Tsia and Tsiology: A History of the Words

Introduction

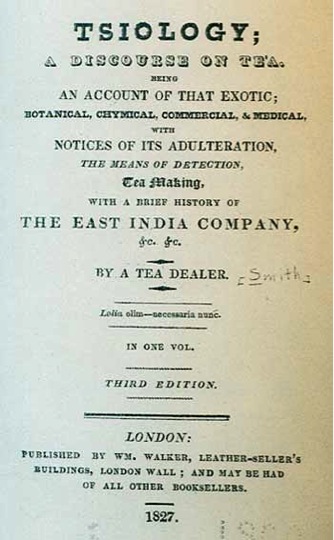

The word tsiology is a nineteenth century expression. Rare and obscure, tsiology was said to mean “a scientific dissertation on tea.”[1] As a term, tsiology was expressly coined in 1826 for a polemical account published that very year in London. In keeping with the expository style of titles of the time, the name of the book ran on at some length: Tsiology: A Discourse on Tea. Being an account of that exotic, botanical, chymical, commercial and medical, with notices of its adulteration, the means of its detection, Tea making, with a brief history of The East India Company, etc. The small, one volume book was written by an English author who anonymously and simply referred to himself as “A Tea Dealer.”[2] In addition to being an exposition on tea, Tsiology was a defense of the East India Company monopoly and a critique of not only escalating government tariffs but also of fraudulent schemes disrupting the domestic tea trade. Tsiology temporarily attracted London readers with its facade of scholarship, the book surviving three editions printed over a year or so.[3] While the book raised several important and timely issues about the British trade, the term tsiology never gained acceptance as an expression of tea, and indeed it all but vanished from literary as well as spoken English.

The word tsiology is a nineteenth century expression. Rare and obscure, tsiology was said to mean “a scientific dissertation on tea.”[1] As a term, tsiology was expressly coined in 1826 for a polemical account published that very year in London. In keeping with the expository style of titles of the time, the name of the book ran on at some length: Tsiology: A Discourse on Tea. Being an account of that exotic, botanical, chymical, commercial and medical, with notices of its adulteration, the means of its detection, Tea making, with a brief history of The East India Company, etc. The small, one volume book was written by an English author who anonymously and simply referred to himself as “A Tea Dealer.”[2] In addition to being an exposition on tea, Tsiology was a defense of the East India Company monopoly and a critique of not only escalating government tariffs but also of fraudulent schemes disrupting the domestic tea trade. Tsiology temporarily attracted London readers with its facade of scholarship, the book surviving three editions printed over a year or so.[3] While the book raised several important and timely issues about the British trade, the term tsiology never gained acceptance as an expression of tea, and indeed it all but vanished from literary as well as spoken English.

Possible reasons for the failure of the word to take hold included the fact that the meaning of tsiology was never explained in the book. Indeed, the word appeared in just the title and not at all in the text. Moreover, tsiology possessed a distinctly affected and questionably foreign character. By way of elucidation, the Oxford English Dictionary defined tsiology in 1933, endowing Tsiology the treatise with a “scientific” guise and labeling tsiology an ad hoc or nonce word; that is to say, a figure of speech created to meet a need that was not expected to recur. The OED noted further that tsiology was derived from the obsolete root word tsia meaning tea.[4]

Cha 茶 and Tsia

Tsia was an early Western attempt to replicate cha, the Chinese and Japanese pronunciation of the written character 茶 for tea.[5] Prior to its introduction from Asia in the seventeenth century, Europe possessed little knowledge of tea and therefore had no word for the plant or leaf. The spelling of the sound cha depended on the practices and peculiarities of the European language employed. Portugal, Spain, France, and Italy variously used cha, ch’a, chá, chia, cia, or cià, while the Netherlands and Germany used t’cha, tsja, tsjaa, or tsia.[6] A further complication arose when Western merchants in Asia learned that cha or tea was also referred to as te, a fact that spurred the European production of words like tay, té, tè, tea, thea, the, and thé. Confusion over the naming of tea endured in Europe for nearly two centuries. In 1712, the German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer observed in Exotic Pleasures that tea had no common Western name that represented the plant, herbal leaf, or drink:

“The Tea, which is by the Japanese call’d Tsjaa, and by the Chinese Théh, hath, as yet, no character of its own, in the learned language of the country, and approved of by the universities; I mean one of those, which, at once give some idea of the very nature of the things express’d by them. Mean while, various other characters have been given to it; some of which merely express the sound of the word, others allude to the virtues and description of the Plant.”[7]

Tsia

The first known instance of tsia for tea was used in A True Description of the Mighty Kingdom of Japan,[8] a book published in 1636 and written for the Dutch East India Company by François Caron who described a multitude of Japanese customs, including the household:

“As for interior décor in the open rooms of their home, there is no furniture, lacquers, boxes, nor cabinets. Furnishings are found in the private rooms, those where there is no access except for close friends and relatives: bowls and containers for tsia [tea], small paintings, calligraphies, swords, such are the primary works of art and curiosities they possess. They must have the most beautiful and most costly, each according to his means.”[9]

Although born in Brussels to French Huguenot parents, François Caron was raised and educated in the Netherlands, joining the Dutch East India Company at age nineteen and shipping out to Japan in 1619 as a cabin boy. He learned Japanese and represented the company factory at Hirado in trade negotiations with the shogunal administration. In his twenty years in Japan, he rose to become chief factor and oversaw the transfer of the mission to Deshima, Nagasaki in 1641. Soon thereafter, while at the Dutch base at Batavia, he was elected a member of the governing council of the East India Company in Asia; he then sailed to Holland as commander of the returning fleet, a prestigious and highly lucrative rank. When he reached Amsterdam, his book on Japan had already been in print for six years.

Caron applied his linguistic skills to the writing of True Description. Utilizing Dutch and Japanese, he originated the Western word tsia for tea; employing French, he then fostered the term thé for tea as well. While describing ceramics used in chanoyu 茶の湯, the Japanese art of tea, he referred to the leaf as thé and indeed treated thé as interchangeable with tsia: “A small box for thé called Naraissiba. A large jar for thé called Stengo.”[10] His book circulated from the Netherlands throughout Europe for over twenty-five years before it was published in English in 1662. By establishing tsia and thé as alternate words for tea early on, François Caron long influenced the Western lexis and the writing of later European works concerning tea.

Tsia next occurred in 1656 and then in 1658, the latter appearance of the word being among the final pages of The Description of the Oriental Travels of the Respectably Well-Born Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo, a travelogue in German that included accounts of the Coromandel Coast, Bengal, Siam, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Bantam, the Philippines, Taiwan, China, and Japan. The author Mandelslo remarked on the Japanese custom of receiving visitors with “Taback und Tsia,” that is to say, tobacco and tea.[11]

Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo was a young German aristocrat at the ducal court of Holstein-Gottorp. In 1633, at age seventeen, he accompanied an official trade mission to Russia and Persia, and while in Isfahan he experienced his first sip of tea. After five years of travel, he parted company with the mission to continue his adventure, making his way through India as far as the port of Surat, all the while noting the “countries, provinces, cities, and islands” of the East Indies. On the voyage home, he stopped in England and crossing the channel made his way to France where he joined a regiment of horse, rising to the rank of cavalry officer. Late in 1644, on his way to Paris for the winter, he fell ill and died of smallpox. According to his will of 1638, he left his writings to Adam Olearius.[12]

Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo was a young German aristocrat at the ducal court of Holstein-Gottorp. In 1633, at age seventeen, he accompanied an official trade mission to Russia and Persia, and while in Isfahan he experienced his first sip of tea. After five years of travel, he parted company with the mission to continue his adventure, making his way through India as far as the port of Surat, all the while noting the “countries, provinces, cities, and islands” of the East Indies. On the voyage home, he stopped in England and crossing the channel made his way to France where he joined a regiment of horse, rising to the rank of cavalry officer. Late in 1644, on his way to Paris for the winter, he fell ill and died of smallpox. According to his will of 1638, he left his writings to Adam Olearius.[12]

Olearius was librarian and mathematician to the duke of Holstein-Gottrop and knew Mandelslo when the younger man was a page at court. As secretary to the same trade mission to Moscow and Isfahan of which Mandelslo was a member, Olearius published a report on the embassy entitled Description of Travels to Moscow and Persia, an account that incorporated Mandelslo’s writings.[13] Printed in 1647, the compilation was translated into Dutch, French, English, and Italian and became known as Olearius’s most famous work. But of all the foreign renditions made during Olearius’s lifetime, the French translation of 1656 by Abraham de Wicquefort enlarged the original book to its greatest extent.

Abraham de Wicquefort was a Dutch scholar whose linguistic and diplomatic talents claimed the patronage of the French and German high aristocracy. During his residence in Paris for the Elector of Brandenburg, he was closely connected to the House of Condé and Cardinal Mazarin, Chief Minister of France for whom he collected rare books. He personally experienced tea in the salons of the French aristocracy and ruling class: tea was habitually drunk as beverage by the chancellor of France Pierre Séguier; and Mazarin used infusions or decoctions of the leaf to treat his gout.[14]

Wicquefort was a gifted translator and created in French a supplemented version of the 1647 report written by Olearius. According to his preface of 1656, Wicquefort augmented Description of Travels to Moscow and Persia with extracts, quotations, and paraphrases from numerous sources, greatly enhancing the original with informative and intriguing bits scattered throughout the work, all with the approval of Olearius.[15]

Tsia and Thé

For his French translation, Wicquefort was partial to the remarks on tea made by François Caron in A True Description of the Mighty Kingdom of Japan and cribbed from the Dutchman’s description on Japanese interior décor[16] as well as the two ceramics Naraissiba and Stengo, which mentioned the herb in the form of either Tsia or Thé. And although he was not credited, Wicquefort likely influenced the posthumous publication of Mandelslo’s notes that Olearius finally produced two years later as an independent book in 1658, wherein extractions from Caron’s work were acknowledged: “Extract aus Relation Francois Caron…Anno 1638 [sic].”[17]

For his French translation, Wicquefort was partial to the remarks on tea made by François Caron in A True Description of the Mighty Kingdom of Japan and cribbed from the Dutchman’s description on Japanese interior décor[16] as well as the two ceramics Naraissiba and Stengo, which mentioned the herb in the form of either Tsia or Thé. And although he was not credited, Wicquefort likely influenced the posthumous publication of Mandelslo’s notes that Olearius finally produced two years later as an independent book in 1658, wherein extractions from Caron’s work were acknowledged: “Extract aus Relation Francois Caron…Anno 1638 [sic].”[17]

With his bibliographic expertise and access to several of the finest private libraries in Europe, Wicquefort was an erudite editor and skillful writer. His reworking of Olearius’s book provided instances of Wicquefort’s knowledge of tea that no doubt included Jesuit writings from Japan and their detailed descriptions of chanoyu.[18] In the science of the period, naturalists began making distinctions between Chinese and Japanese tea: “Chinensibus The, Japonensibus Tsia.”[19] Condensing what he gleaned from his extensive readings, Wicquefort boldly offered a definition of tea based on perceived qualitative differences concerning the thé of China and the tsia of Japan: “As for Tsia, it is a kind of Thé; but the plant is much more delicate, and more highly esteemed than that of Thé.”[20]

In 1662, Abraham de Wicquefort’s French edition of Description of Travels to Moscow and Persia was translated into English by John Davies of Kidwelly who rendered Wicquefort’s further descriptions of Japanese tea:

“Persons of quality keep it very carefully in earthen pots, well stopp’d and luted, that it may not take wind: but the Japanese prepare it quite otherwise then is done in Europe. For, instead of infusing it into warm water, they beat it as small as powder, and take of it as much as will lie on the point of a knife, and put it into a dish of Porcelane or Earth, full of seething water, in which they stir it, till the water be all green, then drink it, as hot as they can endure it. It is excellent good after a debauch, it being certain there is not any thing that allyes the vapours, and settles the stomack better than this herb doth. The pots they make use of about this kind of drink are the most precious of any of their household-stuffe, in as much as it is known, that there have been Tsia pots, which had cost between six and seven thousand pound sterling.”[21]

The “Tsia pots” were, of course, the ceramic tea containers – small caddies and large jars – that Japanese connoisseurs so highly treasured. And unlike Chinese thé, which was steeped as leaf and strained for its liquor, Japanese tsia was ground into a fine powder, used in sparing measures, and whisked in a bowl with hot water to a bright green liquid foam. Here, Wicquefort seemed to suggest that Japanese tsia, powdered and drunk in suspension, had a greater medicinal efficacy,[22] a value reflected, as it were, in the very worth of the artworks used to contain the tea.

Wicquefort’s notion that Japanese tsia was higher in quality than Chinese tea was echoed in the book The Six Voyages of Jean Baptiste Tavernier of 1676. Tavernier was a diamond merchant who traveled to Turkey, Persia, and India, encountering tea in the gem markets and taverns of the East: “They hold in great esteem this herb which is called Thé, which comes from China and Japan, and that from the later [sic] country is the better of the two.”[23] In 1694, the famous Paris apothecary Pierre Pomet wrote in the General History of Drugs that Japanese tea cost considerably more than Chinese by a third. He explained that even though “the Thée of Japan is no different from that of China” its “smaller leaves and its taste and scent are more agreeable. Moreover, because it is usually a brighter and more beautiful light green, the difference in scent, taste, and color greatly increases its price.”[24]

Tsia and Tsja

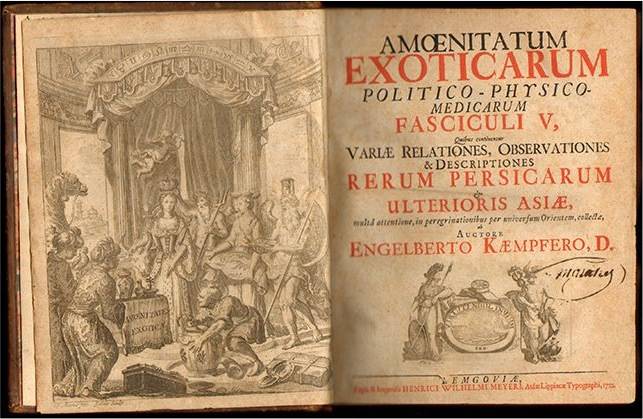

The German naturalist Engelbert Kaempfer also maintained the thé and tsia distinction between Chinese and Japanese teas in his 1712 description of Japan. For his landmark study of the tea plant Exotic Pleasures, he transliterated Japanese tea words and phrases, employing a dozen or more relative terms but adding to the confusion by inventing Thèh and Tsja to represent thé and tsia.[25] Indeed, Kaempfer indiscriminately used not only Tsja for tsia but also Tsjaa for tsia.

Like Adam Olearius before him, Engelbert Kaempfer was secretary to a European embassy to Russia and Persia. And like Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo, Kaempfer continued his travels eastward, eventually sailing to Japan as physician to the Dutch East India Company at Deshima. He spent two years investigating the cultural and botanical aspects of Japan, accompanying the merchant officers on the annual visit to the shogunal capital of Edo. A keen observer of nature and customs, he recorded his findings in Exotic Pleasure, which he published in 1712, seventeen years after his return to Germany.

Like Adam Olearius before him, Engelbert Kaempfer was secretary to a European embassy to Russia and Persia. And like Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo, Kaempfer continued his travels eastward, eventually sailing to Japan as physician to the Dutch East India Company at Deshima. He spent two years investigating the cultural and botanical aspects of Japan, accompanying the merchant officers on the annual visit to the shogunal capital of Edo. A keen observer of nature and customs, he recorded his findings in Exotic Pleasure, which he published in 1712, seventeen years after his return to Germany.

Some decades later, Exotic Pleasures was translated into English in 1727, and Kaempfer’s use of tsia and his inventions of Tsja and Tsjaa were integral to the English version. Employed by the British, tsia, Tsja, and Tsjaa lent a certain weight of scientific authority to later English essays, journals, and books on tea. Tsja and Tsjaa were briefly in vogue and appeared sporadically in a few London publications. In 1772, John Coakley Lettsome wrote The Natural History of the Tea-Tree with Observations on the Medical Qualities of Tea, and Effects of Tea-Drinking in which he used a number of Kaempfer’s words, including Tsjaa (tea), Ficki Tsjaa (ground or powdered tea), Udsi Tsjaa (tea from Uji), Tacke Saki Tsjaa (tea from Takasaki), Tootsjaa (Chinese tea), and Ban Tsjaa 番茶 (coarse tea). In 1808, an anonymous writer adopted the pseudonym Tsjaaphilus to author a series of four articles in The Monthly Magazine of London.[26]

Whomever he was, Tsjaaphilus set the precedent of creating a tea neologism, a term minted to extend the meaning of an existing word, combining Tsjaa with philus to create “lover of tea.” Then in 1826, the anonymous author of A Discourse on Tea likewise generated a new word by joining tsi – the contraction of tsia – with ology to coin tsiology. Today, neither word – tsia nor tsiology – has much currency, and they remain curiosities in the vast lore of tea.

Figures

Anonymous: A Tea Dealer

Tsiology: A Discourse on Tea

London: Wm. Walker, 1827

147 pages

Ink on paper

U.S. National Library of Medicine

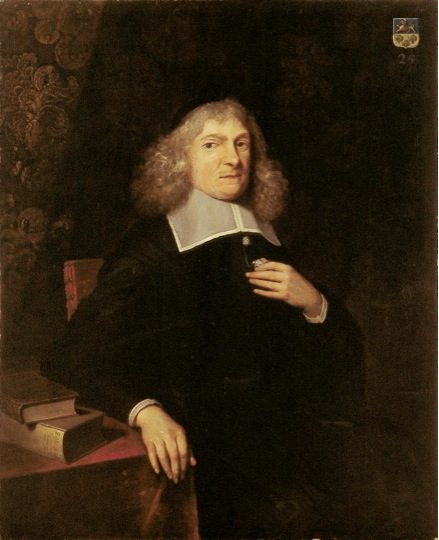

Artist unknown

Portrait of Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo, 17th century

Ink on paper

From Johann Albrechtvon Mandelslo, Voyages Celebres & Remarquables Faits de Perse aux Indes Orientales, par le Sr. Jean-Albert de Mandelslo, contenant une description nouvelle & très-curieuse de l’Indostan, de l’Empire du Grand-Mogol, des iles et presqu’iles de l’Orient, des royaumes de Siam, du Japon, de la Chine, du Congo, &c. … ou` l’on trouve la situation exacte de tous ces Pays & Etats…Mis en ordre & publiez, après la mort de l’Illustre Voyageur, par le Sr. Adam Olearius, Abraham de Wicquefort (Dutch, 1606–1682), trans. (Amsterdam: Michel Charles le Cene, 1727).

Caspar Netscher (Dutch, 1639-1684)

Portrait of Abraham van Wicquefort, 1670

Oil on canvas

Institute Collection Netherlands

Title Page of Exotic Pleasures by Engelbert Kaempfer (German, 1651-1716)

Ink on paper

From Engelberto Kaempfero, Amoenitatum exoticarum politico-physico-medicarum fasciculi v, quibus continentur variae relationes, observationes & descriptiones rerum Persicarum & ulterioris Asiae, multâ attentione, in peregrinationibus per universum Orientum, collecta, ab auctore (Five fascicles of exotic pleasures regarding politics, physics, and medicine, which contain various relations, observations, and descriptions of Persian matters and regions beyond Asia collected through various expeditions through the entire Orient by the author) (Lemgoviae, Typis & impensis H.W. Meyeri, 1712).

Notes

[1] The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 1971), vol. II, p. 3425.

[2] Although omitting his name, the author of Tsiology signed page vi of his preface with an address, “Canton House, No. 1, Gerrard Street, Soho,” Middlesex, London. It is interesting to note that around the same time No. 2, Canton House was occupied by one Lewis Gore Gordon, a tea dealer in partnership with a Charles Ward doing business under the firm of Lewis Gordon and Company. Two years after the publication of Tsiology, Lewis Gore Gordon was a prisoner being sued under the Act for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors in England at a hearing on Saturday, November 1, 1828 at the Court House, in Portugal Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London (The London Gazette [October 10, 1828], no. 18512, p. 1863).

In 2019, Professor George van Driem of the University of Bern commented on the origin and history of the word tsiology in Tales of Tea: “In origin, the book Tsiology is a second-generation plagiarisation of The Tea Purchaser’s Guide of 1785, previously plagiarised by the London Genuine Tea Company in 1820. The term tsiology in this book is derived from the Roman rendering tsia used by Willem Piso in 1658 and Jacob Breyne in 1678 for the Japanese word cha 茶 (ちゃ) ‘tea’. Whether or not tea scientists will choose to style themselves as tsiologists and qualify their scientific investigations as tsiology, and tea philosophers to style themselves as tsiosophers, remains to be seen, but both the coinages are available for those who wish to use them.” Professor van Driem further documented the persons associated with the word tsiology: “The book Tsiology was written anonymously by a ‘Tea Dealer’. The author’s address appears on page vi, however, as ‘Canton House, No. 1, Gerrard Street, Soho’, which at this time was occupied by Lewis Gore Gordon, who together with Charles Ward ran the tea dealership Lewis Gordon and Company. On the 1st of November 1828, two years after the publication of Tsiology, Gordon was sued pursuant to the Act for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors at the court house in Portugal Street. (The London Gazette, Friday, 10 October 1828 [No 18512], p. 1863). Professor van Driem noted, moreover, that “The 1820 plagiarisation was published by the London Genuine Tea Company, founded on the 5th of November 1818 by Frederick Gye and Richard Hughes, who marketed what they described as ‘unadulterated Teas’ at shops on Ludgate Hill, at Charing Cross and in Oxford Street. A fiat of bankruptcy was issued against the two men on the 5th of June 1840 (London Genuine Tea Company. 1820; The London Gazette, Friday, 9 June 1843 [No 20232], p. 1952). See George van Driem, The Tale of Tea: A Comprehensive History of Tea from Prehistoric Times to the Present Day (Leiden: Brill, 2019), ch. 11, p. 760.

[3] Alfred Rehder (American, 1863-1949), The Bradley Bibliography: A Guide to the Literature of the Woody Plants of the World Published Before the Beginning of the Twentieth Century (Riverside Press, 1915), vol. 3, p. 606.

[4] The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 1971), vol. II, p. 3425.

[5] The modern Chinese reading of the ideograph 茶 for tea is romanized in the pinyin romanization system as cha. The obsolete English spellings of tea – tsia, tcha, and chia – attempted to reproduce cha, a sound made of the consonantal ch and the vowel a. The sound ch is a digraph of two characters, c and h, representing a single consonantal sound or phoneme. As a sound, ch is familiar to English speakers as the ch sound in chip. In Chinese, the sound ch may be represented by the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol /t∫/ which in phonology is described as a voiceless postalveolar affricate (or voiceless palato-alveolar affricate or domed postalveolar affricate). In Japanese, the similar sound ch may be represented by the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol /ʨ/ which in phonology is described as a voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate. When the consonantal ch is combined with the vowel a the sound cha is formed: [t∫a] and/or [ʨa], a combination of the ch sound as in church with a long, soft a as in father. In the mouth, the sound is produced by raising the tongue to the hard palate (alveopalatal) with a stop (affricate [t]) immediately followed by forcing the breath through the tongue, palate, and upper front teeth (fricative [∫]), lowering the tongue and jaw, opening the vocal tract, and voicing the low vowel [aː]. For a study of the words for tea, see Victor H. Mair and Erling Hoh, “The Genealogy of Words for Tea,” The True History of Tea (London: Thames and Hudson, 2009), Appendix C, p. 264.

[6] Tsia as well as t’cha, tsja, and tsjaa, are particularly Germanic renditions of the sound cha since German and Dutch inherently lack the consonantal ch in their languages. Many thanks to Professor John T. Kirby for his kind assistance and expertise on this matter.

[7] From the English translation of Engelbert Kaempfer, M.D. (German, 1651-1716), Amoenitatum exoticarum politico-physico-medicarum fasciculi v, quibus continentur variae relationes, observationes & descriptiones rerum Persicarum & ulterioris Asiae, multâ attentione, in peregrinationibus per universum Orientum, collecta, ab auctore Engelberto Kaempfero (Lemgo: Henry Wilhelm Meyer, 1712), fasc. III, pp. 605-631, esp. 608; published in English as The History of Japan together with a Description of the Kingdom of Siam, 1690-1692 (1727), Johann Gaspar Scheuchzer (Swiss, 1702-1729), trans. (Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 1906), vol. 3, p. 218; cf. Engelbert Kaemper, “The History of Japanese Tea,” Exotic Pleasures: Fascicle III, Curious Scientific and Medical Observations, Robert W. Carrubba, trans. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996), p. 144.

[8] François Caron (French-Dutch, 1600-1673) and Joost Schouten (Dutch, ca. 1600-1644), Beschrijvinghe van het Machtigh Coninckryck Japan und Siam (A True Description of the Mighty Kingdoms of Japan and Siam), (Amsterdam, 1636); cf. Charles R. Boxer (English, 1904-2000), ed., A True Description of the Mighty Kingdoms of Japan and Siam [by François Caron and Joost Schouten], Roger Manley (English, ca. 1626-1688), trans., (London: The Argonaut Press, 1935), p. 126.

[9] Translated from French; cf. François Caron (French-Dutch, 1600-1673), Le puissant royaume du Japon: la description de François Caron, 1636, Jacques Proust and Marianne Proust, trans. (Paris: Editions Chandeigne, 2003), p. 136.

[10] A True Description of the Mighty Kingdom of Japan was among the principal European reports concerning the exclusivity and costliness of Japanese tea equipage. François Caron identified two ceramics considered so beautiful that they were given names. The first was “A small box for tea called Narissiba.” The “box” was actually a little covered jar used to hold powered tea, a type of tea caddy in the “square shouldered” Chinese style properly known as katatsuki 肩衝. Together with two other caddies, Narashiba katatsuki 楢芝肩衝 (or variously 楢柴肩衝) was considered one of the “three Meibutsu 名物 (famous things) of the realm.” The second ceramic was “A large jar for tea called Stengo.” The jar was a chatsubo 茶壺 or container for storing tea leaves. Known as Sutego chatsubo 捨て子茶壺 or “the tea jar, Abandoned Child,” the name referred to Lu Yü 陸羽 (ca. 733-804 A.D.), the famous Chinese tea master of the Tang dynasty who was a foundling. Narashiba katatsuki and Sutego chatsubo were part of an extraordinary bequest of art objects given by the retired emperor to his son the emperor. See François Caron (French, 1600-1673), Le puissant royaume du Japon: la description de François Caron, 1636, Jacques Proust and Marianne Proust, trans. (Paris: Editions Chandeigne, 2003), pp. 90 and 255, n. 4 and 5.

[11] Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo (German, 1616-1644), Des hochedelgebornen Johan Albrechts von Mandelslo Morgenländische Reise-Beschreibung. Worinnen zugleich die Gelegenheit und heutiger Zustand etlicher fürnehmen Indianischen Länder, Provincien, Städte und Insulen sampt derer Einwohner Leben, Sitten, Glauben und Handthierung: wie auch die Beschaffenheit der Seefahrt über das Oceanische Meer. Herausgegeben durch Adam Olearium. Mit desselben unterschiedlichen Notis oder Anmerckungen, wie auch mit vielen Kupfferplaten gezieret, Adam Olearius (German, 1603-1671), ed. (Schleswig: Johan Holwein 1658), p. 245.

[12] Adam Olearius (German, 1603-1671), “Preface,” The Voyages & Travels of the Ambassadors Sent by Frederick Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy, and the King of Persia. Begun in the Year M.DC.XXXIII. and Finish’d in M.DC.XXXIX.: Containing a Compleat History of Muscovy, Tartary, Persia, and Other Adjacent Countries. With Several Publick Transactions Reaching Neer the Present Times; in VII. Books. : Whereto are Added The Travels of John Albert de Mandelslo, (a Gentleman Belonging to the Embassy) from Persia, Into the East-Indies. Containing a Particular Description of Indosthan, the Mogul’s Empire, the Oriental Islands, Japan, China, &c. and the Revolutions which Happened in Those Countries, Within These Few Years; in III. Books. : The Whole Work Illustrated with Divers Accurate Mapps, and Figures. Written originally by Adam Olearius, secretary to the embassy. Faithfully rendered into English, by John Davies (English, 1625-1693), of Kidwelly trans. (London: Thomas Dring and John Starkey, 1662), n.p.

[13] Adam Olearius, Offt bergehrte Beschreibung de Newen Orientalischen Reyse So durch Gelegenheit einer Holsteinischen Legation an den König in Persien geschehen : Worinnen Derer Oerter vnd Länder, durch welche die Reise gangen, als fürnemblich Rußland, Tartarien vnd Persien, sampt jhrer Einwohner Natur, Leben vnd Wesen fleissig beschrieben, vnd mit vielen Kupfferstücken, so nach dem Leben gestellet, gezieret ; Item Ein Schreiben des WolEdeln [et]c. Johan Albrecht Von Mandelslo, worinnen dessen OstIndianische Reise über den Oceanum enthalten ; Zusampt eines kurtzen Berichts von jetzigem Zustand des eussersten Orientalischen KönigReiches Tzina, (Schleswig: Bey Jacob zur Glocken, 1647).

[14] William H. Ukers, All About Tea (New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, 1935), vol. 1, p. 34. Cf. Gui Patin (French, 1601-1672), La France au milieu du XVIIIe siecle (1648-1661) d’après la Correspondance de Gui Patin, Armand Brette, ed. (Paris: Librarie Armand Colin 1901), pp. 209-210 and Guy Patin, Lettres de Gui Patin, Paris: J.B. Baillière, 1846), vol. 2, p. 292.

[15] Adam Olearius, “Preface,” Relation du Voyage d’Adam Olearius en Moscovie, Tartarie et Perse, Augmentee en cette nouvelle edition de plus d’un tiers, & particulierement d’une second Partie contenant le voyage de Jean Albert de Mandelslo aux Indes Orientales traduit de l’Allemand par A. de Wicquefort, Resident de Brandebourg, Abraham de Wicquefort (Dutch, 1606–1682), trans. (Paris: Gervais Clovzier, 1656), vol. 1, n.p.

[16] Adam Olearius, “Le Japon,” Relation du Voyage d’Adam Olearius en Moscovie, Tartarie et Perse, Augmentee en cette nouvelle edition de plus d’un tiers, & particulierement d’une second Partie contenant le voyage de Jean Albert de Mandelslo aux Indes Orientales traduit de l’Allemand par A. de Wicquefort, Resident de Brandebourg, Abraham de Wicquefort, trans. (Paris: Jean Du Puis, 1666), vol. 2, bk. 2, pp. 401-449, esp. 432.

[17] Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo, Des hochedelgebornen Johan Albrechts von Mandelslo Morgenländische Reise-Beschreibung. Worinnen zugleich die Gelegenheit und heutiger Zustand etlicher fürnehmen Indianischen Länder, Provincien, Städte und Insulen sampt derer Einwohner Leben, Sitten, Glauben und Handthierung: wie auch die Beschaffenheit der Seefahrt über das Oceanische Meer. Herausgegeben durch Adam Olearium. Mit desselben unterschiedlichen Notis oder Anmerckungen, wie auch mit vielen Kupfferplaten gezieret, Adam Olearius (German, 1603-1671), ed. (Schleswig: Johan Holwein 1658), p. 237. Abraham de Wicquefort did, however, translate Mandelslo’s work; see Johann Albrechtvon Mandelslo, Voyages Celebres & Remarquables Faits de Perse aux Indes Orientales, par le Sr. Jean-Albert de Mandelslo, contenant une description nouvelle & très-curieuse de l’Indostan, de l’Empire du Grand-Mogol, des iles et presqu’iles de l’Orient, des royaumes de Siam, du Japon, de la Chine, du Congo, &c. … ou` l’on trouve la situation exacte de tous ces Pays & Etats…Mis en ordre & publiez, après la mort de l’Illustre Voyageur, par le Sr. Adam Olearius, Abraham de Wicquefort (Dutch, 1606–1682), trans. (Amsterdam: Michel Charles le Cene, 1727).

[18] E.g., Diego de Pantoja, S.J. (Spanish, 1571-1618), Relación de la entrade de algunos padres de la Compania de Iesus en la China, y particulares successos q tuvieron, y de cosas muy notables que vieron en el mismo Regno…Carta del Padre Diego de Pantoja, Religioso de la Compañia de Jesus, para el Padre Luys de Guzman Provincial en la Provincia de Toledo, su fecha en Paquin, corte del Rey de la China, a nueve de Março de mil y seiscientos y dos años (Seville: Alonso Rodriguez Gamarra, 1605); João Rodrigues, S.J. (Portuguese, 1558–1633), Arte del Cha (The Art of Tea) Arte da lingoa (Iapoa Nihon Daibunten) (Nagasaki, 1604-1608) and Arte Breve da lingoa Iapoa (Nihongo Shōbunten, 1620), Historia da Igreja do Japão (History of the Japanese Church, 1620-1633), and This Island of Japon (book 1 of Historia); Alvaro Semedo (Portuguese, 1585-1658), The History of the Great and Renowned Monarchy of China (Rome, 1643); Alexandre de Rhodes, S.J. (French, 1591-1660), Divers Voyages et Missions du P. Alexandre de Rhodes, en la autres Royaumes de l’Orient, etc. (Paris: Cramoisy, 1653); and Martino Martini, S.J. (Italian, 1614-1661), Novus Atlas Sinensis (New Atlas of China) (Vienna, 1653).

[19] Willem Pies (a.k.a. Willem Piso, Dutch, 1611-1678), Jacob de Bondt (a.k.a. Jacob Bontius, Dutch, 1592-1631), and Georg Marggraf (a.k.a. Georg Marcgrave, German, 1610-1648), De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica libri quatuordecim (From India: Things Natural and Medical, Book Fourteen) (Amsterdam: Elzevier, 1658), bk. 7, pp. 87-90, esp. 87. Cf. Sinensium, sive, Tsia Japonensium in Jacobus Breynius (a.k.a. Jacob Breyne, German, 1637-1697), Exoticarum aliarumque minus cognitarum planatrum centuria prima (Centuria or First Century of Exotic Plants, 1678) with an appendix by Willem ten Rhijne (Dutch, 1647-1700).

[20] Adam Olearius, Relation du Voyage d’Adam Olearius en Moscovie, Tartarie et Perse, Augmentee en cette nouvelle edition de plus d’un tiers, & particulierement d’une second Partie contenant le voyage de Jean Albert de Mandelslo aux Indes Orientales traduit de l’Allemand par A. de Wicquefort, Resident de Brandebourg, Abraham de Wicquefort, trans. (Paris: Jean Du Puis, 1666), vol. 2, bk. 2, p. 433.

[21] Quote from Abraham de Wicquefort in Adam Olearius, The Voyages & Travels of the Ambassadors Sent by Frederick Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy, and the King of Persia. Begun in the Year M.DC.XXXIII. and Finish’d in M.DC.XXXIX.: Containing a Compleat History of Muscovy, Tartary, Persia, and Other Adjacent Countries. With Several Publick Transactions Reaching Neer the Present Times; in VII. Books. : Whereto are Added The Travels of John Albert de Mandelslo, (a Gentleman Belonging to the Embassy) from Persia, Into the East-Indies. Containing a Particular Description of Indosthan, the Mogul’s Empire, the Oriental Islands, Japan, China, &c. and the Revolutions which Happened in Those Countries, Within These Few Years; in III. Books. : The Whole Work Illustrated with Divers Accurate Mapps, and Figures. Written originally by Adam Olearius, secretary to the embassy. Faithfully rendered into English, by John Davies, of Kidwelly trans. (London: Thomas Dring and John Starkey, 1662), bk. 2, p. 195.

[22] Compare the remarks of Alexander Rhodes on tea as remedy in Alexandre de Rhodes, S.J. (French, 1591-1660), Divers Voyages et Missions du P. Alexandre de Rhodes, en la autres Royaumes de l Orient, etc. Paris, 1653, p. 49.

[23] Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (French, 1605-1689), Les six voyages de Jean Baptiste Tavernier, Ecuyer Baron d’Aubonne, qu’il a fait en Turquie, en Perse, et aux Indes, pendant l’espace de quarante ans, & par toutes les routes que l’on peut tenir: accompagnez d’observations particulieres sur la qualité, la religion, le gouvernement, les coûtumes & le commerce de chaque païs, avec les figures, le poids, & la valeur des monnoyes qui y ont cours : premiere partie, où n’est parlé que de la Turquie [et] de la Perse (Paris: Gervais Clouzier … et Claude Barbin, 1676), vol. V, p. 257 cited in Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado and Anthony X. Soares Portuguese vocables in Asiatic languages: from the Portuguese original of Monsignor Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, Anthony X. Soares, trans. (New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1988), Volume 1, pp. 93-95, esp. p. 94, n. 1.

[24] Pierre Pomet (French, 1658-1699), Histoire Générale des Drogues (Paris: Jean-Baptiste Loyson & Augustin Pillon, 1694), pp. 143-145; cf. Pierre Pomet, Compleat History of Drugs (1694) (London: 1712), vol. 1, ch. 5, p. 84.

[25] See Hayakawa Isamu 川早勇, “Kenperu no tsukatta nihongo goi ケンペルの使った日本語語彙 (Kaempfer’s Japanese Vocabulary),” Gengo to bunka 言語と文化 (Language and Culture), No.8 (Aichi University, 2003), pp. 119-147.

[26] See Tsjaaphilus, “Letter 1: On the Cultivation of, and Substitutes for, Tea” The Monthly Magazine or British Register (London, August 1, 1808), vol. XXVI, part II, no. 174, pp. 1-3 and his subsequent articles: “Letter 2: On the Tea Plant.” September 1, 1808), pp. 97-98; “Letter 3: On Tea,” October 1, 1808), pp. 201-02; and “Observations on Tea,” December 1, 1808), pp. 414-19.