No Harm in Tea

Tea received mixed reviews in seventeenth century Europe. Touted by herbalists and healers as a miraculous cure for nearly every ailment, tea contended with the strong and formidable opposition of medical conservatives throughout the Continent. According to the German doctor Simon Pauli and the French physician Guy Patin, its fiercest critics, tea was the bane of medicines, hastening death to all who partook. But tea had vocal advocates, staunch allies who rallied in print and practice, putting up a stiff defense of the brew to the benefit of general health, commerce, and sometimes personal gain.

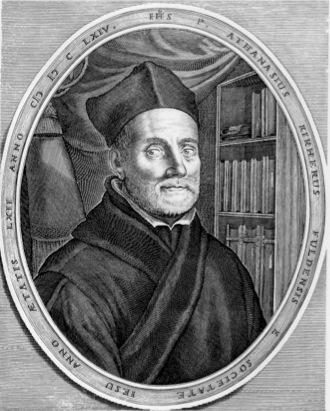

In Rome, the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher had heard of tea but did not at first believe in its medicinal efficacy. On drinking tea, Kircher was astonished and amended his opinion to become a champion of the leaf:

“It is a plant of great virtue, the likes of which, if I had not experienced it myself upon the invitation of some Fathers of our order, I would never have been led to credit, for joined to its diuretic faculty, it wonderfully relaxes every blockage of the kidneys and dissipates the heaviness of the head, so that literary men, or others who are compelled by the magnitude of their labors to stay up late at night, find no more noble or fitting remedy in all of nature, and although at first its taste is watery and somewhat bitter, in time it not only loses its unpleasantness, but soothes so well the itchings of the throat, that those who have taken up this drink find it hard to do without.”

Kircher went on to compose one of the most influential books on China. Published in 1667, China Illustrata was an encyclopedic work that included natural history and the mention of the tea plant:

“There is the plant called Cha, which not being able to contain itself within the bounds of China, hath insinuated itself into Europe: it aboundeth in divers regions of China, and there is great difference, but the best and most choice is in the Province Kingnan [sic], in the territory of the city Hocicheu [sic]. The leaf being boiled and infused in water, they drink it hot as often as they please: it is of a diuretic faculty, much fortifies the stomach, exhilarates the spirits, and wonderfully openeth all the nephritick passages or reins; it freeth the head by suppressing of fuliginous vapours, so that it is a most excellent drink for studious and sedentary persons, to quicken them in their operations; and though, at the first, it seemeth insipid and bitter, yet custom maketh it pleasant; and though the Turkish coffee administer the like cordiality, and the Mexican chocolate be another excellent drink, yet tea, if the best, very much excelleth them both, because, that chocolate in hot seasons inflameth more than ordinary, and coffee agitateth choler; but tea in all seasons hath one and the same effect.”[1]

Others on the Continent were less sanguine about the taste of tea. Physicians in the Netherlands attempted to introduce tea to the people of the ancient town of Dordrecht around the year 1670, but to no avail.

The southern Dutch palate resisted tea’s bitter charms to the extent that François Valentijn, the Dutch naturalist and native of Dordrecht, noted that the brew was held in contempt as heu wasser or “hay water.”[2]

Yet to some, tea was literally the fountain of life. In 1686, the German Janus Abraham von Gehema published a booklet with the descriptive title Ein Theetrank, ein bewahrtes Mittle zum gesunden langen Leben und Herrlicher Wassertrank für alle Menschen in allen Ständen nützlich…or “the tea beverage, a proven means toward living a long and healthy life, a wonderful draft of water that is useful for people of all walks of life.”[3]

After the ravages of the Thirty Years’ War, the Great Elector of Brandenburg, Freidrich Wilhelm I, set about reconstructing his German possessions by importing eminent physicians, philosophers, and scientists from Holland.

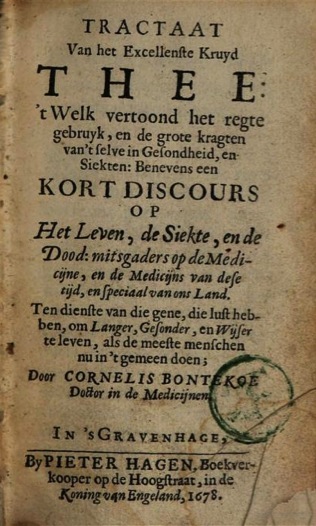

Among the Dutch attracted to the court at Berlin was the young doctor Cornelius Decker,[4] better known as Cornelis Bontekoe, the “Theedokter” and tireless advocate of tea. In 1678, Bontekoe wrote Tractaat van het excellenste kruyd Thee (Treatise on Tea, the Most Excellent Herb), the first of several publications such as Use and Abuse of Tea and Elementary Teachings in Medicine in which he promoted the extensive use of tea for a wide variety of ailments:

“We advise tea for the whole nation and for every nation. We advise men and women to drink tea daily; hour by hour if possible; beginning with 10 cups a day, and increasing the dose to the utmost quantity that the stomach can contain and the kidneys eliminate.”[5]

Bontekoe was a man who took his own medicine. According to him, there were few human maladies for which tea was not a remedy. He cured himself of stones by drinking tea [6] and his similar ministrations to the Great Elector were said to have cured his noble patron of gout.[7] Bontekoe further “observed that ‘two glasses of strong tea before an attack and a number of glasses after’ was an efficacious treatment of malaria, a pernicious disease in Holland.”[8]

Bontekoe’s personal consumption of tea was prodigious. Even if the cups were small and held but little, the amount of tea he drank was remarkable by any measure as he candidly admitted in his Treatise on Tea:

“I have no scruple in advising [people] to drink fifty or a hundred or two hundred cups at a time. I have often drunk as many in a fore- or afternoon, and many people with me, of whom not a single one has died yet. But I do not think that anyone need imitate this. I only allege it to show there is no harm in tea, so there is no reason to be afraid of drinking ten or twenty cups; it is not like wine or beer, which goes to the head as the saying is.”[9]

Later commentary on Bontekoe’s treatise criticized “the extravagance of its commendations of tea,”[10] but the Dutch East India Company, the prime European purveyor of the leaf, was exceptionally pleased with the doctor’s effusive praise of one of its most expensive and profitable imports. For his promotion of tea, Bontekoe was voted a gratuity as a gesture of appreciation by the Lords Seventeen, the Company board.[11]

Figures

1.

Artist unknown

Portrait of Athanasius Kircher, S.J. (German, 1602–1680), 1678

Engraving: ink on paper

from Giorgio de Sepibus (Italian, 17th century), Romani Collegii Musaeum Celeberrimum (The Celebrated Museum of the Roman College of the Society of Jesus) (Amsterdam, 1678)

2.

Jacobus Houbraken (Dutch, 1698-1780)

Portrait of François Valentijn (a.k.a. Franz Valentyn, Dutch, 1666-1725), 1724

Engraving: ink on paper

Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht

3.

Adrian Haelwegh (Dutch, 1639-ca. 1700)

Portrait of Cornelis Bontekoe (a.k.a. Cornelius Decker, Dutch, 1647-1685), ca. 1680

Copperplate engraving: ink on paper

4.

Title page

Cornelis Bontekoe (Dutch, 1647-1685)

Tractaat van het excellenste Kruyd Thee (Treatise on Tea, the Most Excellent Herb)

Hague: Pieter Hagen, 1678

Notes

[1] “Kingnan” and “Hocicheu” are mispellings of “Kiangnan” and “Hoeicheu,” i.e., Jiangnan 江南 and Huizhou 徽州. Athanasius Kircher, S.J. (German, 1602–1680), China monumentis, qua sacris qua profani, nec non varus naturae & artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata (China elucidated through its sacred, profane [literary] monuments, natural elements, arts and other arguments) (Amsterdam: Elizée,1670), ch. 6, pp. 242-244. Cf. Johannes Nieuhof (1618-1672), An embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, emperor of China: delivered by their excellencies Peter de Goyer and Jacob de Keyzer, at his imperial city of Peking wherein the cities, towns, villages, ports, rivers, &c. in their passages from Canton to Peking are ingeniously described by John Nieuhoff; also an epistle of Father John Adams, their antagonist, concerning the whole negotiation; with an appendix of several remarks taken out of Father Athanasius Kircher; Englished and set forth with their several sculptures by John Ogilby (London, England: Printed for the Author, 1673) [Kircher appendix] “Of Strange or Foreign plants in China, ch. 5, pp. 408-411, esp. 408.

[2] François Valentijn (a.k.a. Franz Valentyn, Dutch, 1666-1725), Oud en nieuw Oost-Indiën (History of the Old and New East Indies) (Dordrecht & Amsterdam, 1724-1726), iv, ii, p. 18 cited in “A View of the Tea Trade of Europe,” Monthly Magazine and British Register, vol. 6, p. 30. pp. 30-33.

[3] Janus Abraham von Gehema (German, 1645-1700), Ein Theetrank, ein bewahrtes Mittle zum gesunden langen Leben und Herrlicher Wassertrank für alle Menschen in allen Ständen nützlich (The tea beverage, a proven means toward living a long and healthy life, a wonderful draft of water that is useful for people of all walks of life) (Bremen, 1686) cited in Ernst Von Bibra (German, 1806-1878), “Tea (Thea chinensis),” Die narkotischen Genubmittel und der Mensch (Nuremburg: Wilhelm Schmid, 1855) reprinted as Plant Intoxicants: A Classic Text on the Use of Mind-Altering Plants (Rochester: Healing Arts Press, 1995), ch. 3, pp. 37-38.

[4] For Bontekoe see Christoph Schweikardt, “More than just a Propagandist for Tea: Religious Argument and Advice on a Healthy Life in the Work of the Dutch Physician Cornelis Bontekoe (1647-1685),” Medical History, vol. 47, no. 3, (July, 2003), pp. 357–368 and Evert Dirk Baumann, De docter en de geneeskunde (The Doctor and Medicine),” part 2, De wetenschap (Science) (Amsterdam: H. Meulenhoff, 1915), p. 84.

[5] Cornelius Decker (a.k.a. Cornelis Bontekoe, Dutch, 1647-1685), Medizinischen Elementarlehre (Elementary Teachings in Medicine, ca. 1680 A.D.) cited in M. van Wijhe, “The History of Caffeine as Used in Anaesthesia,” The History of Anesthesia, José Carlos Diz, et al., eds. (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2002), p. 101.

[6] Cornelius Decker (a.k.a. Cornelis Bontekoe, Dutch, 1647-1685), Tractaat van het excellenste kruyd Thee (Treatise on Tea, the Most Excellent Herb, 1678) cited in Harold J. Cook, Matters of Exchange: Commerce, Medicine, and Science in the Dutch Golden Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 294 and 452-453, n. 105 and Alan Macfarlane, The Savage Wars of Peace: England, Japan and the Malthusian Trap (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1997), p. 139.

[7] Cornelius Decker (a.k.a. Cornelis Bontekoe, Dutch, 1647-1685), “Drei neue curieuse Tractätgen von dem Brand Café, chinesischen The und der Chocolata,” Kurze Abbandlung von dem menschlichen Leben, Gesundheit, Krankheit und Tod (Rudolstadt, 1692) cited in Michael North, Material Delight and the Joy of Living: Cultural Consumption in the Age of Enlightenment in Germany (Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008), ch. 9, pp. 155 and 221, n. 10.

[8] Alan Macfarlane, The Savage Wars of Peace: England, Japan and the Malthusian Trap (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1997), p. 203.

[9] Cornelius Decker (a.k.a. Cornelis Bontekoe, Dutch, 1647-1685), Tractaat van het excellenste kruyd Thee (Treatise on the Most Excellent Tea Herb, 1678) (Hague: Pieter Hagen, 1678).

[10] “A Review of Tea; its Effects, Medicinal and Moral. by G. G. Sigmond, M.D.,” The Literary Gazette, no. 1177 (August 1839) (London: H. Colburn, 1839), p. 500.

[11] Charles Taylor, The Literary Panorama, s.n., (May,1807), vol. 2, p. 351.