Characteristics of the Tea Leaf, 1653 A.D.

Martino Martini of the Society of Jesus

Characteristics of the Tea Leaf

There is nothing superior to the famous tea leaf. To satisfy the curious reader and students of botany, here is a brief description:

The small leaf is wholly like that produced by Rhus Coriaria, sumac; however, I am not persuaded that it is of the same species. It is not wild but cultivated, not a tree but a bush that spreads in various branches and twigs, nor does the flower differ much from that of the sumac, except that the white color tends somewhat to yellow. In summer, the flower is fragrant with a light perfume; the green berry follows, and then blackens. To brew the drink Cha, the first tender leaves of spring are sought and gathered, carefully and individually by hand. Then the leaves are warmed a little over a slow fire in an iron pan, and then placed on a matt and rolled by hand, and then fired and rolled again until curled and quite dry. The tea is kept in containers of tin, its essence carefully preserved against all humidity. Even kept after a long while, when cast into boiling water, the leaves uncurl and return to their original greenness. If the tea is of the best quality, the fragrance is sweet and the taste not unpleasant, once used to it, and suffuse with a greenish color. Though many deprecate the virtues and power of this hot beverage, the Chinese drink it often, day and night, and welcome friends with it. Moreover, many varieties of superior tea rise in price to over two gold pieces per pound. Those who drink tea get neither gout nor stones. After eating, it relieves indigestion and aids digestion. Tea may be taken to alleviate inebriation, to refresh and reinvigorate, to relieve hangovers, and it may be used as a diuretic to dispel extraneous fluids. Tea is for those who wish to remain awake and banish sleep and to ward off drowsiness from those who want to study. In China, tea is named after its locale, such as the excellent and famous Sunglo cha. For a fuller description of tea, see the work published in French by Alexander de Rhodes, who describes tea more at length, in the section, Kingdom of Tunking part I, chapter 15.

Cha folium quale.

Folium Cha nominatissimum nusquam alibi, quam hic praestantius est. id in gratiam curiosi lectoris, ac Botanices studiosi brevibus describam:

Foliculum est omnino illi simile, quod rhus coriaria profert, imo illius quandam esse speciem tantum non mihi persuadeo, non tamen sylvestre illud, sed cultum est, non arbor, sed virgultum est, quod in ramulos varios, aut virgulas potius sese diffundit, nec flore admodum differt, nisi quod hujus albedo nonnihil magis in flavedinem declinet; aestate primum florem emittit levi odore fragrantem, sequitur bacca viridior, mox nigricans: pro potione Cha coquenda expetitur folium primum vernum, ac mollius, quod studiose ac sigillatim unum post alterum manu carpunt, mox in ferreo cacabo tenui ac lento igne aliquantulum calefaciunt, deinde supra stoream subtilem ac laevem manibus propellendo involvunt, atque involutum iterum exponunt igni, ac denuo confricant, donec intortum rursus & conglomeratum plane siccum sit: quod servant in vasis plerumque stanneis ab omni humiditate diligentissime & evaporatione custoditum; hoc cum in ebullientem aquam conjicitur etiam post diuturnam asservationem, ad pristinum virorem redit seque expandit, aquam odore suavi, si optimum est, saporeque non ingrato, praesertim ubi adsueveris, ac colore subviridi inficit. Multis hujus calidi potus vires ac virtutem depraedicant Sinae, qui eo noctu & interdiu frequentissime untuntur, hospitesque excipiunt. tanta autem ejus varietas, ac praestantiae discrimen est, ut librae pretium apud ipsos Sinas ab obolo ascendat ad duos plureique aureos: illi potissimum adscribitur, quod Sinae podagram ac calculum nesciant; post cibos sumptum omnem indigestionem ac cruitatem stomachi tollit; maxime enim concoctionem juvat, quin & ab ebriis adhibitum levamen iis, novasque ad potitandum vires affert, adeogue & crapulae omnes molestias levat, siquidem exsiccate & abstergit superfluos humores, ac vigilare cupientibus somniferos vapors expellit, oppressionemque somni studiis vacare volentibus arcet. varia apud Sinas habet nomina; juxta varia loca, eamque, quam obtinet, praestantiam hujus urbis praeclarissimam Sunglocha vocari solet. Pleniorem si quis illius descriptionem desideret, consulat Gallice editum R.P. Alexandrum de Rhodes, qui illud fusius describit, de regno Tunking parte I, cap. 15.

Source

Martino Martini, S.J. (Italian, 1614-1661 A.D.), Novus Atlas Sinensis (New Atlas of China) (Vienna, 1653 A.D.), part 6 of Joan Blaeu (Dutch, 1596-1673 A.D.), Theatrum Orbis Terrarum; sive, Atlas novas (Theater of the World; or New Atlas; a.k.a. Atlas Maior) (Amsterdam: Joan Blaeu, 1662), p. 83.

Compare

Eusèbe Renaudot (French, 1646-1720 A.D.), trans., Ancient accounts of India and China (London: S. Harding, 1733), p. 73; William Crook (English, active ca. 1685 A.D.), The New Relation of the Use and Virtue of Tea printed for W. Crook at the sign of the Green Dragon without Temple Bar, London (1685) cited in Timothy J. Bond, “The Origins of Tea, Cocoa, and Coffee as Beverages,” Teas, Cocoa and Coffee: Plant Secondary Metabolites and Health, lan Crozier, Hiroshi Ashihara, Francisco Tomás-Barbéran, eds. (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), p. 12; Athanasius Kircher, S.J., China Illustrata (1667), Charles D. Van Tuyl, trans. (Muskogee: Indian University Press, 1987), part IV, chap. 6, p. 175; and Bianca Maria Rinaldi, The “Chinese garden in good taste”: Jesuits and Europe’s knowledge of Chinese flora and art of the garden in the 17th and 18th centuries (Munich: Meidenbauer, 2006), pp. 99-100. For the missionary work of Martini, see David E. Mungello, The Forgotten Christians of Hangzhou (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1994), pp. 9-59, passim.

Figure

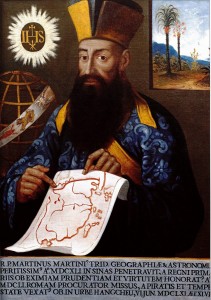

Artist unknown

European, 17th century A.D.

Portrait of Father Martino Martini, 1661 A.D.

oil painting, inscribed:

“The Reverend Father Martino Martini of Trent,

a man of extraordinary skill in geography and

astronomy, who entered China in the year 1641.

Having been honored by the leading men of the realm

because of his exceptional knowledge and virtue,

he was sent to Rome as a [Jesuit] procurator in the

Year 1651. [During the journey,] he was subjected to

hardship by pirates and storms. He died in the city

of Hangzhou on 6 June 1661 at the age of

forty-seven.” (David E. Mungello, trans.)

Museo Provinciale d’Arte

Buonconsiglio Castle, Trento