Tea in the Han Dynasty

The story of tea is but one of many historical accounts of plants and their benefit to humankind. Discovered millennia ago by hunters and gatherers of the Stone Age, tea was a source of nourishment and medicine. Over time, its use as a food and drug was refined, and tea became part of the culinary and medical repertoire. Classed as a superior drug, tea was noted as a stimulant and relaxant, simultaneously sharpening concentration while soothing without sedation. At table, tea was consumed as a bitter herb and as greens in soups and stews. Valued as a flavoring and vegetable in cooking, tea was commonly combined with other herbs and fruit. Tea as beverage likely derived from medicinal decoctions, the essence of its buds and leaves extracted and concentrated as a liquor by simmering in hot water or by infusion as a tisane. Tea was prized by commoner and aristocrat alike.

Tea was once native to the remote regions of the south where it was first gathered as a wild plant and then later cultivated as a domesticated crop. Whether as wild or cultivated produce, tea was traded, the demand for the leaf influencing the spread of the tea plant to the lower reaches of the Yangzi. In time, much of the south produced tea of such quality that it was exacted as provincial tribute and sent north to the imperial palace during the Han dynasty.

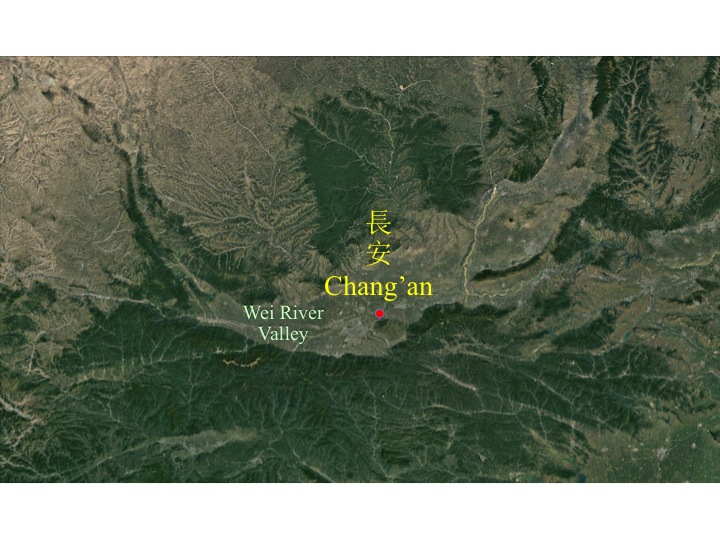

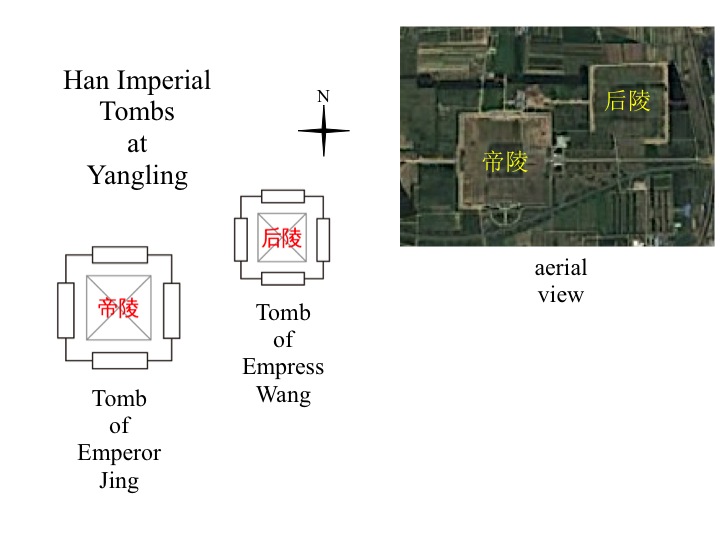

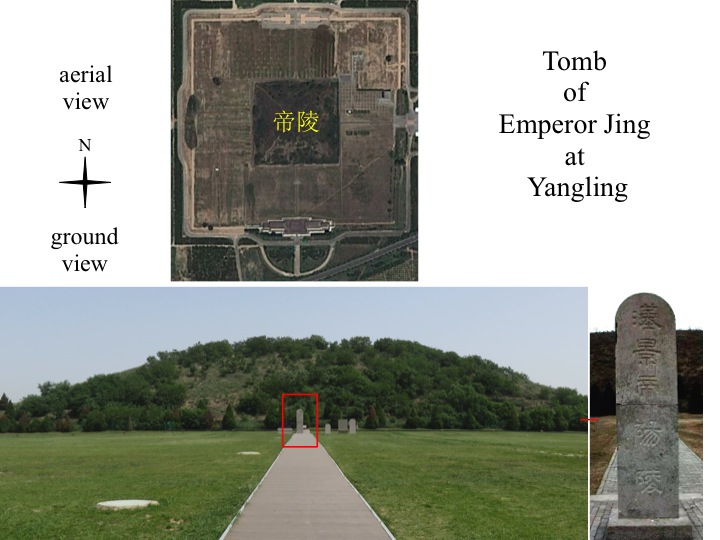

Evidence of tea as tribute was discovered in the Wei River Valley at a Western Han necropolis in the northern suburbs of the ancient capital of Chang’an, present Xi’an, Shaanxi. The site, which is known as the Yangling Mausolea, consists of two pyrimidal mounds, the tombs of Emperor Jing and his empress.

Emperor Jing was the sixth ruler of the Han dynasty; his wife Empress Wang was later buried in an adjacent smaller tomb.

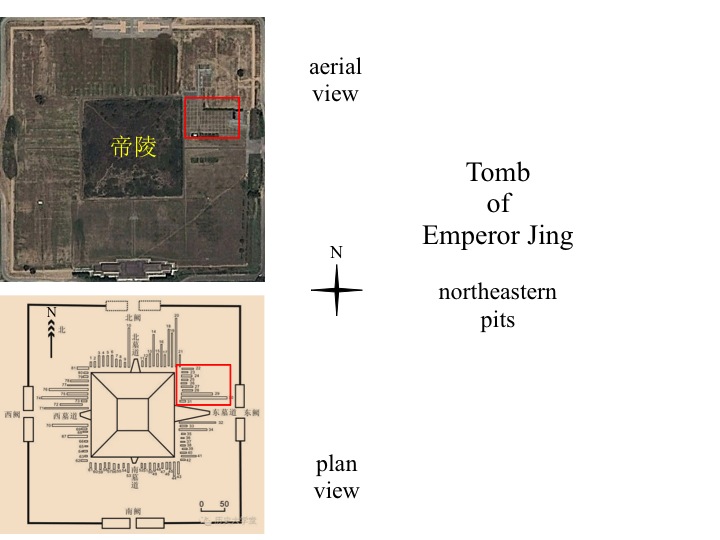

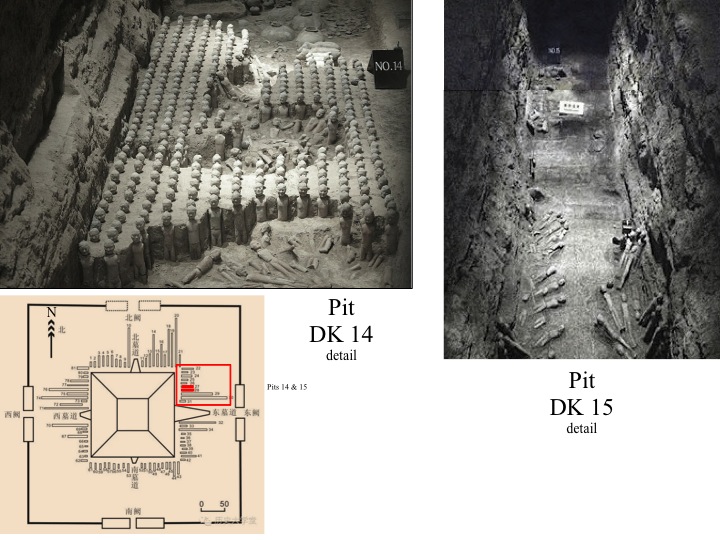

Archaeological investigations of the emperor’s tomb revealed eighty-six outer trenches radiating perpendicular from the four sides of the mound, each long rectangular pit containing funerary goods sacrificed to the dead.

Two pits – designated DK 14 and DK 15 – in the northeast quadrant hold rows of terracotta figures that represent the courtiers, guards, and retainers meant to attend the emperor in the afterlife.

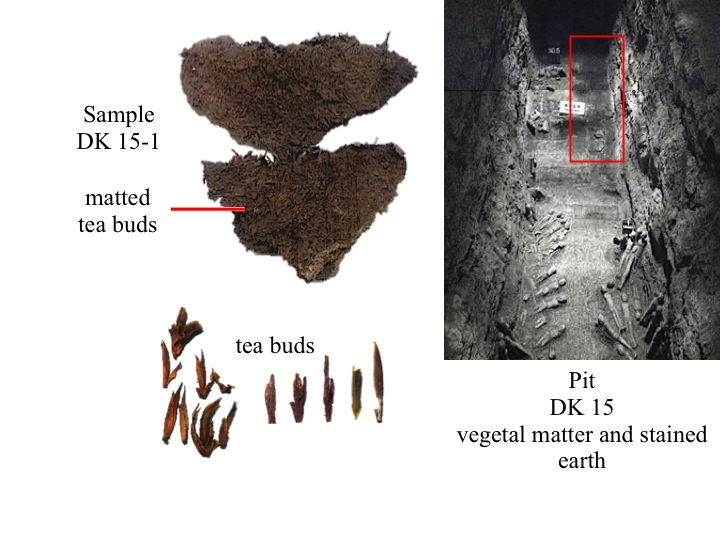

At the eastern end of DK 15, the matted and partially decomposed remnants of organic matter left a large rectangular stain on the earthern floor. Analysis of the fragments showed a mix of seeds, including foxtail millet (Setaria italica), broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), rice (Oryza sativa) and domesticated chenopod (Chenopodium giganteum).

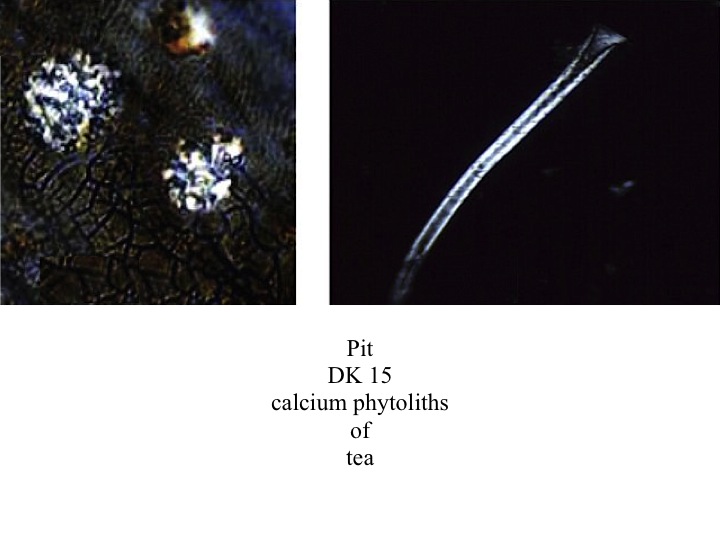

The sample DK 15-1, however, was a mass of plant leaves in a dark brown brick shape: tea. Taxonomic identification of the remnant leaves as tea (Camellia sinensis) was determined by chemical analysis and the examination of plant crystals. Abundant levels of both caffeine and theanine established the leaves as tea, while the ample presence of calcium phytoliths or plant crystals, the types and shapes of which are distinctive to tea, also confirmed the leaves as tea.

The matted remnants of tea revealed that the leaves consisted uniformly of leaf buds, that is to say, only the premium part of the plant was selected and sent to the emperor as tribute. As with all of the other funerary goods in the tomb, the tea was a sacrificial offering to the deceased, and like the grains of millet and rice, probably came from the palace stores.

Sources

Houyuan Lu, Jianping Zhang, Yimin Yang, Xiaoyan Yang, Baiqing Xu, Wuzhan Yang, Tao Tong, Shubo Jin, Caiming Shen, Huiyun Rao, Xingguo Li, Hongliang Lu, Dorian Q. Fuller, Luo Wang, Can Wang, Deke Xu, and Naiqin Wu, “Earliest Tea As Evidence For One Branch Of The Silk Road Across The Tibetan Plateau,” Scientific Reports 6, Article number: 18955 (2016) and Jianping Zhang, Houyuan Lu, and Linpei Huang, “Calciphytoliths (calcium oxalate crystals) analysis for the identification of decayed tea plants (Camellia sinensis L.)” Scientific Reports 4, Article number: 6703 (2014).

Notes

Emperor Jing of the Han (Han Jingdi 漢景帝, né Liu Qi 劉啟, 188-141 B.C.E.), reigned 157-141 B.C.E.

Empress Wang (née Wang Zhi 王娡, 173-126 B.C.E.); consort to Crown Prince Liu Qi, ca. 168 B.C.E.; empress to Emperor Jing, 150 B.C.E.; dowager empress to Emperor Wu, 141 B.C.E.