves were first cooked over steam. Pressed to remove excess water, the leaves were then pounded to a pasty pulp, set in molds, and dried over a low charcoal fire. Depending on the design of the mold, the finished tea resembled a delicate wafer or thin cake shaped as a small but perfect round, square, or flower. In the art of tea, it was the task of the tea master to turn the caked tea into a refined beverage of liquor and foam.

As a poet, Lu Yu exalted the sensuousness of the brew:

“Froth is hua 華, the floreate essence of the brew…Hua 花 froth resembles date blossoms floating lightly upon a circular jade pool or green blooming duckweed whirling along the winding bank of a deep pond or layered clouds floating in a fine clear sky. Mo 沫 froth resembles moss floating in tidal sands or chrysanthemum flowers fallen into an ancient ritual bronze…Reaching a boil, the thickened floreate essence of the brew then gathers as froth, white on white like piling snow.”

Lu Yu began preparing tea by arranging the equipage on a table or stand for display; afterwards, he placed each utensil and implement within reach around him. Next, he lit the brazier, placing a live coal in the ash to light a layer of fine charcoal. Then, he filtered spring water into the cauldron to heat. At the open vent of the brazier, he toasted a cake of tea before grinding it with a mill. The ground tea was sifted to a fine powder, and as the cauldron began to boil a measure of salt was added to the water. The tea powder was then poured into the boiling water to froth and foam. A dipper of hot water was next added to lower the liquid to a simmer. Finally, the frothy tea was ladled into bowls and served.

As presented by the master, even a formal tea appeared to be a casual affair. As Lu Yu prepared the brew, he may have engaged his guest with a comment on the source of the charcoal or a mention of the spring from which the water was drawn that morning or a description of the garden where the tea was grown or a remark on the color of the tea bowl. Or he might have said nothing at all, allowing the beauty of the moment to express everything.

Hidden within Lu Yu’s leisurely asides and silent demonstrations was a profound understanding of tea — a formidable physical and mental regime of technique and concentration that directed his spare, unhurried movements as he brewed the herb. Such knowledge and discipline formed the content of the Chajing and provided the fundamental methods and principles for the art of tea.

The most challenging and sophisticated facets of the art of tea were reflected in the Chajing. At its simplest and most basic preparation, tea was the making of a beverage; in its highest and purist form, tea was an ascetic practice concerned with health, longevity, and the search for immortality. The Book of Tea confirmed the ancient history of tea and upheld its poetic and spiritual aspirations. As an aesthetic pursuit, tea possessed a philosophic quality, one especially attuned to the metaphysical concerns of the nature of Being. In the hands of Lu Yu and the masters before him, the art of tea was believed to be an expression of cosmic Harmony and transcendent Truth.

For his teachings in the Book of Tea, Lu Yu adopted the formulaic mode of sectarian texts. He was inspired by scripture and assumed the didactic and admonitory tone of religious writings. He took Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist works as his models and chose the term jing 經, meaning book or scripture, for his title to signify the canonic character of the Chajing 茶經.

The form and content of Daoist writings greatly influenced Lu Yu. He wrote the Book of Tea in three scrolls and ten parts in keeping with the structure of Daoist holy books and monastic manuals, changing the religious themes to the concerns of tea. Daoist scripture was considered celestial and eternal, written by the spirits and enshrined in Heaven. By emulating works of such divine origin and permanence, Lu Yu sought to present the Chajing and the art of tea as inspired, revelatory, and enduring. In further accord with Daoist belief, Lu Yu identified the mystical and alchemical tradition of tea as symbolic of the herb of immortality, the elixir of life.

The Chajing revealed much about Lu Yu and his approach to the art of tea. When describing the selection and use of accouterments, he was meticulous, specifying the precise number and kind of equipage and citing the exact measurements and capacity of each implement. He applied an unusual yet precise knowledge of techniques and materials to the design and making of tea utensils, describing the minutiae of a mold assembly of a bronze brazier in one instance and stipulating in another the use of a certain rattan for making fine paper. A consummate art connoisseur, Lu Yu revealed the aesthetic subtleties of tea and its related arts, weighing the merits of various media and wares according to their physical properties and aesthetic attributes. The art of tea required utensils possessed of meaning, refinement, and beauty. Lu Yu was keenly aware of the appearance of materials, particularly woods, and recommended baskets of fine bamboo polished to a rich luster. For tea bowls, he favored celadon ceramic wares, because their green glazes enhanced the color of tea. Some implements were chosen for their deep ceremonial significance, their distinctive shapes and materials evoking the sacred ritual of the ancient past.

A stickler for form, Lu Yu was dogmatic and insisted that the complete set of twenty-four articles for tea was absolutely indispensable, especially when making tea for the high nobility. Yet, if brewing tea in the wilderness, he conceded that all but the most essential utensils were expendable. Pragmatic and inclusive, Lu Yu allowed for a great range of styles in tea from the ornate and aristocratic to the plain and rustic, and everything else in between.

Lu Yu revealed his insights and explored the aesthetic dimensions of tea in a language that was highly literary and often poetic. Generally, he wrote in a crisp orthodox style characterized by short phrases of pithy prose. Even when composing prosaic descriptions of equipage and implements — his most formal and methodical moments — Lu Yu paraded his knowledge and entertained twists of rhetoric that were engaging and refreshing. Using esoterica gleaned from his linguistic studies and extensive travels, he challenged scholars with odd dialects and diction as well as a liberal sprinkling of exotic synonyms for the names of ordinary utensils.

In style and manner, Lu Yu was by turns loquacious and laconic. He drew on elegiac imagery for his vivid portraits of tea and often lapsed into verse, once swelling lyrically over the semblance of tea to autumnal flowers cast into an archaic bronze. The mundane and miniscule, he often made quite grand and exciting. With theatrical flair, he spun a simple but dramatic and beautiful account of boiling water, a series of slow mesmerizing stages of bubbling fish eyes and strung pearls that culminated in a sea-surge eruption of flying billows and overflowing froth. He criticized connoisseurs and dismissed their preoccupation with the leaf and its myriad forms. On the finer epicurean points of tea, Lu Yu turned silent and covert, cloaking critical aspects in arcane tradition and mystery. More than just a guide to tea, the Chajing provided the first intimate look at the personal style and innermost thoughts of a highly accomplished and imaginative tea master of the middle Tang.

The Chajing made Lu Yu a celebrity. Scholars admired his knowledge and independent thinking and valued his brilliant and often dramatic spirit. Tea merchants were among his most ardent admirers as they watched stock and sales rise with the popularity of tea spurred by his book. Even the throne awarded him rank and offices: Great Supplicator of the Court of Imperial Sacrifices and Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent. But he spurned fame and popularity, and despite the grand titles bestowed on him, he skirted the bonds and perils of palace service, coveting his freedom and declining the official posts. His disdain for wealth and power was illustrated in one of his most famous songs, a lament in which he pined for the simple life of his hometown and his lost youth:

“I do not desire cups of white jade

Nor desire wine vessels of yellow gold.

I do not desire mornings at court

Nor desire evening audiences.

I do have a thousand, ten thousand desires

For the waters of the West River

Flowing just beyond the walls of Jingling.”

Following lifelong habits, Lu Yu remained a wanderer — traveling, staying at hermitages and temples, and visiting tea gardens. He was praised in the poems of his many friends who documented his tea drinking and his tours of tea gardens throughout the south. Lu Yu continued composing scholarly works until his death around 804, but none of his volumes on the connoisseurship of water or history or genealogy ever achieved the fame of his most celebrated work, the Book of Tea. In Lu Yu’s memory, tea merchants commissioned small ceramic figures of him and gave them to favored customers. His encounters in tea became legendary, enhancing his renown as the ultimate tea master and elevating the Chajing to a venerated canon.

Lu Yu and the Book of Tea had a profound impact on the history and culture of China. He brought about the establishment of Tang imperial tea estates that elevated tea as an offering within the palace tribute system and the ancestral rites of the emperor. His preference for green tea bowls prompted the imperial kilns of successive dynasties to produce and perfect verdant wares of celadon. Driven by social fashion and entrepreneurial production, tea burgeoned in the field and marketplace, an economic expansion that led to the taxation of tea and the banking institution of credit transfers known as “flying money.” The wealth and power generated by tea during the latter eighth century caused the corruption and downfall of high ministers as well as periods of political disruption and social unrest. As a distinctive mark of cosmopolitan and continental culture, tea became an international commodity. Presented as gifts at the distant courts of Korea and Japan, tea was treasured as a great rarity, and there clerics and aristocrats practiced the art of tea assiduously, inspiring the transformation of the social and cultural fabrics of both peninsula and archipelago.

The Book of Tea generated studies of the leaf and the art of tea by later masters and connoisseurs. And although the methods and manners of tea changed in time, Lu Yu’s opus magnum was the literary model, the criterion, for all subsequent works on tea, and Lu Yu himself was the epitome of the tea master. From the Tang through the Qing dynasty, down to the present day, despite over a thousand years of change, the Chajing remains, without exception, the most enduring and influential writing on the art of tea.

__________________

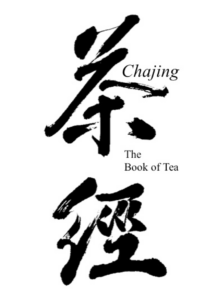

Cover Illustration

Chajing 茶經, calligraphy by Fu Shen 傅申 (Shen C.Y. Fu, 1937–present), noted Chinese art historian, calligrapher, painter, and connoisseur. Former Research Scholar of calligraphy and painting, National Palace Museum, Taipei; Associate Professor, Yale University; Senior Curator of Chinese Art, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; and Professor, Graduate Institute of Art History, National Taiwan University.