A Little Tea Book

In the introduction to A Little Tea Book, Sebastian Beckwith and Caroline Paul declare that its contents are devoted to the reader, stating that the small volume truly “is for you.” Take them at their word, and you are amply rewarded by clear and simple explanations of the tea plant and leaf in a series of straightforward narratives on over a dozen aspects of tea, many illustrated by Wendy MacNaughton and her vibrant watercolors.

Throughout the little book, tea is presented as stepping stones that cross many borders, “not only geographic boundaries but political, socioeconomic, cultural, and religious ones as well.” Beckwith describes the art of tea as a process of exploration and invites us all to share in the journey, a tea trek captured in part by his many travel photographs and keen eye for detail, but best of all by his stories of searching the remote regions of Asia for the rarest and most elusive forms of the leaf. In just over one hundred twenty pages or so, Beckwith proves to be a singularly outstanding guide.

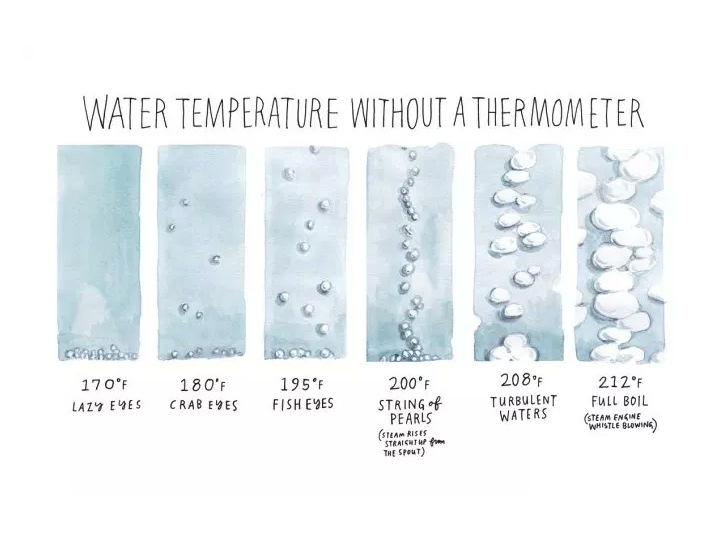

Notable explanations of tea include the distinctions between Camellia sinensis as a plant species, Camellia sinensis sinensis and Camellia sinensis assamica as varietals, as well as tea plants that are bred as cultivars. Beckwith observes the role of the tea green leafhopper (Empoasca (Matsumurasca) onukii Matsuda): the presence and bite of the bug on a leaf produces a defensive response by the plant and the release of chemicals that effect the creation of Oriental Beauty, a wulong tea of exceptional sweetness and aroma. Like the Tang tea master Lu Yu, Beckwith describes water – a much neglected subject in tea – especially the stages of boiling and the look of the hot liquid, all wonderfully illustrated with corresponding temperatures.

Even the scum atop boiled water, which Lu Yu once likened to “dark mica,” is noted and attributed by Beckwith to hard water. Flavors are described as categories: fruit, floral, marine, mineral, sweet, spice, wood, and earth. Vegetal and herbal might qualify as well. Of them all, marine properly describes the fish, seaweed, and kelp flavors of some teas.

Here and there, Beckwith likens tea to fine wine. It is an apt comparison, for the character and quality of bush and vine are influenced by terroir – soil, topography, geology, and climate – the age of the plants, horticulture, harvest, handling, processing, and storage. Indeed, Beckwith goes a step further than analogy and offers several recipes that mix tea and spirits: matcha and shochu, jasmine pearls with vodka, Earl Grey with gin, and sencha and rum.

Perhaps the most important notion in the book is Beckwith’s belief in “rules of thumb rather than rules” regarding the preparation, service, and enjoyment of tea. Rule of thumb is precisely the method used by tea masters from antiquity to the present. The many variables of tea, those changeable factors of water, heat, utensils, and time, require the practice of what the ancients called tasting tea: determining through experimentation how a tea, any tea, is best brewed to exhibit its fullest expression of color, aroma, and flavor.

A Little Tea Book: All the Essentials from Leaf to Cup

Sebastian Beckwith

with Caroline Paul and illustrated by Wendy MacNaughton

New York: Bloomsbury Publishing

2018