Spring of the Instructor: Wenxüe qüan 文學泉

The Spring of the Instructor was once an important source of water in the ancient town of Jingling. Pure and clear, the spring was discovered long ago by a venerated monk, and for hundreds of years thereafter its waters were used to brew tea at the nearby monastery. As the basic medium for making tea, the spring’s sweet water was essential and preferred for its purity, clarity, and taste. According to tradition, the Tang tea master Lu Yü drew water from the spring as a boy. Many sources of fine water were credited to Lu Yü during his lifetime, but the spring at Jingling was plainly identified with his adolescence, giving it precedence above all others in the shaping of his taste and ideas on tea. Lu Yü later used the knowledge he gathered from his early time at the spring to write the Chajing 茶經, the Book of Tea. From the late Tang dynasty through the twentieth century until today, the site of the spring was ornamented with pavilions and halls to commemorate the Book and life of Lu Yü, the Sage of Tea.

The Spring of the Instructor was once an important source of water in the ancient town of Jingling. Pure and clear, the spring was discovered long ago by a venerated monk, and for hundreds of years thereafter its waters were used to brew tea at the nearby monastery. As the basic medium for making tea, the spring’s sweet water was essential and preferred for its purity, clarity, and taste. According to tradition, the Tang tea master Lu Yü drew water from the spring as a boy. Many sources of fine water were credited to Lu Yü during his lifetime, but the spring at Jingling was plainly identified with his adolescence, giving it precedence above all others in the shaping of his taste and ideas on tea. Lu Yü later used the knowledge he gathered from his early time at the spring to write the Chajing 茶經, the Book of Tea. From the late Tang dynasty through the twentieth century until today, the site of the spring was ornamented with pavilions and halls to commemorate the Book and life of Lu Yü, the Sage of Tea.

Lu Yü

Lu Yü 陸羽 was born in 733 but abandoned at the age of two, when he was found near the Longgai si 龍盖寺 temple by Zhiji 智積, the abbot of the Chan Buddhist Monastery of the Hidden Dragon. As a novitiate, Lu Yü did chores for his teacher, including fetching water to make the abbot’s tea. Longgai Temple was built on an island in the middle of Xihu 西湖, West Lake, a fair and abundant body of water and ample for the needs of the monastery. But, brewing fine tea required the fresh water from the spring. According to temple lore, the spring was first excavated by the revered monk-philosopher Zhidun 支遁 in the Jin dynasty. Thus from the fourth century through the Tang, the source was linked to the venerable Zhidun, and the boy Lu Yü likely knew the source as Zhigong jing 支公井, the Well of Master Zhi. Following the late Tang, however, the well was then called Wenxüe qüan 文學泉, Spring of the Instructor, in honor of Lu Yü. How he became known as the Instructor is a curious story, one full of irony and simple courage.

After leaving Jingling, Lu Yü devoted himself solely to the pursuit of scholarship and tea, disdaining office to live an impoverished but lofty life unencumbered by duties, rank, or title. He eventually moved to Huzhou, a town on the southern shore of Lake Tai where he lived until he died around 804. Aloof and reclusive, Lu Yü was nonetheless so well respected that he garnered imperial titles and influential friends despite his solitary nature. In 772, Lu Yü met the new prefect of Huzhou, the great scholar and calligrapher Yan Zhenqing 顏真卿. For five years, the two men collaborated on cultural and building projects, meeting together at literary gatherings and composing poetry at numerous places in and around Huzhou. In 777, Yan Zhenqing was recalled to the capital where he was awarded numerous ministerial posts at court. Yan was promoted to Grand Preceptor to the Heir Apparent in 780, and it was likely at that time when he advised the throne to appoint Lu Yü to the position of Taizi wenxüe 太子文學, Instructor to the Heir Apparent. But in defiance of the imperial order, Lu Yü boldly declined the office, refusing the emperor and staying true to his eremitic character. The audacious move made Lu Yü all the more esteemed among his admirers, and for the rest of his life he was known as Wenxüe 文學, the title that later inspired the rechristening of the spring at Jingling as the Spring of the Instructor.

After leaving Jingling, Lu Yü devoted himself solely to the pursuit of scholarship and tea, disdaining office to live an impoverished but lofty life unencumbered by duties, rank, or title. He eventually moved to Huzhou, a town on the southern shore of Lake Tai where he lived until he died around 804. Aloof and reclusive, Lu Yü was nonetheless so well respected that he garnered imperial titles and influential friends despite his solitary nature. In 772, Lu Yü met the new prefect of Huzhou, the great scholar and calligrapher Yan Zhenqing 顏真卿. For five years, the two men collaborated on cultural and building projects, meeting together at literary gatherings and composing poetry at numerous places in and around Huzhou. In 777, Yan Zhenqing was recalled to the capital where he was awarded numerous ministerial posts at court. Yan was promoted to Grand Preceptor to the Heir Apparent in 780, and it was likely at that time when he advised the throne to appoint Lu Yü to the position of Taizi wenxüe 太子文學, Instructor to the Heir Apparent. But in defiance of the imperial order, Lu Yü boldly declined the office, refusing the emperor and staying true to his eremitic character. The audacious move made Lu Yü all the more esteemed among his admirers, and for the rest of his life he was known as Wenxüe 文學, the title that later inspired the rechristening of the spring at Jingling as the Spring of the Instructor.

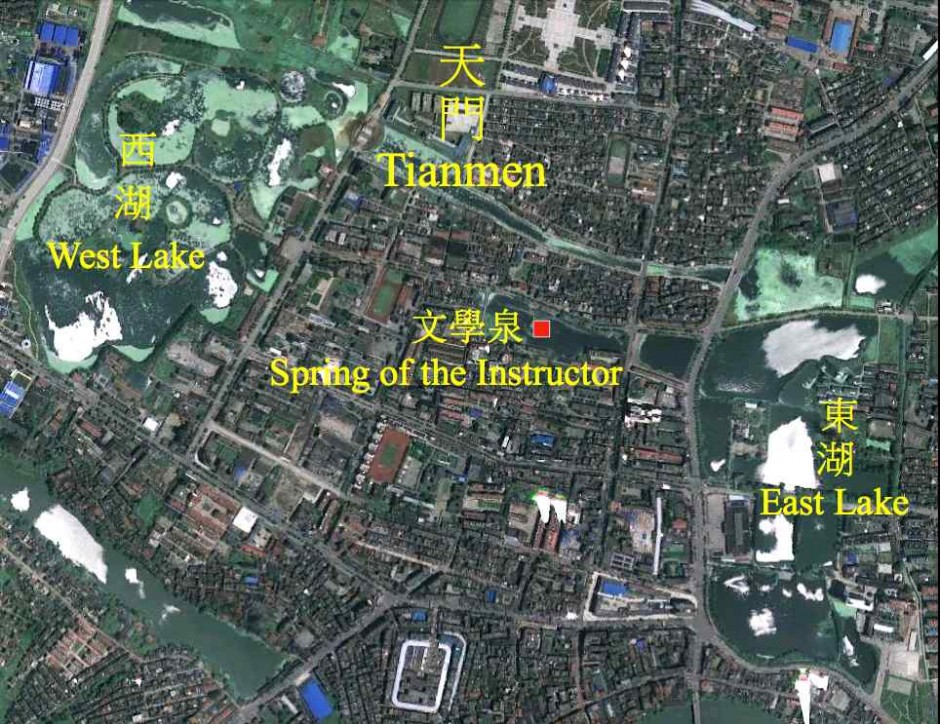

Wenxüe qüan 文學泉, Spring of the Instructor, was originally located just beyond the north gate of the defensive moat and walls that surrounded old Jingling. Today, the spring sits on an island in the middle of Guanchi 官池, the Pond of the Official, a small lagoon that stretches east and west along Wenxüe qüan Road 文學泉路 between West and East lakes. A zigzag bridge crosses over the pond from shore to island.

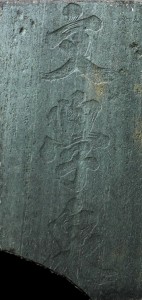

The wellhead is octagonal and comprised of a divided capstone pierced by three holes. Because of its resemblance to the written character pin 品, the well was known by the literary name Pinzi qüan 品字泉, the Pin Character Spring. Among townsfolk, the source was commonly called the Well of Three Eyes, Sanyan jing 三眼井. By the late ninth century, however, the source was referred to as Luzi jing 陸子井, the Well of Master Lu, as well as Spring of the Instructor. Over time, the spring was disused and forgotten.

The wellhead is octagonal and comprised of a divided capstone pierced by three holes. Because of its resemblance to the written character pin 品, the well was known by the literary name Pinzi qüan 品字泉, the Pin Character Spring. Among townsfolk, the source was commonly called the Well of Three Eyes, Sanyan jing 三眼井. By the late ninth century, however, the source was referred to as Luzi jing 陸子井, the Well of Master Lu, as well as Spring of the Instructor. Over time, the spring was disused and forgotten.

History

In 1540, the Ming official Ke Qiao 柯喬 searched everywhere for the spring, but finding no trace of it he built instead a pavilion and a brick lined well at the old monastery, Hidden Dragon Temple. In 1559, the magistrate Qiu Yi 丘宜 ordered the reconstruction of Jingling defenses and found an old well just outside the north gate at the northwest corner of the old town wall. The well was about nine feet across and over a hundred feet deep and contained a broken stele incised with the characters Zhigong 支公, an engraving that referred to the fourth century monk Zhidun. The rediscovery of the spring sparked a celebration of the site for the next five hundred years.

In 1726, the town of Jingling 竟陵 was renamed Tianmen 天門 in deference to the imperial site Jingling 景陵, the mausoleum of the Kangxi emperor. In ancient times, Jingling grew up between the lakes Xihu 西湖 and Donghu 東胡 on the west and east sides of town. Jingling 竟陵 literally means “end of hills,” that is to say, a flat plain with no hills at all that extends eastward about sixty-five miles to the city of Wuhan 武漢 in Hubei province 湖北省. In the Qing dynasty, the name changed from Jingling to Tianmen 天門 after the Tianmen Mountain range 天門山 to the northwest of the town. To the south of town, the Tianmen River 天門河 flows east to join the tributaries of the Yangzi at Wuhan.

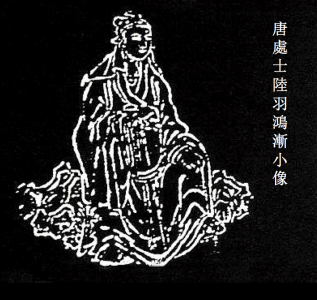

In 1768, the Qing official Ma Shiwei 馬士偉 built a pavilion on the site during which a stele was found engraved with the characters Wenxüe 文學 or Instructor which alluded to Lu Yü. Also found was a wellhead of three holes below which flowed the spring. In 1782, the Hanbi tang 涵碧堂 or Hall of Jade Green Waters was constructed, and in the following year pavilions named Deyüe lou 得月樓, Catching the Moon, and Wenxüe qüan ge 文學泉閣, Spring of the Instructor Hall, were built. In 1783, the official Chen Dawen 陳大文ordered carved two stelae which were installed within the pavilion: one entitled Lu Yü xiang bei ji 陸羽像碑記 contained a posthumous portrait of Lu Yü that is known as Tang Chushi Lu Yü Hongjian xiaoxiang 唐處士陸羽鴻漸小像; the second stone was engraved Wenxüe qüan 文學泉 and carved on the reverse with Pincha zhenji 品茶真跡, Genuine Traces of the Connoisseurship of Tea. In 1939, the Qing buildings were destroyed during the Japanese invasion. In 1957, a visit by Premier Zhou Enlai 周恩來 prompted restoration of the site. In 1961, the site was given the status of a protected cultural treasure but was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. In 1981, the Lu Yü Pavilion 陸羽亭 was constructed, and in 2003 the Hall of Jade Green Waters 涵碧堂 was built.

Tianmen is currently undertaking massive development of Xihu 西湖 and Donghu 東胡 into grand water parks studded with gates, bridges, storied pavilions, halls, causeways, paths, and gardens. Xihu also features Lu Yü gongyüan 陸羽公園, a commemorative park on the lake’s western shore comprised of several sites historically associated with Lu Yü: Lu Yü Memorial Hall 陸羽紀念館; Ancient Geese Bridge 古雁橋; Lu Yü Shrine 陸公祠; and Hongjian Storied Pavilion 鴻漸樓 which houses displays and memorials to the tea master’s life and work.

Tianmen is currently undertaking massive development of Xihu 西湖 and Donghu 東胡 into grand water parks studded with gates, bridges, storied pavilions, halls, causeways, paths, and gardens. Xihu also features Lu Yü gongyüan 陸羽公園, a commemorative park on the lake’s western shore comprised of several sites historically associated with Lu Yü: Lu Yü Memorial Hall 陸羽紀念館; Ancient Geese Bridge 古雁橋; Lu Yü Shrine 陸公祠; and Hongjian Storied Pavilion 鴻漸樓 which houses displays and memorials to the tea master’s life and work.

The offices of the China International Tea Culture Institute 中國國際茶文化研究會 and the Lu Yü Tea Classic Research Center 陸羽茶經研究中心 are close by at No. 79, Wenxüe qüan Road 文學泉路. Just east of the Institute and Center are the renovations of the Pond of the Official 官池 and the site of the Spring of the Instructor 文學泉, which are integral parts of the greater Jingling project.