Tea in the Warring States Period

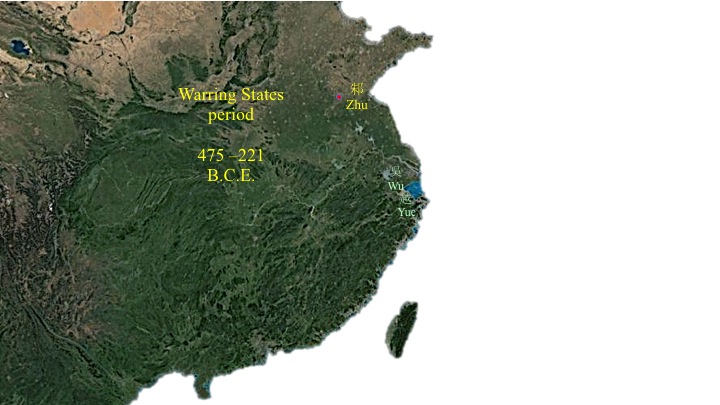

Tea was recently excavated from a royal tomb dating over 2,400 years ago to the late Zhou dynasty (1046-256 B.C.E.) and the period known as the Warring States (475-221 B.C.E.). The discovery was made in Shandong at Zoucheng, the capital of the ancient State of Zhu (11th-5th centuries B.C.E.). The archaeological find confirmed the early use of tea as a funerary offering to the dead and indicated its custom among the living. The archaeological context revealed not only the use of tea but also the likely source of the leaf. Moreover, the use of tea at so northerly a location advanced the geographical range of tea as an item of trade or tribute from tea producing regions south of the Yangzi.

In the eleventh century, during the inaugural years of the Zhou dynasty, the minor State of Zhu was created a vassal and tributary of the major State of Lu. Initially, the ruler of Zhu was ennobled viscount, a hereditary rank, and the state was established just southeast of Qufu, the capital of the State of Lu. Throughout its history, the State of Zhu was harried by its more powerful neighbors and was often forced to move its capital. In the ninth century, the Zhu territory and ruling house were divided to weaken the state. During the Spring and Autumn period, the State of Zhu regained strength. In 659, however, the bordering State of Lu defeated the State of Zhu in battle. In 643, the twelfth ruler of Zhu moved the capital farther southwest to Zoucheng. Over the centuries, nineteen Zhu sovereigns survived the political and military aggression of larger, neighboring states until the State of Zhu and its regnant family were destroyed in the later fifth century.

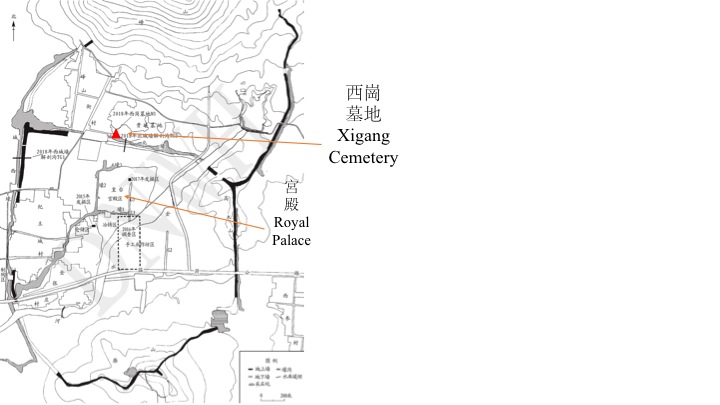

The capital city Zoucheng was strategically sited on the Jinshui River that flowed east to west through the flat, open plain between Mount Yi in the north and Mount Guo in the south. The precinct of the royal palace occupied the north-central axis of the city and was surrounded by a defensive trench and high walls of rammed earth. North of the palace and just beyond the protective ditch lay Xigang, the royal cemetery of the State of Zhu.

In 2018, excavations at Xigang revealed the graves of a Zhu monarch and his queen. Located side by side, each of the tombs was a deep pit constructed of rammed earth in the shape of a square with a wide entry ramp. The tomb of the queen, which was excavated first and designated Tomb M1, was found to have been repeatedly looted by thieves long ago. However, a number of remaining artifacts were discovered, including a pair of jade pendants, a small ring of jade, remnants of gilt and lacquer ware, and a cache of ceramics.

The store of pottery was uncovered on a narrow ledge cut into the south wall of the tomb above the floor of the grave. The earthenware and stoneware pottery were originally placed in a wooden chest that had since rotted away, leaving vessels – jars, large bowls, small cups, a lidded urn – and sherds in a jumble. Also on the ledge, two small stoneware bowls were found overturned, their interiors filled with soil. The earth of one of the bowls contained a dark plant material that was unidentified at the time of excavation but was retained for subsequent examination and testing.

In the past, tea remains from archaeological digs were identified by botanical morphology, the form and structure of the plant. Although the vegetal matter found at Xigang was rotted and blackened as to be unidentifiable by visual means, samples were later subjected to a battery of tests that found the cellular structure of the plant and the abundance of calcium salt crystals matched the genus Camellia. Likewise, the presence of caffeine and theanine identified the plant material as tea.

The remains of tea at Zoucheng were in a small bowl, one of two bowls of similar shape, size, and color that were discovered on the aforementioned ledge above the grave. The two bowls were reported as proto-porcelains, a ceramic type more accurately described as a high-fired porcelaneous stoneware with a greenish feldspathic iron glaze. On the basis of body, glaze, and style, the bowls and the other green-glazed stoneware in the cache were identified as Yue ware, imports from the distant pottery kilns of the southern states of Wu and Yue in Jiangsu and Zhejiang, the only fifth century sources of such early celadons.

As suggested by the Yue ware and its southern sources, the tea gardens of Jiangsu and Zhejiang were also the likely provenance of the leaves in the bowl. Aligned geographically along the eastern seaboard and latticed with transport waterways, the lower reaches of Shandong and the upper stretches of Jiangsu and Zhejiang exchanged tea and ceramics through trade or tribute. Located just south of Zhu, Wu and Yue were nearer sources of tea than the distant tea producing regions of the State of Chu or Sichuan.

It is also noteworthy that nearly all of the ceramics found in Zoucheng Tomb M1 were coupled with vessels of a similar size and shape: two large jars, two pairs of smaller jars, two large bowls, two small bowls, and two small cups; the only exception to pairing was the single lidded urn. Also, the two small bowls appeared distinct from the cache of ceramics by their location, association, and contents. Whereas the other potteries were empty and stored as a group in the wooden case, the two bowls were found separate from the rest, close together, and out on the ledge. Notably, the one bowl contained tea, a comestible that in the context of ritual burial customarily signified ceremonial sacrifice by the living to the dead.

The discoveries in Shandong document not only the earliest evidence to date for the use of tea during historical times but also the earliest use of tea as a funerary offering. Prior to the archaeological finds at Zoucheng, the earliest tea as sacrifice was dated to the second century B.C.E. and excavated from Han Yangling, the mausoleum of the Han emperor Jingdi at Xi’an nearly five hundred miles away to the west in Shaanxi.

Significantly, the concurrence of tea and Yue ware at Zoucheng marked the beginnings of the ancient and enduring tradition that intimately connected the art of tea with the use of celadon, a practice promoted by the Tang tea master Lu Yu in the Book of Tea in which he famously compared the white wares of Xing to the celadons of Yue:

There are those who judge bowls from Xing superior to ones from Yue. This is certainly not so. If Xing is like silver, then Yue is like jade. This is the first way in which Xing cannot compare to Yue. If Xing is like snow, then Yue is like ice. This is the second way in which Xing cannot compare to Yue. Xing ware is white, and thus the color of liquid tea in the bowl looks reddish. Yue ware is celadon, and thus the color of tea appears greenish. This is the third way in which Xing cannot compare to Yue.

References

Lu Guoquan 路國權 et al., “Shandong Zoucheng shi Zhuguo gucheng yizhi 2015 nian fajue jianbao 山東鄒城市邾國故城遺址2015年發掘簡報 (Brief Report on the 2015 Excavation of the Ruins of the Ancient Capital of the State of Zhu, Shandong),” Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) (2018), no. 3, pp. 44-67.

Ma Fangqing 馬方青 et al., “Shandong Zoucheng Zhuguo gucheng yizhi 2021 nian fajue chutu zhiwu da yicun fenxi — jiyi gudai chengshi guanli shijiaozhong de ren yu zhiwu 山東鄒城邾國故城遺址2015年發掘 — 出土植物大遺存分析 (Plant Macro Remains Excavated from the Ancient Capital City Site of the State of Zhu in Zoucheng, Shandong Province in 2015: Humans and Plants in the Perspective of Ancient Urban Management),” Kaogu tansuo 考古探索 (Archaeology Discovery) (4 March 2019), pp. 57–69. Accessed 26 January 2022. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333973022).

Wang Qing 王青et al., “Shandong Zoucheng Zhuguo gucheng yizhi 2015–2018 nian tianye kaogu de zhuyao shouhuo 山東鄒城邾國故城遺址 2015–2018 年 田野考古的主要收獲 (The Primary Findings from the Field Archaeology at the Ruins of the Ancient Capital of the State of Zhu in Zoucheng, Shandong),” Tongnan wenhua 東南文化 (Southeast Culture) (2019), vol. 3, no. 269, pp. 18–24, pls. 1–3.

Jiang Jianrong et al., “The Analysis and Identification of Charred Suspected Tea Remains Unearthed from Warring State Period Tomb,” Scientific Reports (August, 2021), no 11. Accessed 26 January 2022. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353929508).

Lu Guoquan 路國權 et al., “Shandong Zoucheng Zhuguo gucheng Xigang mudi yihao Zhanguo mu chaye yicun fenxi 山東鄒城邾國故城西崗墓地一號戰國墓茶葉遺存分析 (Analysis of Tea Leaf Remains of Number 1 Warring States Tomb at Xigang Cemetery, the Ancient Capital of the State of Zhu, Zoucheng, Shandong), Kaogu yu wenwu 考古與文物 (Archaeology and Cultural Relics)( September, 2021), no. 5, pp. 118-122.