Hermitage of the Single Branch

Hermitage of the Single Branch

Dedicated to Brother Anthony of Taizé and Master Hong Keong-hee in great appreciation for their gift of Tea Koreana

In 1823, the Venerable Cho-ui went into seclusion on the slopes of Mount Duryun where he followed the ancient tradition of eremitism, the shutting away of the world to cultivate the self through scholarship and contemplation. For the next forty-three years, Cho-ui took solitary refuge in a place spare and small, built on an earthen platform, in a quiet clearing near dense woods. The dwelling was a rough affair of wooden beams and square posts set on stones coarsely dressed, and of mud plastered walls encircled by a narrow porch, all covered by grass thatch.

He piped clear water through bamboo laid atop stone basins from a trickling spring to feed a pair of small garden ponds and to use for brewing tea. Built and rebuilt as needed, plain and unpainted, the humble abode had several names over the years, including Grass Hermitage, Hermitage of the Way, and Taro Place. Then in 1830, Cho-ui christened the hut Ilji-am 一枝庵, Hermitage of the Single Branch.

The expression “one branch, ilji 一枝” was an ancient literary locution laced with Daoist meaning. Of particular interest to Cho-ui was its allusion to hermitry, the solitary life of the recluse. The idiom appeared around the fourth century B.C., in Free and Easy Wandering, the first part of the Zhuangzi 莊子 written by Master Zhuang Zhou, a follower of the Daoist philosopher Laozi. Master Zhuang recounted an anecdote in which the sage emperor Yao wished to relinquish the throne and its troubles to one Xü You who replied,

“The wren nests in the deep forest on nothing more than a single branch.

The mole drinks from the river taking nothing more than a bellyful.

Return and repair, My Lord. I have no use for the rule of the world!”1

鷦鷯巢於深林不過一枝

偃鼠飲河不過滿腹

歸休乎君予無所用天下為

Refusing the proffered wealth and power of the sovereign, the wise man was content with mere shelter and sustenance. Advising the weary emperor to return to the seat of state and recover equilibrium, the knowing man shunned mundane affairs to further embrace a carefree life.

Later generations looked to the Zhuangzi when remarking on eremitism, and the common wren came to epitomize the blithe yet enlightened existence of the hermit. By the third century A.D., the bird was eulogized by the Jin poet Zhang Hua in the Jiaoliao fu 鷦鷯賦, Ode to the Wren:

翳薈蒙籠 “Obscured in lush and luxuriant thickets,

是焉游集 Right where it plays and gathers.

飛不飄颺 Flying, it does not float.

翔不翕習 Aloft, it is not hurried.

其居易容 Its dwelling easily holds it.

其求易給 Its wants, easily met.

巢林不過一枝 Nesting in the woods, it needs but one branch.

每食不過數粒 Feeding, it takes but a few grains.

棲無所滯 Perching, it does not linger.

游無所盤 Roaming, it does not circle about.

匪陋荊棘 It slights not brambles nor thorns,

匪榮茞蘭 It favors not angelica nor orchids.

動翼而逸 Moving its wings with easy leisure,

投足而安 Skittering about contented;

委命順理 Yielding to fate, it accords with natural patterns

與物無患 Without contending with things.

伊茲禽之無知 For all this bird’s lack of reason,

何處身之似智 Where does it possess such wisdom?

不懷寶以賈害 Disdaining treasure, it avoids buying trouble.

不飾表以招累 Without adornment, it attracts no bother.

靜守約而不矜 Resting, it is simple and frugal, without conceit.

動因循以簡易 Moving, it conforms to the Way, attaining artless ease.

任自然以爲資 Relying on Nature for its means,

無誘慕於世偽 It is not lured by the deceit of the world.”2

Similar sentiment characterized the poetry of reclusion by the Jin contemporary Zuo Si who in the Yongshi bashou 詠史八首, Eight Poems on History, equated the austerity and thrift of the wren with the lofty virtues of the perspicacious man.

俛仰生榮華 “Aspiring to glory and splendor,

咄嗟復彫枯 Tsk, is just carving rotten wood.

飲河期滿腹 Drinking from the river fills the belly,

貴足不願餘 But one can drink only so much.

巢林棲一枝 A forest nest need perch but on a single branch:

可為達士模 Such is the way of the sage.”3

In the ninth century, the hermit poet Hanshan admonished the wavering spirit once tempted by title and office to indulge instead in lofty pursuits, to seek the ready comforts of family, and to be in concert with the rhythms of nature. And then in a harmonious blend of Daoism and Zen, the nested wren became the focal point of meditation:

琴書須自隨 “With zither and book always at hand,

祿位用何為 What use are wealth and rank?

投輦從賢婦 Refuse the imperial carriage, heed the virtuous wife;

巾車有孝兒 A filial son commands the curtained cart.

風吹曝麥地 The wind blows, drying the wheat field;

水溢沃魚池 The water flows, filling the fish pond.

常念鷦鷯鳥 Contemplate the wren bird

安身在一枝 Content on a single branch.”4

Drawn from the long literary use of the wren and its one branch as metaphysical and poetic images, the name Ilji-am 一枝庵 perfectly conveyed Cho-ui’s profound devotion to a life of meditation, simplicity and frugality, a life contained within the four walls of the thatched hut, itself a paradigm of purging the superfluous and hewing to nothing but essentials.

Hermitage of the Single Branch resolved any doubts among his friends that Cho-ui meant to absent himself from them for periods of time. Not that he was without company, for he received students and visitors now and again, though the hermitage had only the barest amenities apart from the hermit’s warm welcome, teachings, and tea. And while usually ensconced within the confines of his modest home, Cho-ui often roamed the countryside and travelled far afield to visit places and friends. Yet, no matter how long he had gone and how dear his reunions, he always returned home to the hut and the eremitic principles for which it stood, ideals that still resonate deep within the eternal hermit heart.

Tea and the Venerable Cho-ui

Cho-ui Uisun5 was a revered Seon Buddhist priest whose knowledge, intellect, and interests distinguished him from other clerics of his generation. He was born in South Jeolla province and lived in Haenam; at fifteen, he became a monk. In addition to Korean, he studied Sanskrit and Chinese to further his understanding of scripture and classical literature as well as the arts. He possessed an aesthetic temperament, mastering tea, music, dance, calligraphy, painting, architecture, and garden design to express an exceptionally vibrant and creative spirit. Moreover, he had a deeply academic bent, writing treatises and verse, seeking out erudite monks and scholars for their learning and companionship, and practicing literati ways, especially tea.

In Cho-ui’s day, tea as regular ceremony and ritual had long been abandoned by temple and monastery, and even at court and palace, tea as rite, courtesy, and beverage dwindled to nothing among the aristocracy and officialdom, then it disappeared altogether from amid the literati and populace at large. For many years, tea survived in various forms and degrees of sophistication amongst a few dedicated monks and learned scholars.

In 1809, at the age of twenty-three, Cho-ui sought out Jeong Yak-yong6 to learn the Book of Changes, Daoism, and Chinese classical poetry. Just the year before, Jeong Yak-yong had moved during his exile from the capital into a place overlooking Gangjin Bay, a quiet house surrounded by tall bamboo and red camellia and by tea shrubs. Feral and wild, the tea grew partly shaded under the open canopy of trees and bamboo on the nearby slopes known locally as Dasan, Tea Mountain. Taking the name from the hills about, Jeong Yak-yong came to be known by the sobriquet Dasan, and his original thatched house was called Chodang, Grass Hall.

Jeong Yak-yong accepted Cho-ui as his student, and the young priest spent several months learning from the older scholar. In addition to daily lessons, the two shared their leisure time together, taking wandering walks to enjoy the scenic views, engaging in the literary form of pure conversation, composing poetry, and drinking tea. Profoundly imbued with these literati practices, Cho-ui observed them for the rest of his life.

As a Seon Buddhist, Cho-ui knew of tea as a medicinal herb used as a meditational aid prepared by monks who he noted “often picked tea late, old leaves and dried them in the sun. Using firewood, they cooked them over a brazier, like boiling vegetable soup. The brew was strong and turbid, reddish in color, the taste extremely bitter and astringent.”7 Under the tutelage of Jeong Yak-yong, Cho-ui learned tea as art, a high aesthetic pursuit and a refined culinary experience.

Later in life, Cho-ui wrote two important works to recover tea for Korean culture. In 1830, he produced the Chasin-jeon 茶神傳, Chronicle of the Spirit of Tea, a guide to the art of tea based on Ming Chinese practices for steeping the leaf. Seven years hence in 1837, he composed the Dongcha-song 東茶頌, Hymn in Praise of Eastern Tea. Then in 1850, Cho-ui sent tea and a revealing poem to a friend:

從來未能洗茶愛 “The desire for tea never washed entirely away;

持歸東土笑目隘 Restoring it to the Eastern Land, I smile and muddle on.

錦纒玉壜解斜封 Unraveling the knots to bare the brocades in the jade jar,

先向知已修檀稅 First to cherished friends do I offer the gift of tea.”8

Despite their disarray, Cho-ui revived the surviving remnants of tea culture, studying the various methods and teas, the assorted “brocades” secreted in the precious “jade jar” of history and literature. Until the end of his days, Cho-ui practiced tea, renewing and personally spreading the long lost custom among the literati and monasteries, profoundly influencing the Korean art of tea for generations thereafter.

Selected Sources

Brother Anthony of Taizé, Hong Kyeong-Hee, and Steven D. Owyoung, translators, Korean Tea Classics by Hanjae Yi Mok and the Venerable Cho-ui (Seoul: Seoul Selection, 2010), pp. 59-65.

Brother Anthony of Taizé and Hong Kyeong-Hee, The Korean Way of Tea (Seoul: Seoul Selection, 2007).

Brother Anthony of Taizé, “Tea in the Early and Later Joseon,” Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch (Seoul: Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, 2011), vol. 86, pp., 119-141, esp. 139.

Young Ho Lee, Ch’oŭi Ŭisun: A Liberal Sŏn Master and an Engaged Artist in Late Chŏson Korea, Fremont: Jain Publishing Company, 2002.

Figures

1.

Ilji-am, Hermitage of the Single Branch

Area approximately 213.5 square feet

Daeheung Temple, Mount Duryun

Haenam, South Jeolla province

South Korea

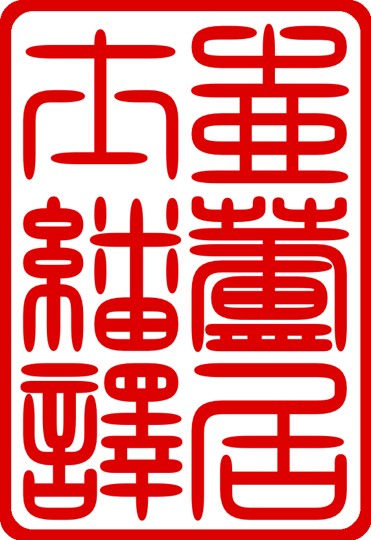

2.

Ilji-am 一枝庵, literally “single branch hermitage”

Calligraphy

Paint on wood plaque under the eaves of

Ilji-am, Hermitage of the Single Branch

Daeheung Temple, Mount Duryun

Haenam, South Jeolla province

South Korea

3.

Artist unknown

Portrait of the Venerable Cho-ui, circa 1866 A.D.

Hanging scroll: ink and color on silk

AmorePacific Museum of Fine Arts

Yongin, Gyeonggi province

South Korea

4.

Artist unknown to author

Portrait of Jeong Yak-yong

Hanging scroll: ink and color on paper

Collection unknown to author

5.

Dasan Chodang, Grass Hall of Master Tea Mountain

Gyul-dong, Mandeok-ri, Doam-myeon

Gangjin, South Jeolla province

South Korea

Notes

1 Exerpted from Zhuang Zhou 莊周 (traditional dates 369-286 B.C.), “Xiaoyao you 逍遙遊 (Free and Easy Wandering),” Zhuangzi 莊子 (Master Zhuang), part 1.4. Cf. Burton Watson, trans., Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings (New York: Columbia University Press, 1964), pp. 26-27.

4 Exerpted from Hanshan 寒山 (flourish ninth century A.D.), Hanshan zi ji 寒山子集 (Collected Works of Master Hanshan). Cf. Red Pine (a.k.a. Bill Porter), The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain (Port Townsend: Cooper Canyon Press, 2000), pp. 42-43 and Robert G. Henricks, ed. The Poetry of Han-shan: A Complete, Annotated Translation of Cold Mountain (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), p. 36, no. 5.

5 Cho-ui Uisun 艸衣意恂 (variously 意洵, 1786-1866 A.D.).

6 Jeong Yak-yong 丁若鏞 (a.k.a. Dasan 茶山, 1763-1836 A.D.).

7 Brother Anthony of Taizé, “Tea in the Early and Later Joseon,” Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch (Seoul: Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, 2011), vol. 86, pp., 138-139.

8 The last lines of a poem by Cho-ui that was “written in rhyme to the poem Sancheon the Daoist wrote thanking me for tea.” Sancheon was Kim Myeong-hui 金命喜 (a.k.a. Sancheon doin 山泉道人, 1788–1857), a high official and calligrapher as well as the younger brother of the noted calligrapher and distinguished official Kim Jeong-hui 金正喜 (a.k.a. Chusa 秋史, 1786-1856 A.D.). Cf. a translation of the whole poem in Young Ho Lee, Ch’oŭi Ŭisun: A Liberal Sŏn Master and an Engaged Artist in Late Chŏson Korea, Fremont: Jain Publishing Company, 2002), pp. 293-294.