The Sultaness Head

Thomas Garway and the Marketing of Tea in Seventeenth Century London

Introduction

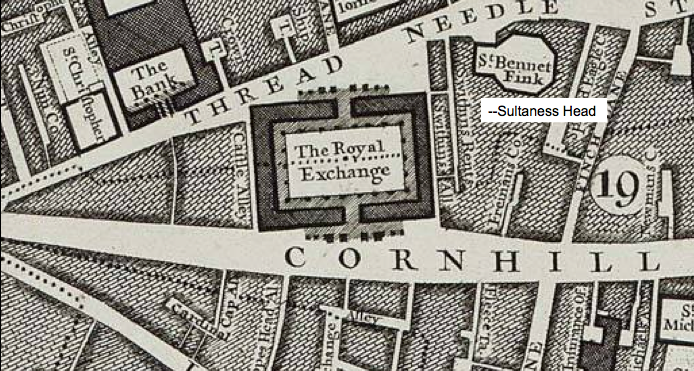

In the history of English tea, the name Thomas Garway was intimately linked with two London coffee houses. The first was the Sultaness Head in Sweetings Rents, and the second, Garraway’s Coffee House in Exchange Alley. The historical treatment of Thomas Garway and his relationship to the Sultaness Head was uneven, and some early writings did not even associate the man with the place. More recent scholarship, principally that of Markman Ellis of the University of London, shows that the proprietor of the Sultaness head was indeed Thomas Garway, the first to offer tea to the English public. The account of Garway is an intriguing tale of tea, one immensely rich in detail and replete with unexpected twists and turns.

Contrary to modern notions, Garway was no aproned shopkeeper but in fact the scion of a great mercantile house, a guildsman, and above all an entrepreneur. Similarly, the Sultaness Head was not merely a coffee house but instead a satellite of commerce and finance in close orbit to the Royal Exchange and the goldsmith banks. Straddling the turbulent periods of the Interregnum and the Restoration, Thomas Garway and the Sultaness Head appeared and prospered in a time of astonishing fortune and extraordinary calamity.

The Sultaness Head

In mid seventeenth century England, tea was known as an exotic drug, a distinctive and efficacious Chinese herb prescribed by doctors and purchased at great expense from the apothecary. Hollanders supplied the precious tea, even during the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the lowlanders profiting from the very lucrative London trade by using ships of English registry. Sea traders and sailors returning to England from the East Indies brought tea to pharmacies and physicians, charging dearly for the small amounts. Men who acquired the taste for tea during their time abroad brought home personal supplies of the leaf, and on occasion tempted and teased family and friends with the novel but costly cordial.

Outside of the habituated few, tea generally remained little known until the brewed leaf was first served to the public in a London coffee house that advertised tea as beverage in the late summer of 1658:

“That Excellent, and by all Physitians approved, China Drink called by the Chineans, Tcha, by other Nations Tay alais [sic] Tee, is sold at the Sultaness-head, a Cophee-house in Sweetings Rents, by the Royal Exchange, London.”[1]

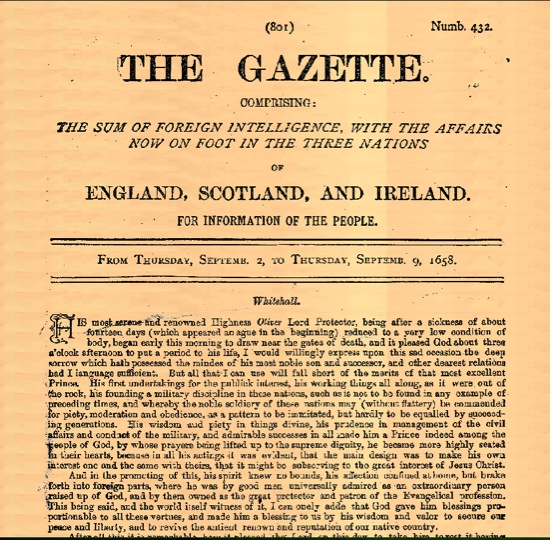

The advertisement appeared on Thursday, September 2nd in The Gazette, a weekly news pamphlet of seven pages: the first four declared the momentous death of the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell,[2] the political and military leader who toppled the English monarchy and established for a brief time a republican Commonwealth. Issued from Whitehall, the official statement was read throughout England, Scotland, and Ireland as well as on the Continent.

Tea surely had no better timing for the announcement of the drink and its pleasures, and neither had the leaf a better venue nor audience. The London readers of The Gazette were especially well informed and keenly focused on the latest intelligence and novelties of the day. Indeed, the proprietor of the Sultaness Head made doubly sure of spreading the news by running the same advertisement a fortnight later in a competing weekly, the Mercurius Politicus, published September 23rd-30th. Printed on the last pages of the news pamphlets, the Sultaness Head trailers were the first public notices of brewed tea for sale as well as among the first advertisements publicizing a particular trade: the coffee house.[3]

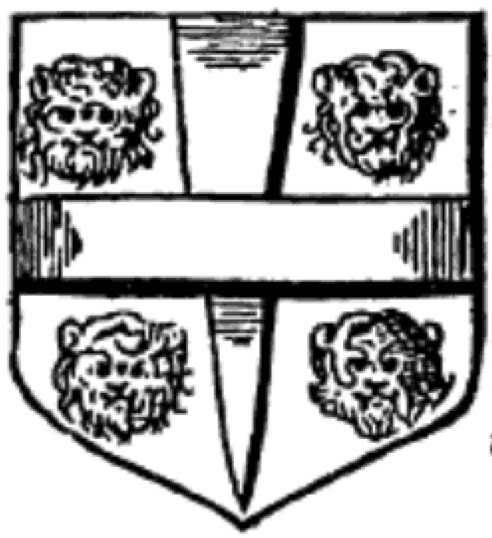

The Sultaness Head was further publicized by its tokens, small coins of copper worth a halfpenny and cast or stamped with inscriptions and images on both sides. Two bought a penny’s worth of coffee. In a time when small coins were scarce, tokens were used by shopkeepers to make change and were redeemable at the place of purchase when proper specie was to be had. The tokens issued by the Sultaness Head bore a female head on the obverse and an armorial shield on the reverse; the inscriptions encircling the motifs read “The Sultaness, A Coffee House” and “Cornhill in Sweetings Rents,” respectively. The coat of arms on the back of the token was key to identifying the proprietor of the Sultaness Head.

Displaying feline bestial heads, the distinctive coat of arms was once described in 1610 as “He beareth, Argent, a Pile surmounted by a Fesse between four Leopards heads, Gules, by the name of Garway.”[4] The crest dated from the fifteenth century and belonged to the master of Ley Woebly Manor in Woebly, Herefordshire, Walter Garway, a man who served Henry VII as Governor of Berwick Castle in Northumberland. The great great grandson of Walter Garway was one Thomas Garway, a seventeenth century English adventurer merchant and the Garway family’s first coffee man. Thomas, who later owned Garraway’s Coffee House, was among the first of few London merchants to capitalize on the exoticism of caffeinated beverages – coffee, chocolate, and tea – the strange but stimulating brews from distant and very foreign lands.

Thomas Garway

Thomas Garway was born in London into an illustrious family of merchants. The Garway patriarchs were mercers and drapers, wealthy members of the formidable livery companies that controlled commercial life along the Thames. From the sixteenth century on, the Garways were farmers of the customs, revenue officials of the crown who provided funds to the Exchequer for the privilege and profit of collecting royal import and export taxes. The founder of the family’s great prosperity was Sir William Garway, Thomas’s granduncle whose ships served Queen Elizabeth I and repelled the Spanish Armada. Generations of Garways were investors and governors in the Virginia, Somers Island, East India, Levant, Greenland, and Russia companies, the family amassing through international trade great wealth and political power. Henry Garway, Thomas’s first cousin once removed, was illustrative of the great influence wielded by the Garway family: Sir Henry was not only guild Master to the Drapers, the Mercers, and the Grocers, but he was also Lord Mayor of London during the turbulent years of Charles I.

With his family’s extensive connections to the sea trade, the young Thomas Garway sailed for the West Indies, Africa, and the East Indies. Shipwrecked on the coast of West Africa, he nonetheless made a fortune in gold and ivory. On his return to London, he became by virtue of his patrimony a member of the Worshipful Company of Drapers in 1656. The following year, he married Elizabeth, fathering eight children over the next eleven years. Thriving in business from 1658 through 1666, Garway took on four apprentices to assist him in trade.[5] Relying on his business connections and family relations, Thomas set up a chain of supply for coffee and tea with the Levant and East India companies, trading ventures in which the Garways invested, profited, and were heavily engaged.[6]

Just when Thomas Garway first opened his coffee house remains unknown, but he may have begun planning the business as early as 1656, purchasing tea in 1657, then opening and maintaining the Sultaness Head in Sweetings Rents from at least 1658, the year of his advertisement, until the year of the Great Fire of London in 1666.

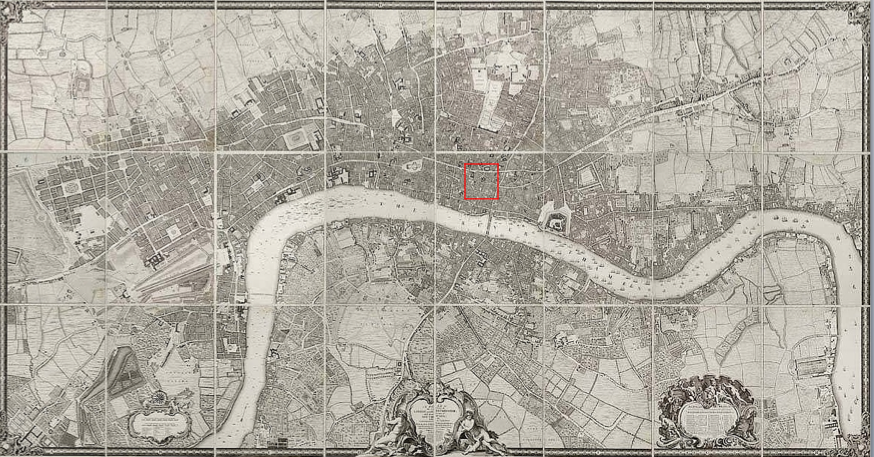

Broad Street and Cornhill

For his service of tea and coffee, Garway let a large house that was favorably located in the heart of London’s commercial and financial district. Sweetings Rents off Sweetings Alley in Broad Street ward[7] “contained only one house, a spacious building”[8] taxed at six hearths.[9] At least one of the hearths was devoted to the Sultaness Head for boiling water and brewing coffee and tea. The house was directly across the alley from the Royal Exchange and just a short walk to the Lord Mayor’s Mansion House. Up and down Throgmorton and Threadneedle streets, along Cornhill and Poultry and Cheapside, the Sultaness Head was nearly surrounded by the grand homes of the wealthy and the majestic halls and great houses of the City’s most prestigious guilds: Mercers, Grocers, Drapers, and the Merchant Taylors.

Garway not only catered to the freemen and liverymen of the companies but also to the officers and stockbrokers of the Royal Exchange and to the clerks, solicitors, and officials of the Lord Mayor’s offices. His patrons included men from nearby residences and trades – the rich merchants, affluent investors and speculators, and well to do shopkeepers. Nearby, the chairs and managers of the goldsmith banks ushered customers and coin from dawn to dusk. Drawn by the wealth and power of the ward, the intelligentsia – writers, journalists, doctors, and scientists – and not a few politicians congregated at the Sultaness Head to learn the gossip, rumors, and intelligence, domestic and foreign, flowing through the center of London.

The Royal Exchange

Within and without the Royal Exchange, it was reported that

“Here one may meet persons assembled from all parts of the universe, either to procure bills of exchange, to hire shipping, to learn news of the army, or the sailing of any particular vessel: in short, at London is known every thing that passes on the sea, and almost in all parts of the world to which they trade; for it must be allowed, that the English well understand the maritime art, and that they are true merchants on all seas with marvellous success and profit.”[10]

The wealth of the Royal Exchange and surrounding quarters was great and conspicuous. Owing to the cachet provided by the visit of Queen Elizabeth I in 1570, the Exchange prospered. The square building was four stories high with a double balcony and the “Pawn” or gallery of luxurious shops laden with expensive goods from all over the world. Ladies and gentlemen in gorgeous attire arrived in carriages to splurge and take a showy turn about the interior court.

A contemporary description recorded the lavishness of the scene:

“How full of riches…was that Royal Exchange! rich men in the midst of it, rich goods both above and beneath! There men walked upon the top of a wealthy mine; considering what eastern treasures, costly spices, and such like things were laid up in the bowels (I mean the cellars) of that place. As for the upper part of it, was it not the great storehouse whence the nobility and gentry of England were furnished with most of those costly things wherewith they did adorn either their closets or themselves? Here, if any where, might a man have seen the glory of the world in a moment. …. What artificial thing could entertain the senses, the fantasies of men, that was not there to be had? Such was the delight that many gallants took in that magazine of all curious varieties, that they could almost have dwelt there, (going from shop to shop like bee from flower to flower,) if they had but had a fountain of money that could not have been drawn dry. I doubt not but a Mahomedan (who never expects other than sensual delights) would gladly have availed himself of that place, and the treasures of it, for his heaven, and have thought there were none like it.”[11]

The Sultaness Head

A stone’s throw away from the Royal Exchange, aristocrats and the merchant elite gathered in Sweetings Rents at the Sultaness Head, a comfortable and well-appointed house that served out coffee and tea to refresh the body and quicken the mind. By 1660, the caffeine business was profitable enough to attract the attention of the government. Parliament granted the crown an excise tax of four pence on every gallon of coffee brewed and sold. Interestingly, the tax on tea was eight pence,[12] double that on coffee and indicating, perhaps, the greater charge on tea per cup. No doubt, Garway made a fine profit on the steeped leaf.

But for men of means, thirst and stimulants were the least of reasons to attend the Sultaness Head. However efficacious the caffeine, the real coin of the place was precious information. Thomas Garway provided a library of books, accounts, bulletins, and the weekly gazettes, and there was always lively discussion of the latest news by those in the know. Stock prices and quotes flew about the floor as traders concluded deals, capital ventures sought investors, and shipping lists hung prominently from the posting boards. Speculators sniffed out property developments, while everyone calculated intensely on the intelligence from the overseas trading companies and events on the Continent. The Sultaness Head was less about coffee and tea than commerce and finance. A businessman himself, Garway had a steady finger on the economic pulse of London.

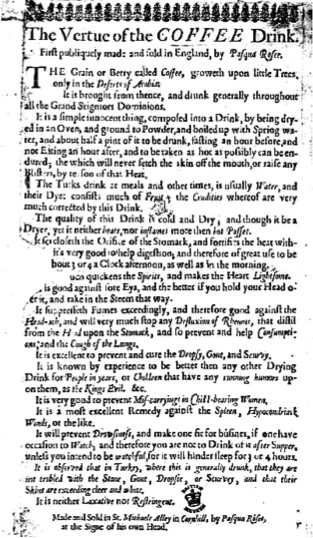

Pasqua Rosée and Bowman’s Coffee House

The Sultaness Head competed with other coffee houses in the neighborhood. Fifty yards south across Cornhill thoroughfare stood Bowman’s, the oldest coffee house in London. Bowman’s was initially the inspiration of Daniel Edwards, a prosperous merchant with the Levant Company who returned home from Turkey with his Greek servant Pasqua Rosée. Backed by Edwards, Rosée began serving coffee from an alley shed up against the churchyard walls of St. Michaels in 1652. Broadsheet handbills from the period bear the distinctively alien name of Pasqua Rosée who boasted that his coffee was the “First publiquely made and sold in England…at the Signe of his own Head.”[13]

Rosée capitalized on his foreign moniker and striking Greco-Turkish features to hawk his drink and to spawn a style of naming coffee houses with a Middle Eastern ring in which even the Sultaness Head indulged. Using the remarks of the writer and Parliamentarian Sir William Brereton in 1654, Ellis suggested that Edwards and Rosée “enjoyed a prodigious turnover” of at least £450 pounds sterling each year, a sum amounting to a small fortune,[14] all from a makeshift alley shed.

The ale taverns in the neighborhood complained and scapegoated the prospering foreigner for their loss of business. Rosée was forced to partner with the freeman and grocer Christopher Bowman who later moved the service in 1656 to a house across the way in St. Michael’s Alley to expanded space, patronage, and profits. Soon after, Rosée left, but Bowman continued to serve customers under his sign – a hand pouring coffee from a pot into a cup – in a “Coffee Room…up one pair of stairs”[15] until his death in 1662. The widow Bowman kept the place, and Bowman’s apprentices waited on patrons until 1665 when new management took over the shop, freshly styled the “Ould Coffee House,” which within a year burned in the Great Fire.[16]

Great Coffee House

But in truth, it was the successful Great Coffee House in Exchange Alley that came to pose far greater competition to Thomas Garway and the Sultaness Head. Known variously as the Great Turk or Morat’s Head, the Great Coffee House was owned by Walter Elford, a wealthy member of the Girdlers guild. Under the sign of Morat the Great, the Great Coffee House began in 1662 with an advertisement in The Kingdomes Weekly Intelligencer, offering coffee “on free cost” to celebrate the opening.[17] Unlike the Sweetings tenement, Elford’s was established especially as a coffee house[18] and contained four hearths for its several rooms. One or more of the hearths were dedicated to the roasting of coffee beans by means of a clockwork rotisserie powered by weights, a batterie de cuisine reputedly invented by Elford.[19]

The Great Coffee House was a part of grand, speculative plan to develop Exchange Alley and “maximize the commercial potential of the ancillary trading around the Royal Exchange.”[20] Opened by the developers as a pilot project around 1661, the coffee house was a lively and profitable place in which to invest. The scheme took advantage of the countless traders and brokers spilling over Cornhill from the stock exchange to wheel and deal with the moneyed goldsmith bankers of the nearby Grasshopper, Unicorn, and White Swanne.[21] Centrally located in Exchange Alley, the commercial potential of the Great Coffee House was gauged by the “extraordinarily high price” of the lease when Elford signed, paid a premium and first year’s rent of £300, and took rein.[22] Although entering the game later than Bowman’s or Garway’s, Elford’s was plusher, roomier, and with an upper class of customers: the Great Coffee House sold penny cups on volume and flourished. Within a few years, however, the promise of Elford’s and all other coffee houses was cut short by rats infected with bubonic plague.

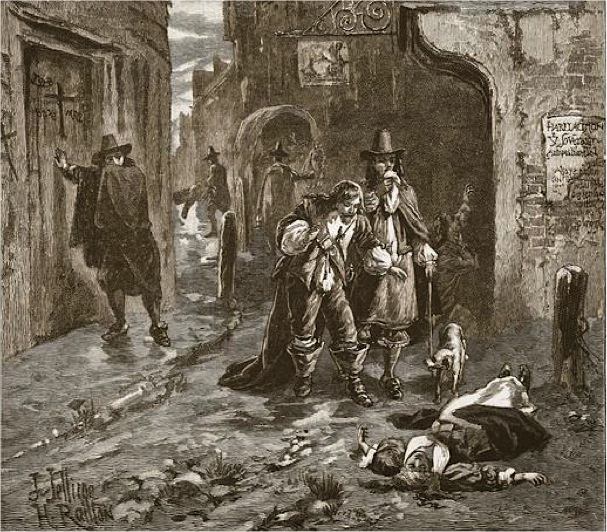

The Great Plague

In the summer of 1665, the Great Plague stalked the City of London and halted the prosperity of everything, including the wealthy districts surrounding the Royal Exchange. Measures were taken: great fires were set at the exchange entrances on Throgmorton and Cornhill streets, north and south of the building to ward off contagion and purify the air.[23] The rich and able fled the city. Samuel Pepys, the diarist and frequent customer of the Great Coffee House, described the scene:

“But, Lord! how sad a sight it is to see the streets empty of people, and very few upon the ‘Change. Jealous of every door that one sees shut up, lest it should be the plague; and about us two shops in three, if not more, generally shut up.”[24]

At such an awful time, Thomas Garway doubtless lacked for customers and closed shop. He, along with his family, most likely joined in the mass exodus from the City to wait out the epidemic. But the Plague was not the only calamity to visit the Sultaness Head. In the next year, the coffee house would shut for good after a stupendously fiery event.

The Great Fire

In 1666, the Great Fire of London destroyed Garway’s as well as Bowman’s and Elford’s. The fire started in the smoldering ovens of the royal baker in Pudding Lane just after midnight on a blustery Sunday morning, September 2nd. Within eighteen hours, what had been a small fire grew with gale force winds into a voracious firestorm engulfing the summer dry neighborhoods near London Bridge. Still rampant on Monday afternoon, the creature fire turned north, straight into the financial and commercial district.

As the denizens of Cornhill watched in disbelief, stones heated red hot exploded like cannon balls while tinder thatch and timber burst suddenly into flame. The luxurious Cheapside shops, the solid goldsmith banks, the Royal Exchange, and the grand guildhalls, were completely swallowed by the inferno. Mere steps away from the majestic colonnade of the stock exchange, Garway and Elizabeth, the children and apprentices, all escaped Sweetings Rents with their lives. The Sultaness Head was no more.

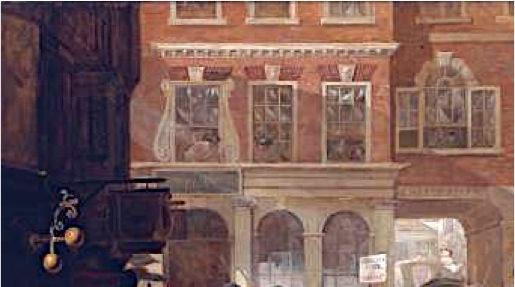

Exchange Alley

Over a year after the Great Fire, reconstruction began at the Royal Exchange. Charles II laid the base of a column at the north entrance of the new edifice to signal the rebuilding of the business community of Cornhill and adjacent wards. Exchange Alley was once again the site of intense speculative development. The charred debris removed and the land graded, the new Exchange Alley was a more orderly, considered plan with ample spaces and pathways, aided by building codes decreed in the aftermath of the conflagration. As before, coffee houses were a major element of the new expansion, and Walter Elford was approached to reconstitute the Great Coffee House in Exchange Alley. But he was unable to meet the terms of the developers, and Elford was excluded from the scheme.[25]

As the speculators cast about for likely tenants, Thomas Garway possessed the wherewithal to step up and sign what had been the Elford lease. Unlike the small tenements being rebuilt in Sweetings Rents, the Exchange Alley property was commodious and newly constructed of brick, a multi storied building of sixteen hearths,[26] the whole advantageously situated on a spacious corner; the premium and annual rent on such an establishment can only be imagined. The place was an auspicious beginning for Garway’s second venture in tea and called for another christening. Under the alias Garraway’s Coffee House, Thomas Garway and his new establishment were renowned as an energetic hub of economic activity – a literal warehouse of daily sales, auctions, and trading. In an ironic twist of fate, the once Great Coffee House became the even greater Garraway’s, a venerable London institution that rose from the ashes of the Sultaness Head to last over two hundred years.

Figures

1.

Wenceslaus Hollar (Czech, 1607-1677 A.D.)

Map of the City of London, 1673

Engraving: ink and color on paper

Dedicated to Sir Robert Vyner;

displaying the arms of the Twelve Great City Companies

The Crace Collection

British Library, London

2.

The Gazette: Comprising, The Sum of Foreign

Intelligence, with The Affairs now on foot in the

Three Nations of England, Scotland, and Ireland:

for Information of the People

(September 2-9 1658), no. 432, p. 801

3.

Drawing and Specimen

Sultaness Head Half-penny Token, ca. 1658-1666 A.D.

English: Interregnum and Restoration periods

Issued by the Sultaness Head Coffee House, London

Inscribed: “The Sultaness, A Coffee House” and

“Cornhill in Sweetings Rents”

Copper alloy, worn and corroded

Length: 19.8 mm, Width: 19 mm, Thickness: 1 mm

Weight: 1.775 g

4.

Drawing of the Coat of Arms of the House of Garway

“Argent, a Pile surmounted by a Fesse between four Leopards heads, Gules”

From John Gullim, Display of Heraldry Manifesting a More Easy

Access to the Knowledge Thereof, 1610, p. 256.

A shield with a silvery white ground divided by a triangular charge and

broad stripe into quadrants, each bearing the head of a leopard in red

5.

Claude-Joseph Vernet (French, 1714-1789)

Shipwreck , 1759

Painting: oil on canvas

Groeninge Museum, Bruge

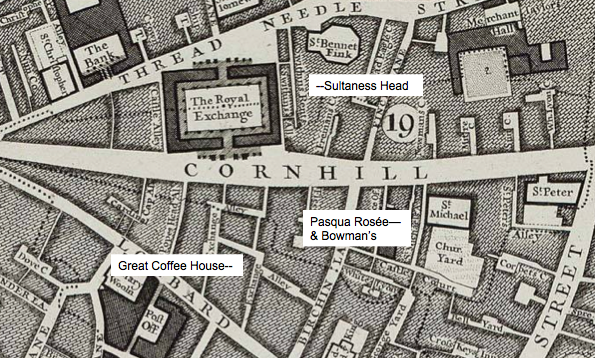

6.

Cornhill and Broad Street Wards, highlighted

John Rocque (English, ca. 1709–1762)

An Exact Survey of the Cities of London, Westminster and Borough

of Southwark with the Country near 10 miles round 1741-1745 and A Plan

of the Cities of London, Westminster & Southwark with contiguous

buildings, 1746

Engraved by John Pine, Bluemantle Pursuivant at Arms and Chief Engraver

of Seals to His Majesty

Engraving: ink on paper

Publisher: Harry Margary and Philimore & Co Ltd, Chichester.

7.

Sultaness Head Coffee House, location of

Detail of Cornhill from An Exact Survey of the Cities of London…, 1746

8.

Wenceslaus Hollar (Czech, 1607-1677 A.D.)

The Royal Exchange, London, 1644

Engraving: ink on paper

The Art Institute of Chicago

9.

Steven van der Meulen (Dutch, died ca. 1563-1564)

The Hampden Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, ca. 1565-1570.

Painting: oil on canvas transferred from wood panel

formerly the Hampden family and the Earls of Buckinghamshire at Hampden House

10.

Wenceslaus Hollar (Czech, 1607-1677 A.D.)

Interior Court of The Royal Exchange, ca. 1660

Engraving: ink on paper

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

University of Toronto

11.

Pasqua Rosée (active ca. 1652-1666 A.D.)

The Vertue of the Coffee Drink, ca. 1652-1656 A.D.

Printed handbill: ink on paper

British Museum

12.

Sultaness Head Coffee House, location relative to

Pasqua Rosée & Bowman’s Coffee House and Great Coffee House

Detail of Cornhill from An Exact Survey of the Cities of London…, 1746

13.

Detail of The Great Plague, 1665: Scenes in the Streets of London

from Cassell’s History of England (special edition)

London: A.W. Cowan, ca. 1890

14.

Artist unknown

Dutch School

The Great Fire of London, 17th century A.D.

Painting: oil on canvas

Museum of London

15.

Edward Matthew Ward (English, 1816-1879 A.D.)

The South Sea Bubble, a Scene in ‘Change Alley in 1720, 1847

Painting: oil on canvas

Tate Gallery

National Gallery of British Art, London

16.

Façade of Garraway’s Coffee House

Detail from Edward Matthew Ward (English, 1816-1879 A.D.)

The South Sea Bubble, a Scene in ‘Change Alley in 1720, 1847

Painting: oil on canvas

Tate Gallery

National Gallery of British Art, London

Notes

[1] The Gazette: Comprising, The Sum of Foreign Intelligence, with The Affairs now on foot in the Three Nations of England, Scotland, and Ireland: for Information of the People, no. 432, 2 September-9 September 1658, p. 801.

[2] Interestingly, Oliver Cromwell (English, 1599-1658 A.D.) died on Friday, September 3, 1658 around three o’clock in the afternoon, which meant that publication of the weekly The Gazette was delayed by at least two days pending the conclusion of the deathwatch of the Lord Protector. See Reginald Hanson, A Short Account of Tea and the Tea Trade (London: Whitehead, Morris & Lowe, 1876), p. 37.

[3] Booksellers and makers of quack medicines were early tradesmen using the weeklies for publicity. See E. Tucker, J.J. Thomas, and J. Harris, eds, “’The History and Mystery’ of Advertisements,” The Country Gentleman, July-January 1855, vol. 6, p. 178 and Thomas Herbert Russell, Advertising Methods and Mediums (Chicago: Washington Institute, 1910), pp. 28-30.

[4] John Gullim (English, ca. 1565-1621), Display of Heraldry Manifesting a More Easy Access to the Knowledge Thereof, 1610 (reprint, Kessinger Publishing, 2003), p. 256.

[5] “Garway Thomas,” Garway Family Tree, (May 24, 2006), accessed November 10, 2011, http://garraway.familytreeguide.com/getperson.php?personID=I0371&tree=BJTT2006&PHPSESSID=31f8fb3ed6c7ee94a1c4753d2a15c62b.

[6] Robert Brenner, Merchants and Revolution: Commercial Change, Political Conflict, and London’s Overseas Traders, 1550-1653 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 72, n. 58 and p. 223. In addition to the English overseas companies, it is likely that Thomas Garway traded with Dutch merchants who were connected to the Dutch East India Company, Amsterdam.

[7] John Sweetings, a wealthy land and property developer, owned numerous holdings in Broad Street and Cornhill wards, including Sweetings Rents and Sweetings Alley. See “Coffee-Houses of Old London,” The Et-cetera Magazine (London: August-December, 1872), vol. 1, p. 286; see also Tony Sweeting, “All About ‘Sweeting,’” Sweeting Genealogy Project, n.d., accessed November 10, 2011, http://www.sweeting.org/sweeting/sweeting.php.

[8] James Elmes, A Topographical Dictionary of London and its Environs (London: Whittaker, Treacher and Arnot, 1831), p. 383.

[9] Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Companion, Robert Latham and William Matthews, eds. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), vol. 10, p. 71; cf. “Hearth Tax: City of London 1662: Broad Street ward: St Bartholomew the Exchange Upper Precinct,” London Hearth Tax: City of London, 1662 (2011).

[10] “Vestiges Revived,” The European Magazine and London Review, no. 17 (December 1912), p. 432.

[11] Samuel Rolle (English, active ca. 1666 A.D.), “Meditations,” Shlohavot, or The Burning of London in the Year 1666: Commemorated and Improved in CX. Discourses, Meditations, and Contemplations (London: Robert Ibbitson for T. Parkhurst, 1667), part III, p. 47 in John William Burgon, The Life and Times of Sir Thomas Gresham (London: Rober Jennings, 1839), vol. 2, p. 505.

[12] Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany for British India and Its Dependencies (June-December, 1816) (London: Wm. H. Allen & Co., 1816), Vol. 2, pp. 45-46.

[13] Markman Ellis, “Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee-House, 1652-1666,” The London Journal (May 2004), vol. 29, no. 1, p. 6. See also William Harrison Ukers, All About Coffee (New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company, 1922), p. 55. For a transcription of the handbill see Henry Sampson, A History of Advertising from the Earliest Times (London: Chatto and Windus, 1874), p. 68-69.

[14] Samuel Hartlib (German-English, ca. 1600-1662), Ephemerides (August 4, 1654), no. 254, The Hartlib Papers, 2nd edn (Sheffield: HROnline, Humanities Research Institute, 2002), HP 29/4/29A-B cited in Markman Ellis, “Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee-House, 1652-1666,” The London Journal (May 2004), vol. 29, no. 1, p. 8. In today’s money, £450 is roughly worth £63,000 or $100,000.

[15] James Douglas, A Supplement to the Description of the Coffee-Tree (London: Thomas Woodward, 1727), p. 28 cited in Markman Ellis, “Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee-House, 1652-1666,” The London Journal (May 2004), vol. 29, no. 1, p. 12, n. 103.

[16] Markman Ellis, “Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee-House, 1652-1666,” The London Journal (May 2004), vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 1-24, esp. 9-11.

[17] The Kingdom’s Weekly Intelligencer, no. 51 (15-22 December 1662), p. 815 in Markman Ellis, “Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee-House, 1652-1666,” The London Journal (May 2004), vol. 29, no. 1, p. 14.

[18] Byron Fisher, The Supply and Demand Paradox: A Treatise on Economics (North Charleston: BookSurge Publishing, 2007), pp. 43-45.

[19] Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Companion, Robert Latham and William Matthews, eds. (University of California Press, 1983), vol. 10, p. 71.

[20] Markman Ellis, “Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee-House, 1652-1666,” The London Journal (May 2004), vol. 29, no. 1, p. 14.

[21] Journal of the Institute of Bankers (London: Institute of Bankers, 1886), vol. 7, pp. 331 and 334.

[22] For the Great Coffee House and its prime location, Walter Elford paid an astonishing premium of 200 pounds sterling and an annual rent of 100 pounds sterling (today totaling approx. $66,000) for a lease of twenty-one years. See Markman Ellis, “Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee-House, 1652-1666,” The London Journal (May 2004), vol. 29, no. 1, p. 14 and Markman Ellis, The Coffee House: A Cultural History (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004), p. 168.

[23] Walter Thornbury and Edward Walford, “The Royal Exchange,” Old and New London: Volume 1 (London: Cassell & Company, 1887), vol. 1, ch. 42, p. 500.

[24] Samuel Pepys The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Henry Benjamin Wheatley, ed. (Boston: Brainard Publishing Co., 1895), vol. 9, p. 44.

[25] Markman Ellis, “Pasqua Rosee’s Coffee-House, 1652-1666,” The London Journal (May 2004), vol. 29, no. 1, p. 14. Although Walter Elford refused the conditions of the new developers of Exchange Alley, he appeared to have moved his business eastward to a much smaller, corner property just off White-Lyon-Yard and George Yard, two alleys off of Birchin Lane, Cornhill. Still within a short walk from the Royal Exchange, Elford’s was no longer a “great” place, and the shop was simply called Elford’s Coffee House.

[26] Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Companion, Robert Latham and William Matthews, eds. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), vol. 10, p. 71.