The Song of Tea

Lu Tong (790–835)

Writing in Haste to Thank Imperial Grand Master of Admonishment Meng for Sending New Tea

The sun is as high as a ten-foot measure and five, and I am deep asleep.

The general bangs at the gate loud enough to scare the Duke of Zhou!

He announces that the Grand Master sends a letter, the white silk cover is triple-stamped.

Breaking the vermilion seals, I imagine the Grand Master himself inspecting these three hundred moon-

shaped tea cakes.

He heard in the New Year that they entered the mountain, startling the hibernating insects that rise

on the spring winds.

The Emperor must be the first to taste Yangxian tea. Until then, the one hundred plants dare not

bloom.

Benevolent breezes intimately embrace pearly tea buds, the early Spring coaxing out sprouts of golden

yellow.

Picked fresh, fired till fragrant, then packed and sealed; tea’s essence and goodness is not wasted.

Such venerable tea is meant for princes and nobles. How could it reach the hut of this mountain

hermit?

Shutting the brushwood gate against vulgar visitors, donning my gauze cap, I simmer and taste tea in

solitude.

Jade green clouds draw a steady wind, gleaming white froth gathers on the side of the bowl.

The first bowl moistens my lips and throat.

The second bowl banishes my loneliness and melancholy.

The third bowl penetrates my impoverished core, wherein are only the five thousand canonic scrolls.

The fourth bowl raises a light perspiration, all life’s inequities dispel through my pores.

The fifth bowl purifies my flesh and bones.

The sixth bowl leads me to the Immortals.

The seventh bowl I cannot drink, feeling only a pure wind rising beneath my wings.

Where is Mount Penglai, the Isle of Immortals?

I, Master Jade Stream, ride the pure wind, wishing to return.

Gathered on the mountaintops, the Immortals oversee the earthly realm,

High and lofty, removed from wind and rain.

Do they know the bitter lives of the myriad peasants toiling below the cliffs?

Thus, I ask the Grand Master about these common folk.

Whether or not, in the end, they will ever rest.

盧仝

走筆謝孟諫議寄新茶

日高丈五睡正濃,軍將打門驚周公。口云諫議送書信,

白絹斜封三道印。開緘宛見諫議面,手閱月團三百片。

聞道新年入山裏,蟄蟲驚動春風起。天子須嘗陽羨茶,

百草不敢先開花。仁風暗結珠琲瓃,先春抽出黃金芽。

摘鮮焙芳旋封裹,至精至好且不奢。至尊之餘合王公,

何事便到山人家。柴門反關無俗客,紗帽籠頭自煎吃。

碧雲引風吹不斷,白花浮光凝碗面。

一碗喉吻潤,兩碗破孤悶。三碗搜枯腸,唯有文字五千卷。四碗發輕汗,

平生不平事,盡向毛孔散。五碗肌骨清,六碗通仙靈。

七碗吃不得也,唯覺兩腋習習清風生。蓬萊山,在何處。

玉川子,乘此清風欲歸去。山上群仙司下土,

地位清高隔風雨。安得知百萬億蒼生命,

墮在巔崖受辛苦。便為諫議問蒼生,到頭還得蘇息否。

Source

Yuding quan Tangshi 御定全唐詩 (Imperially Commissioned Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty), juan 388, pp. 4a–5a.

Figure

Artist unknown

Portrait of Tao Hongjing as a Daoist, detail

Yuan dynasty, 14th century

Album leaf: ink and color on paper

National Palace Museum, Taipei

The Autobiography of Imperial Instructor Lu

Lu Wenxue zizhuan 陸文學自傳, The Autobiography of Imperial Instructor Lu

by

Lu Yu (circa 733–804)

An Annotated Translation, Introduction, and Commentary by Steven D. Owyoung

Introduction to The Autobiography of Imperial Instructor Lu,

an excerpt from the forthcoming book on the life and art of the Tang tea master, Lu Yu (circa 733-804), author of the Chajing, the Book of Tea

Lu Yu 陸羽 (circa 733–804) was a scholar who lived during the eighth century in Tang dynasty China. He was renowned as the author of the Chajing 茶經, a treatise also known as the Book of Tea. The Chajing was a pioneering study of tea that described the cultivation of the plant, the manufacture of caked tea, and the preparation and service of the leaf as a beverage. Comprised of ten parts in three volumes, the Book formalized and codified the implements, utensils, and methods employed in the art of tea. By writing the Chajing, Lu Yu also compiled the first anthology of tea as well as the first hagiography of historical and mythical figures associated with the leaf. For centuries, the Book of Tea remained the exemplar of writings on tea, and Lu Yu, the foremost practitioner of the art of tea.

In addition to the Chajing, Lu Yu wrote an autobiography, a personal history in which he recounted his early life as a foundling and fledgling scholar. Known as the Lu Wenxue zizhuan 陸文學自傳 or The Autobiography of Imperial Instructor Lu, the account was written when Lu Yu was just twenty-eight years of age. It is a wonder how such a young man of so little experience or social standing might warrant a biographical report, much less possess the conceit to write it himself. Over the centuries, numerous profiles and chronologies have offered various accounts of his early activities and attainments, but it is Lu Yu’s very own account that served as the touchstone for understanding the formative years of his life.

Written in the third person, The Autobiography of Imperial Instructor Lu presented a detailed and often intimate portrait of Lu Yu, from childhood through young adulthood. The first lines of his account provided the raisons d’être for writing a personal record so early in life. Firstly, Lu Yu explained that his surname and given name — Lu 陸 and Yu 羽 — were in question, and so too was his courtesy name, Hongjian 鴻漸, and that some people often confused his names out of ignorance. Secondly, not only were his names and origins at issue but his personal integrity as well.

Moreover, Lu Yu was acutely aware that some who did not know him were daunted by his ugliness, his coarse appearance and disheveled dress, and further unsettled by his speech impediment and cantankerous disposition, not to mention his often distracted and distant air. All of these physical and personal traits conspired to present him at a disadvantage, if not as downright disagreeable, his character questionable. To doubters of his goodness, he hastened to rectify their mistaken impression. To his friends and acquaintances, Lu Yu reassured all that he was ever forthright, humble, and true.

Having explained his name and nature, Lu Yu next claimed an early inclination towards reclusion, to shutting his door to the outside world to live in seclusion. He described how he read books at his leisure in a lone hut along the banks of a broad stream and welcomed only the society of learned monks and scholars. He wrote that he habitually disappeared into the countryside, simply dressed in peasant clothes, to ply the abundant waters of the riverine south and roam about without direction. He confessed to attacks of depression and despair such that he returned from his wanderings each night exhausted and distraught. He knew that people who saw him whispered and thought him quite mad.

Midway through the autobiography, Lu Yu revealed that he was once a foundling forsaken near a Buddhist monastery in Jingling on the Hubei plain west of Wuhan. Discovered by the friary abbot, he was rescued and raised as a novice, trained from childhood to lead a cloistered existence devoted to scripture and monastic routine. But though just an adolescent boy, Lu Yu questioned the monkish and celibate life, an existence without the joys of family, writing, or books. Dissatisfied with studying only religious teachings, Lu Yu requested to be taught secular writings, specifically the Confucian canon, only to be refused by the abbot, who insisted that the boy learn solely from Buddhist scripture. Lu Yu, however, persisted, engaging whomever beyond the priory walls in conversation, hoping to learn more. To blunt Lu Yu’s heretical desire for worldly knowledge, the abbot feigned disaffection and punished him, forcing the boy with harsh, demeaning labor and physically abusing him for his stubborn disobedience. Denied and maltreated, Lu Yu ran away from the monastery and joined a troupe of itinerant performers for whom he happily indulged his gift for farce and satire, performing stock comedic roles and writing satirical skits and jokes. Desperate to find his fugitive ward, the abbot personally searched for Lu Yu, only to discover him acting on stage, reveling in the limelight before approving audiences as an uncommon player of the demimonde at the very lowest rungs of society. To cox the boy to return to the priory, the abbot relented, granting Lu Yu dispensation and promising to allow him limited study of secular writings.

Yet, even while back at the monastery, Lu Yu and his thespian talent were still in demand. Officials, who had seen him perform on stage, sought him out as a young but dazzling master of ceremonies for their requisite entertainment of visiting guests and officers. In the face of command performances, the abbot yielded, allowing the boy to appear at events sponsored by the local and prefectural governments. On one pivotal occasion, Lu Yu met a high official from the imperial capital, an influential governor who set him firmly on a lifelong path of learning and scholarship by sending him to school and later appointing him to the prefectural staff. Subsequent Jingling officials also became benefactors, mentors, and friends, sharing with him their interests in tea and poetry, and setting by example the intellectual rigor and proper conduct of the scholarly, accomplished gentleman.

At age twenty-one or so, Lu Yu traveled west to Sichuan to conduct research on the botanical nature and horticulture of tea. Returning to Jingling, he was then forced by rebel armies in the north to seek the relative safety of the south by following the exodus of refugees across the broad waters of the Yangzi. He traveled to Zhejiang and eventually settled in Huzhou, a tea-growing region along the southwestern shores of Lake Tai.

Arriving in Huzhou as an émigré with few friends, Lu was unknown and suspect to those he met. And, although he was well educated and connected elsewhere, Lu Yu was initially misunderstood by Huzhou society such that he felt compelled to shield himself and his reputation in a subjective but factual account. Thus, amid rumor and misconception, Lu Yu chose autobiography as the means by which he conducted his self-defense.

Lu Yu set his thoughts to paper using brush and ink and initially wrote notes in cursive script as words and phrases came to mind, for as a learned scholar his biography would be a literary endeavor full of allusion. As the themes and structure took shape, his composition went through several drafts before the final manuscript was inscribed in a clear hand, dated 761, and mounted as a small handscroll. Lu Yu then passed the scroll to friends so that they might read and copy it for themselves. Lent and borrowed, read and copied, the autobiography gradually circulated more widely, passed from hand to hand among the literati of Huzhou and spread by his admirers to the distant provinces.

Lu Yu concluded his autobiographical account with several titles of his writings. Two compositions, written in response to uprisings against the central government, emphasized his loyalty to the Tang throne and state; the verses further supported by a treatise on the duties between sovereign and vassal. Remaining titles disclosed his keen interest and knowledge in lexicography, biography, genealogy, and history as well as his expertise in the occult. Significantly, one work in three volumes emphatically declared that he had already written the Book of Tea.

It was clear from the structure of the Autobiography that Lu Yu considered the first and last portions of the text as the most important: his good name and his scholarship were the defining contours of his life. As Lu Yu became known and eventually famous, renowned scholars and high officials supported his person and activities until the end of his days.

__________________

Cover Illustration

Chajing 茶經, calligraphy by Fu Shen 傅申 (Shen C.Y. Fu, 1937–2024), noted Chinese art historian, calligrapher, painter, and connoisseur. Former Research Scholar of calligraphy and painting, National Palace Museum, Taipei; Associate Professor, Yale University; Senior Curator of Chinese Art, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; and Professor, Graduate Institute of Art History, National Taiwan University.

Chajing, The Book of Tea

Chajing, The Book of Tea

by

Lu Yu (circa 733-804)

An Annotated Translation, Introduction, and Commentary by Steven D. Owyoung

Introduction to the Chajing,

an excerpt from the forthcoming book on the art of tea

The art of tea was one of the great cultural achievements of imperial China. For over two thousand years, from the Han through the Qing dynasties, tea was a priceless tribute offered to the throne and nobility. Ubiquitous, tea was also enjoyed by aristocrats and commoners alike in the markets and towns throughout the empire. Brewed by acclaimed masters in the mansions of the rich, tea became an essential form of etiquette and politesse. Among the intelligentsia, tea was a high art that nurtured literary pursuits and philosophical discourse.

Like all pleasures of the palate, drinking tea focused on the sensual realms of fragrance, color, and flavor. Connoisseurs and tea masters noted and appreciated the myriad qualities and forms of the leaf, conveying their knowledge as arbiters of taste. There were further aspects of tea, especially those that encompassed the preparation and service of the beverage. In time, the making of tea evolved into performance, highlighting technical skills and personal styles, and thereby offering practitioners recreation, entertainment, and artistic expression. Moreover, the art of tea influenced material culture, notably the decorative arts, in the preference of wares for brewing and drinking as well as serving utensils and preparatory equipage. As a communal endeavor, tea was bound by a concern for the proper and congruent relationship between host and guest. Tea fostered artistic activity, intellectual and scholarly exchange, inspiring rhapsodies, poetry, and prose devoted to the leaf. At the highest levels, the art of tea was a portal to philosophical insight and spiritual attainment.

Historically, the rise and spread of tea began in the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–C.E. 220) from at least the second century B.C.E., when the enfeoffed aristocracy enjoyed tea as an herb and beverage and presented the finest leaf to the imperial palace and the emperor. The appreciation of the art of tea as a profound experience of beauty and meaning flourished in the third century and found early expression in the poetry of the Western Jin dynasty (265–316). By the Tang (618–907), the service of tea was a complete artistic experience, a refined attainment enhanced by beautiful works and tasteful surroundings. As an aesthetic pursuit in the eighth century, the art of brewing the leaf corresponded with the growth of the tea industry as an economic and political force.

In tradition, the scholar Lu Yu 陸羽 (circa 733–804) was credited with the rise of tea during the mid-Tang. He vigorously promoted tea culture through his writings and activities for much of his life. In 780, Lu Yu completed and published the Chajing 茶經, the first treatise ever on the plant, leaf, and drink. Known as the Book of Tea, the work set forth the technical and aesthetic elements of tea and transformed them into a formalized and codified system. During his lifetime, Lu Yu became the embodiment of the perfected tea master, and the Chajing profoundly influenced contemporary Tang and later forms of tea.

Until Lu Yu and the Chajing, little was commonly known about tea or the art of tea. The people of tea growing regions beyond the Yangzi had long harvested, processed, and drunk tea, but knowledge of its use as food, remedial, tonic, and drink was bound to the south where for millennia the plant grew and flourished as part of local culture and custom. From the Western Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–C.E. 8) onward, tea was presented as tribute and sent north to the imperial capital and the palace stores, the inventory used in food and drink, the cuisine of the emperor, nobility, and high officials. For centuries afterward, empirical knowledge of tea was a privileged realm, the purview of accomplished masters — aesthetes, monks, chefs, physicians, apothecaries, and alchemists — its mysteries and utility passed from teacher to disciple. Information about the herb and plant was scattered and buried in ancient tomes, and only the few understood its botanical nature or its proper brewing. Fewer still enjoyed tea as a form of connoisseurship and art, and it was the rare figure who pursued tea as an aesthetic quest. With the Chajing, Lu Yu dispelled the air of exclusivity surrounding tea and changed the art from an elite activity into a social custom of universal appeal.

Lu Yu was an authority on every aspect of the tea plant and herb. When he finished the Chajing, the book was the first and most comprehensive, methodical treatment of tea ever written. Introducing tea as a botanical, Lu Yu identified the origins of the tree and the character of its horticulture. He noted the medicinal uses of tea and its herbal potency and described the harvest and manufacture of tea as well as its preparation and service. Lu Yu described and defined the implements and utensils employed in making tea, and he explained the brewing and drinking of the beverage. Moreover, he set forth rules for tea and compiled an anthology of the herb taken from literature and history. In all, the Chajing was an imposing work of scholarship that expanded the intellectual and literary boundaries of the Tang, while faithfully mirroring the chic activities of a gilded age.

Lu Yu considered tea an evocative art, a subtle matter of the hearth and heart. As a tea master, he strove to produce the fullest expression of the leaf – its hue, scent, and flavor:

“The color of tea is xiang 緗, light yellow. Its penetrating fragrance is exceedingly beautiful…Tea that tastes sweet is jia 檟. That which is not sweet but bitter is chuan 荈. Tea that tastes bitter when sipped but sweet when swallowed is cha 茶.”

To create his tea, Lu Yu used a fine powder ground from caked tea. As described in the Chajing, caked tea was a highly processed and expensive form of the leaf. Harvested leaves were first cooked over steam. Pressed to remove excess water, the leaves were then pounded to a pasty pulp, set in molds, and dried over a low charcoal fire. Depending on the design of the mold, the finished tea resembled a delicate wafer or thin cake shaped as a small but perfect round, square, or flower. In the art of tea, it was the task of the tea master to turn the caked tea into a refined beverage of liquor and foam.

As a poet, Lu Yu exalted the sensuousness of the brew:

“Froth is hua 華, the floreate essence of the brew…Hua 花 froth resembles date blossoms floating lightly upon a circular jade pool or green blooming duckweed whirling along the winding bank of a deep pond or layered clouds floating in a fine clear sky. Mo 沫 froth resembles moss floating in tidal sands or chrysanthemum flowers fallen into an ancient ritual bronze…Reaching a boil, the thickened floreate essence of the brew then gathers as froth, white on white like piling snow.”

Lu Yu began preparing tea by arranging the equipage on a table or stand for display; afterwards, he placed each utensil and implement within reach around him. Next, he lit the brazier, placing a live coal in the ash to light a layer of fine charcoal. Then, he filtered spring water into the cauldron to heat. At the open vent of the brazier, he toasted a cake of tea before grinding it with a mill. The ground tea was sifted to a fine powder, and as the cauldron began to boil a measure of salt was added to the water. The tea powder was then poured into the boiling water to froth and foam. A dipper of hot water was next added to lower the liquid to a simmer. Finally, the frothy tea was ladled into bowls and served.

As presented by the master, even a formal tea appeared to be a casual affair. As Lu Yu prepared the brew, he may have engaged his guest with a comment on the source of the charcoal or a mention of the spring from which the water was drawn that morning or a description of the garden where the tea was grown or a remark on the color of the tea bowl. Or he might have said nothing at all, allowing the beauty of the moment to express everything.

Hidden within Lu Yu’s leisurely asides and silent demonstrations was a profound understanding of tea — a formidable physical and mental regime of technique and concentration that directed his spare, unhurried movements as he brewed the herb. Such knowledge and discipline formed the content of the Chajing and provided the fundamental methods and principles for the art of tea.

The most challenging and sophisticated facets of the art of tea were reflected in the Chajing. At its simplest and most basic preparation, tea was the making of a beverage; in its highest and purist form, tea was an ascetic practice concerned with health, longevity, and the search for immortality. The Book of Tea confirmed the ancient history of tea and upheld its poetic and spiritual aspirations. As an aesthetic pursuit, tea possessed a philosophic quality, one especially attuned to the metaphysical concerns of the nature of Being. In the hands of Lu Yu and the masters before him, the art of tea was believed to be an expression of cosmic Harmony and transcendent Truth.

For his teachings in the Book of Tea, Lu Yu adopted the formulaic mode of sectarian texts. He was inspired by scripture and assumed the didactic and admonitory tone of religious writings. He took Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist works as his models and chose the term jing 經, meaning book or scripture, for his title to signify the canonic character of the Chajing 茶經.

The form and content of Daoist writings greatly influenced Lu Yu. He wrote the Book of Tea in three scrolls and ten parts in keeping with the structure of Daoist holy books and monastic manuals, changing the religious themes to the concerns of tea. Daoist scripture was considered celestial and eternal, written by the spirits and enshrined in Heaven. By emulating works of such divine origin and permanence, Lu Yu sought to present the Chajing and the art of tea as inspired, revelatory, and enduring. In further accord with Daoist belief, Lu Yu identified the mystical and alchemical tradition of tea as symbolic of the herb of immortality, the elixir of life.

The Chajing revealed much about Lu Yu and his approach to the art of tea. When describing the selection and use of accouterments, he was meticulous, specifying the precise number and kind of equipage and citing the exact measurements and capacity of each implement. He applied an unusual yet precise knowledge of techniques and materials to the design and making of tea utensils, describing the minutiae of a mold assembly of a bronze brazier in one instance and stipulating in another the use of a certain rattan for making fine paper. A consummate art connoisseur, Lu Yu revealed the aesthetic subtleties of tea and its related arts, weighing the merits of various media and wares according to their physical properties and aesthetic attributes. The art of tea required utensils possessed of meaning, refinement, and beauty. Lu Yu was keenly aware of the appearance of materials, particularly woods, and recommended baskets of fine bamboo polished to a rich luster. For tea bowls, he favored celadon ceramic wares, because their green glazes enhanced the color of tea. Some implements were chosen for their deep ceremonial significance, their distinctive shapes and materials evoking the sacred ritual of the ancient past.

A stickler for form, Lu Yu was dogmatic and insisted that the complete set of twenty-four articles for tea was absolutely indispensable, especially when making tea for the high nobility. Yet, if brewing tea in the wilderness, he conceded that all but the most essential utensils were expendable. Pragmatic and inclusive, Lu Yu allowed for a great range of styles in tea from the ornate and aristocratic to the plain and rustic, and everything else in between.

Lu Yu revealed his insights and explored the aesthetic dimensions of tea in a language that was highly literary and often poetic. Generally, he wrote in a crisp orthodox style characterized by short phrases of pithy prose. Even when composing prosaic descriptions of equipage and implements — his most formal and methodical moments — Lu Yu paraded his knowledge and entertained twists of rhetoric that were engaging and refreshing. Using esoterica gleaned from his linguistic studies and extensive travels, he challenged scholars with odd dialects and diction as well as a liberal sprinkling of exotic synonyms for the names of ordinary utensils.

In style and manner, Lu Yu was by turns loquacious and laconic. He drew on elegiac imagery for his vivid portraits of tea and often lapsed into verse, once swelling lyrically over the semblance of tea to autumnal flowers cast into an archaic bronze. The mundane and miniscule, he often made quite grand and exciting. With theatrical flair, he spun a simple but dramatic and beautiful account of boiling water, a series of slow mesmerizing stages of bubbling fish eyes and strung pearls that culminated in a sea-surge eruption of flying billows and overflowing froth. He criticized connoisseurs and dismissed their preoccupation with the leaf and its myriad forms. On the finer epicurean points of tea, Lu Yu turned silent and covert, cloaking critical aspects in arcane tradition and mystery. More than just a guide to tea, the Chajing provided the first intimate look at the personal style and innermost thoughts of a highly accomplished and imaginative tea master of the middle Tang.

The Chajing made Lu Yu a celebrity. Scholars admired his knowledge and independent thinking and valued his brilliant and often dramatic spirit. Tea merchants were among his most ardent admirers as they watched stock and sales rise with the popularity of tea spurred by his book. Even the throne awarded him rank and offices: Great Supplicator of the Court of Imperial Sacrifices and Imperial Instructor to the Heir Apparent. But he spurned fame and popularity, and despite the grand titles bestowed on him, he skirted the bonds and perils of palace service, coveting his freedom and declining the official posts. His disdain for wealth and power was illustrated in one of his most famous songs, a lament in which he pined for the simple life of his hometown and his lost youth:

“I do not desire cups of white jade

Nor desire wine vessels of yellow gold.

I do not desire mornings at court

Nor desire evening audiences.

I do have a thousand, ten thousand desires

For the waters of the West River

Flowing just beyond the walls of Jingling.”

Following lifelong habits, Lu Yu remained a wanderer — traveling, staying at hermitages and temples, and visiting tea gardens. He was praised in the poems of his many friends who documented his tea drinking and his tours of tea gardens throughout the south. Lu Yu continued composing scholarly works until his death around 804, but none of his volumes on the connoisseurship of water or history or genealogy ever achieved the fame of his most celebrated work, the Book of Tea. In Lu Yu’s memory, tea merchants commissioned small ceramic figures of him and gave them to favored customers. His encounters in tea became legendary, enhancing his renown as the ultimate tea master and elevating the Chajing to a venerated canon.

Lu Yu and the Book of Tea had a profound impact on the history and culture of China. He brought about the establishment of Tang imperial tea estates that elevated tea as an offering within the palace tribute system and the ancestral rites of the emperor. His preference for green tea bowls prompted the imperial kilns of successive dynasties to produce and perfect verdant wares of celadon. Driven by social fashion and entrepreneurial production, tea burgeoned in the field and marketplace, an economic expansion that led to the taxation of tea and the banking institution of credit transfers known as “flying money.” The wealth and power generated by tea during the latter eighth century caused the corruption and downfall of high ministers as well as periods of political disruption and social unrest. As a distinctive mark of cosmopolitan and continental culture, tea became an international commodity. Presented as gifts at the distant courts of Korea and Japan, tea was treasured as a great rarity, and there clerics and aristocrats practiced the art of tea assiduously, inspiring the transformation of the social and cultural fabrics of both peninsula and archipelago.

The Book of Tea generated studies of the leaf and the art of tea by later masters and connoisseurs. And although the methods and manners of tea changed in time, Lu Yu’s opus magnum was the literary model, the criterion, for all subsequent works on tea, and Lu Yu himself was the epitome of the tea master. From the Tang through the Qing dynasty, down to the present day, despite over a thousand years of change, the Chajing remains, without exception, the most enduring and influential writing on the art of tea.

__________________

Cover Illustration

Chajing 茶經, calligraphy by Fu Shen 傅申 (Shen C.Y. Fu, 1937–2024), noted Chinese art historian, calligrapher, painter, and connoisseur. Former Research Scholar of calligraphy and painting, National Palace Museum, Taipei; Associate Professor, Yale University; Senior Curator of Chinese Art, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; and Professor, Graduate Institute of Art History, National Taiwan University.

Water as Metaphor

Once, the philosopher Confucius (a.k.a. Master Kong, circa 551–479 B.C.E.), stood staring intently at water flowing eastward. A disciple saw him and posed a question, addressing the sage as Gentleman:

“Why, when the Gentleman sees a great body of water, you are certain to gaze upon it?” Master Kong said, “When water is great, it sustains all life everywhere without motive; this resembles virtue. It flows down through the lowland, overlapping and bending, following by necessity its course; this resembles propriety. Ah, its sparkling waters, untroubled and undwindling; this resembles the Way. Overflowing its banks, it goes swift as an echo down a hundred gorges without fear; this is courage. As a standard of measurement, it is perpetually level; this resembles a model principle. Filled to overflowing, there is no need for a leveling stick; this resembles rightness. Soft and compliant, it penetrates the smallest places; this resembles judgment. Going into and out of it, one becomes fresh and pure; this resembles goodness. Altered by ten thousand twists and turns, it always flows eastward; this resembles mindfulness. Thus, when a gentleman sees a great body of water, he must indeed gaze intently upon it.”

孔子觀於東流之水子貢問於孔子曰君

子之所以見大水必觀焉者是何孔子曰

夫水大徧與諸生而無為也似德其流也

埤下裾拘必循其理似義其洸洸乎不淈

盡似道若有決行之其應佚若聲響其赴

百仞之谷不懼似勇主量必平似法盈不

求槩似正淖約微達似察以出以入以就

鮮絜似善化其萬拆也必東似志是故君

子見大水必觀焉

Source

Xun Kuang 荀況 (circa 310–238 B.C.E.), Xunzi 荀子 (Master Xun), juan 20, pp. 5b-6a. SKQS

First Spring Under Heaven

In 1784, the Qianlong emperor (1711–1799, reign 1735–1796) composed Record of Jade Spring Mountain, First Spring Under Heaven in which he concluded his study of water and advanced Jade Spring in the hills west of Beijing as the foremost freshwater spring of the imperium. Qianlong’s lengthy essay was included in “Forms of Natural Beauty,” the eighth chapter of Studies of Hearsay from Under the Sun, a compendium of notable things about Beijing that was published under imperial auspices in 1786.

Record of Jade Spring Mountain, First Spring Under Heaven

The virtue of water is that it nourishes humankind; its taste is delicate and sweet, and its quality, noble and light. This being so, these three are perfectly attuned to one another: being light, water’s taste is sweet, and drinking it purifies and enhances longevity. Thus, those who judge water always distinguish a spring water’s quality, high or low, by its lightness or heaviness.

We once commissioned a silver vessel to compare the relative weight of various waters. The water of Jade Spring of the Capital weighs one ounce. The water of Saishang at Yixun weighs one ounce. The water of Precious Pearl Spring of Jinan weighs one ounce and one ten thousandths. The water of Mount Jin Spring on the Yangzi weighs one ounce and three ten thousandths. These waters are therefore heavier than that of Jade Spring by one to three ten thousandths. As for the spring waters of Mount Hui and Pawing Tigers, each is heavier than Jade Spring by four ten thousandths; that of Mount Ping is heavier by six ten thousandths, and those of Pure Cool Spring, White Sand, Tiger Hill, and Green Cloud Temple on West Mountain are heavier than Jade Spring by a tenth. Theses comparisons were all reached while on inspection tours, the precise measurements acquired on Our command by Palace Attendants.

But is there none lighter than the water from Jade Spring? Yes. What spring? It is not a spring but snow water. Generally, We simply collect and boil it. It is lighter than Jade Spring by three ounces. Snow water cannot always be obtained, so of all the cold waters issuing from mountains, truly, there is none to surpass Jade Spring of the Capital.

In the past, according to the judgments of Lu Yu and Liu Bochu, either the water from the valley at Mount Lu was first or that from the Yangzi was first, that from Mount Hui was second. Though the southerners indeed enjoyed the benefit of their evaluations, regarding the comparative lightness or heaviness of water, Mount Hui doubtless should yield to the Yangzi. It should be appreciated that the elders did not speak hypothetically, but it is a pity that they not only did not reach Saishang at Yixun, they likewise did not reach Yanjing. As this is the case, Jade Spring is decidedly the First Under Heaven.

In recent years, the Western Sea was cleared to become Lake Kunming and in the region of Mount Wanshou there exist several famous springs. If all were traced to their very sources, then Jade Spring is the numinous artery, true and eminent, the heart of fine water. Moreover, its water is light and its taste is sweet, qualities that the water of Mount Lu cannot achieve and that, We believe, surpasses the water of Mount Jin along the Yangzi. Therefore, Jade Spring is designated First Spring Under Heaven. We order the establishment of the Chonghuan Shrine and a memorial carved in stone to support the Huiji River project. Construction at Jade Spring reinforces the base of Mount Baotu, flowing out to form a lake. Poets compare it to the Rainbow of the Waterfall. We inscribed the Eight Scenic Views of Mount Yan of bygone days; why not also follow in these footsteps and so on?

It is evident that there is justice in the world and falsehood in the world. The record is quite complete. Change is difficult. As for freshwater springs and humankind, there is virtue without resentment. Yet, one cannot avoid misrepresentation. Those Under Heaven who hold virtue and resentment can know fear yet need not be afraid.

御製玉泉山天下第一泉記

水之徳在養人其味貴甘其質貴輕然三者正相資質

輕者味必甘飲之而蠲疴益夀故辨水者恒於其質之

輕重分泉之髙下焉嘗製銀斗較之京師玉泉之水斗

重一兩塞上伊遜之水亦斗重一兩濟南珍珠泉斗重

一兩二釐揚子金山泉斗重一兩三釐則較玉泉重二

釐或三釐矣至惠山虎跑則各重玉泉四釐平山重六

釐清涼山白沙虎邱及西山之碧雲寺各重玉泉一分

是皆巡蹕所至命内侍精量而得者然則無更輕扵玉

泉之水者乎曰有為何泉曰非泉乃雪水也常収積素

而烹之較玉泉斗輕三釐雪水不可恒得則凡出山下

而有冽者誠無過京師之玊泉昔陸羽劉伯芻之論或

以廬山谷簾為第一或以揚子為第一惠山為第二雖

南人享帚之論也然以輕重較之惠山固應讓揚子具

見古人非臆説而惜其不但未至塞上伊遜並且未至

燕京若至此則定以玉泉為天下第一矣近嵗疏西海

為昆明湖萬夀山一帯率有名泉溯源會極則玉泉實

靈脉之發皇德水之樞紐且質輕而味甘廬山雖未到

信有過於揚子之金山者故定名為天下第一泉命將

作崇焕神祠以資惠濟而為記以勒石夫玉泉固趵突

山根蕩漾而成一湖者詩人乃比之飛瀑之垂虹即予

向日題燕山八景亦何嘗不隨聲云云足見公論在世

間誣辭亦在世間籍甚既成雌黄難易泉之於人有徳

而無怨猶不能免訛議焉則挾德怨以應天下者可以

知懼抑亦可以不必懼矣

Source

Yu Mingzhong 于敏中 (1714-1779) et al., Qinding Rixia jiuwen kao 欽定日下舊聞考 (Imperially Commissioned Studies of Hearsay from Under the Sun), juan 8, pp. 10b–12a.

Lu Yu’s Names

眠雲臥石

The Tang dynasty tea master Lu Yu 陸羽 (ca. 733-804 ca.) was known in his lifetime and throughout history by many names. The following appellations provide just some of the names by which he was known during his lifetime and by later writers.

Childhood names

Ji 疾, Malady, Blotchy, Deformity

Jici 季疵, Little Blemish

Surname and given names

Lu Yu 陸羽

Lu Ji 陸季

Lu Ji 陸疾

Surname and courtesy names

Lu Hongjian 陸鴻漸

Lu Jici 陸季疵

Lu Jibi 陸季庇

Aliases

Jingling zi 竟陵子, Master Jingling

Donggang zi 東崗子, Master East Ridge

Sangzhu weng 桑苧翁, Elder Mulberry and Nettle

Dongyuan zi 東園子, Master East Garden

Sobriquets

Lu san 陸三, Lu, The Third

Lu san shanren 陸三山人, Recluse Lu, The Third

Lu sheng 陸生, Sire Lu

Lu chushi 陸處士, Recluse Lu

Lu jushi 陸居士, Layman Lu

Lu Hongjian shanren 陸鴻漸山人, Recluse Lu Hongjian

Churen 楚人, Man of Chu

Chashan yushi 茶山御史, Tea Mountain Scribe

Dongyuan xiansheng 東園先生, Master East Garden

Honorifics

Lu Wenxue 陸文學, Imperial Instructor Lu

Lu Taizhu 陸太祝, Great Invocator Lu

Chadian 茶顛, Foremost Tea Master

Chasheng 茶聖, Tea Sage

Chaxian 茶仙, Tea Immortal

Chashen 茶神, Divinity of Tea

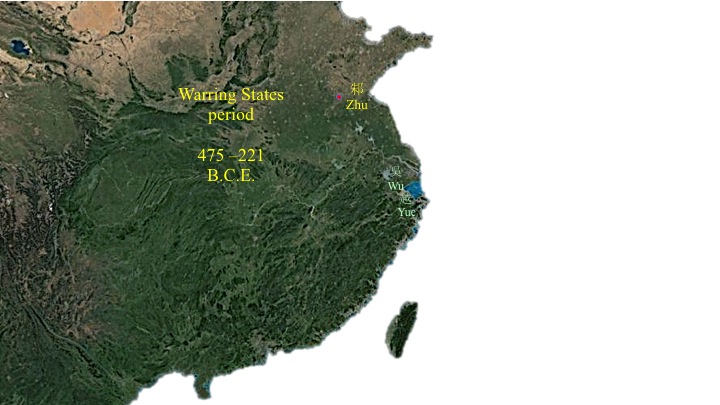

Tea in the Warring States Period

Tea was recently excavated from a royal tomb dating over 2,400 years ago to the late Zhou dynasty (1046-256 B.C.E.) and the period known as the Warring States (475-221 B.C.E.). The discovery was made in Shandong at Zoucheng, the capital of the ancient State of Zhu (11th-5th centuries B.C.E.). The archaeological find confirmed the early use of tea as a funerary offering to the dead and indicated its custom among the living. The archaeological context revealed not only the use of tea but also the likely source of the leaf. Moreover, the use of tea at so northerly a location advanced the geographical range of tea as an item of trade or tribute from tea producing regions south of the Yangzi.

In the eleventh century, during the inaugural years of the Zhou dynasty, the minor State of Zhu was created a vassal and tributary of the major State of Lu. Initially, the ruler of Zhu was ennobled viscount, a hereditary rank, and the state was established just southeast of Qufu, the capital of the State of Lu. Throughout its history, the State of Zhu was harried by its more powerful neighbors and was often forced to move its capital. In the ninth century, the Zhu territory and ruling house were divided to weaken the state. During the Spring and Autumn period, the State of Zhu regained strength. In 659, however, the bordering State of Lu defeated the State of Zhu in battle. In 643, the twelfth ruler of Zhu moved the capital farther southwest to Zoucheng. Over the centuries, nineteen Zhu sovereigns survived the political and military aggression of larger, neighboring states until the State of Zhu and its regnant family were destroyed in the later fifth century.

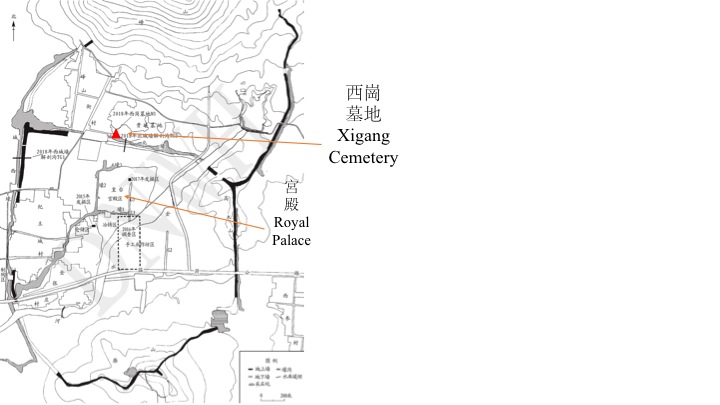

The capital city Zoucheng was strategically sited on the Jinshui River that flowed east to west through the flat, open plain between Mount Yi in the north and Mount Guo in the south. The precinct of the royal palace occupied the north-central axis of the city and was surrounded by a defensive trench and high walls of rammed earth. North of the palace and just beyond the protective ditch lay Xigang, the royal cemetery of the State of Zhu.

In 2018, excavations at Xigang revealed the graves of a Zhu monarch and his queen. Located side by side, each of the tombs was a deep pit constructed of rammed earth in the shape of a square with a wide entry ramp. The tomb of the queen, which was excavated first and designated Tomb M1, was found to have been repeatedly looted by thieves long ago. However, a number of remaining artifacts were discovered, including a pair of jade pendants, a small ring of jade, remnants of gilt and lacquer ware, and a cache of ceramics.

The store of pottery was uncovered on a narrow ledge cut into the south wall of the tomb above the floor of the grave. The earthenware and stoneware pottery were originally placed in a wooden chest that had since rotted away, leaving vessels – jars, large bowls, small cups, a lidded urn – and sherds in a jumble. Also on the ledge, two small stoneware bowls were found overturned, their interiors filled with soil. The earth of one of the bowls contained a dark plant material that was unidentified at the time of excavation but was retained for subsequent examination and testing.

In the past, tea remains from archaeological digs were identified by botanical morphology, the form and structure of the plant. Although the vegetal matter found at Xigang was rotted and blackened as to be unidentifiable by visual means, samples were later subjected to a battery of tests that found the cellular structure of the plant and the abundance of calcium salt crystals matched the genus Camellia. Likewise, the presence of caffeine and theanine identified the plant material as tea.

The remains of tea at Zoucheng were in a small bowl, one of two bowls of similar shape, size, and color that were discovered on the aforementioned ledge above the grave. The two bowls were reported as proto-porcelains, a ceramic type more accurately described as a high-fired porcelaneous stoneware with a greenish feldspathic iron glaze. On the basis of body, glaze, and style, the bowls and the other green-glazed stoneware in the cache were identified as Yue ware, imports from the distant pottery kilns of the southern states of Wu and Yue in Jiangsu and Zhejiang, the only fifth century sources of such early celadons.

As suggested by the Yue ware and its southern sources, the tea gardens of Jiangsu and Zhejiang were also the likely provenance of the leaves in the bowl. Aligned geographically along the eastern seaboard and latticed with transport waterways, the lower reaches of Shandong and the upper stretches of Jiangsu and Zhejiang exchanged tea and ceramics through trade or tribute. Located just south of Zhu, Wu and Yue were nearer sources of tea than the distant tea producing regions of the State of Chu or Sichuan.

It is also noteworthy that nearly all of the ceramics found in Zoucheng Tomb M1 were coupled with vessels of a similar size and shape: two large jars, two pairs of smaller jars, two large bowls, two small bowls, and two small cups; the only exception to pairing was the single lidded urn. Also, the two small bowls appeared distinct from the cache of ceramics by their location, association, and contents. Whereas the other potteries were empty and stored as a group in the wooden case, the two bowls were found separate from the rest, close together, and out on the ledge. Notably, the one bowl contained tea, a comestible that in the context of ritual burial customarily signified ceremonial sacrifice by the living to the dead.

The discoveries in Shandong document not only the earliest evidence to date for the use of tea during historical times but also the earliest use of tea as a funerary offering. Prior to the archaeological finds at Zoucheng, the earliest tea as sacrifice was dated to the second century B.C.E. and excavated from Han Yangling, the mausoleum of the Han emperor Jingdi at Xi’an nearly five hundred miles away to the west in Shaanxi.

Significantly, the concurrence of tea and Yue ware at Zoucheng marked the beginnings of the ancient and enduring tradition that intimately connected the art of tea with the use of celadon, a practice promoted by the Tang tea master Lu Yu in the Book of Tea in which he famously compared the white wares of Xing to the celadons of Yue:

There are those who judge bowls from Xing superior to ones from Yue. This is certainly not so. If Xing is like silver, then Yue is like jade. This is the first way in which Xing cannot compare to Yue. If Xing is like snow, then Yue is like ice. This is the second way in which Xing cannot compare to Yue. Xing ware is white, and thus the color of liquid tea in the bowl looks reddish. Yue ware is celadon, and thus the color of tea appears greenish. This is the third way in which Xing cannot compare to Yue.

References

Lu Guoquan 路國權 et al., “Shandong Zoucheng shi Zhuguo gucheng yizhi 2015 nian fajue jianbao 山東鄒城市邾國故城遺址2015年發掘簡報 (Brief Report on the 2015 Excavation of the Ruins of the Ancient Capital of the State of Zhu, Shandong),” Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) (2018), no. 3, pp. 44-67.

Ma Fangqing 馬方青 et al., “Shandong Zoucheng Zhuguo gucheng yizhi 2021 nian fajue chutu zhiwu da yicun fenxi — jiyi gudai chengshi guanli shijiaozhong de ren yu zhiwu 山東鄒城邾國故城遺址2015年發掘 — 出土植物大遺存分析 (Plant Macro Remains Excavated from the Ancient Capital City Site of the State of Zhu in Zoucheng, Shandong Province in 2015: Humans and Plants in the Perspective of Ancient Urban Management),” Kaogu tansuo 考古探索 (Archaeology Discovery) (4 March 2019), pp. 57–69. Accessed 26 January 2022. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333973022).

Wang Qing 王青et al., “Shandong Zoucheng Zhuguo gucheng yizhi 2015–2018 nian tianye kaogu de zhuyao shouhuo 山東鄒城邾國故城遺址 2015–2018 年 田野考古的主要收獲 (The Primary Findings from the Field Archaeology at the Ruins of the Ancient Capital of the State of Zhu in Zoucheng, Shandong),” Tongnan wenhua 東南文化 (Southeast Culture) (2019), vol. 3, no. 269, pp. 18–24, pls. 1–3.

Jiang Jianrong et al., “The Analysis and Identification of Charred Suspected Tea Remains Unearthed from Warring State Period Tomb,” Scientific Reports (August, 2021), no 11. Accessed 26 January 2022. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353929508).

Lu Guoquan 路國權 et al., “Shandong Zoucheng Zhuguo gucheng Xigang mudi yihao Zhanguo mu chaye yicun fenxi 山東鄒城邾國故城西崗墓地一號戰國墓茶葉遺存分析 (Analysis of Tea Leaf Remains of Number 1 Warring States Tomb at Xigang Cemetery, the Ancient Capital of the State of Zhu, Zoucheng, Shandong), Kaogu yu wenwu 考古與文物 (Archaeology and Cultural Relics)( September, 2021), no. 5, pp. 118-122.

Lament at the Stupa of Jiaoran and the Tomb of Lu Yu

眠雲臥石

Meng Jiao of the Tang dynasty

Accompanying Lu Cheng Back to Huzhou, I Composed a Lament to the Dead at the Stupa of Jiaoran and the Tomb of Lu Yu

Pouring rain before the temple,

Pale waterclover gathers in the freshening wind.

Past poetry filled with friendship,

Now my poems, empty.

The lonely moan of the jade flute, doleful,

Distant thoughts, the vista – lush.

Here, the brick stupa of the Zen Master of Mount Zhu.

Here, the Jingling Elder of the Endless Night.

The sound of grasses and trees, profuse

As if filled with a sense of wisdom

By you and all your verses,

Abundant and amassed.

Pursuing poetry, you once said,

Of verse, there truly was no lack.

Yet a river’s song is hard to repeat

And the dust of the capital fills only the body.

Sending you astream, two mandarins,

Colors paired, flying east.

High and serene, the Eastern Realm,

Beautiful abode, cold and sublime.

My hands gather your treasured works,

Offerings that foster joy and full harmony.

Embracing them gratefully at the end,

Not at the pavilion on the banks of the Luo

But at Death, the Great Unity.

唐 孟郊

送陸暢歸湖州因憑吊故人皎然塔陸羽墳

淼淼霅寺前 白蘋多清風

昔游詩會滿 今游詩會空

孤吟玉淒惻 遠思景蒙籠

杼山磚塔禪 竟陵廣宵翁

饒彼草木聲 仿佛聞餘聰

因君寄數句 遍為書其叢

追吟當時說 來者實不窮

江調難再得 京塵徒滿躬

送君溪鴛鴦 彩色雙飛東

東多高靜鄉 芳宅冬亦崇

手自擷甘旨 供養歡沖融

待我遂前心 收拾使有終

不然洛岸亭 歸死為大同

全唐詩 juan 379, p. 8b.

The Censor’s Jar

An unusual account of tea was once written by a high court official during the eighth century. The report described the tea used in the offices of the Censorate, one the most powerful and feared agencies of the Tang imperial government.

The Censor’s Jar —The Censorate is comprised of three Bureaus: Headquarters Bureau, its personnel are called Attendant Censors; Palace Bureau, its personnel are called Palace Censors; and Investigation Bureau, its personnel are called Investigation Censors. The Investigation Bureau is located to the south. At the beginning of the Huichang reign period, the Investigation Bureau was renovated by the Investigating Censor Zheng Lu. The Investigation Hall of the Ministry of Rites is called the Hall of Pines, for to its south there are ancient pines. The Investigation Hall of the Ministry of Justice is called the Hall of Nightmares, for being held there causes many bad dreams. The Investigation Hall of the Ministry of War is responsible for the tea for the Bureaus. The tea must be the finest from the markets of Shu. It is stored in a ceramic vessel to protect it from heat and moisture. A censor personally oversees its care. Therefore, it is called the Censor’s Tea Jar.

御史瓶. 御史三院. 一曰臺院. 其僚曰侍御史. 二曰殿院. 其僚曰殿中侍御史. 三曰察院. 其僚曰監察御史. 察院㕔居南. 㑹昌初. 監察御史鄭路所葺. 禮祭廳謂之松廳. 南有古松也. 刑察廳謂之魘廳. 寢於此多魘. 兵察廳常主院中茶. 茶必市蜀之佳者. 貯於陶噐. 以防暑濕. 御史躬親監啟. 故謂之御史茶瓶.

New York

The Yushi ping 御史瓶 or Censor’s Jar was an entry in Record of the Censorate, a twelve-volume work that described the Tang imperial investigative organization known as the Censorate. The study was written by Han Wan 韓琬 (active 710–741), a Palace Censor who revealed the inner workings of the Censorate through nearly a century of its history. A direct witness to the inner workings of the agency, Han Wan detailed the matters of the Bureau through its registers, records, and biographies, including the establishment of the intelligence service, its sources and development, and its handling of official affairs and conduct.

According to Han Wan, tea was so essential to the daily operations of the Censorate that a ministry office was charged with its procurement and no less a senior officer than an imperial censor was charged with managing its storage. The quality of the tea was described as necessarily the best leaf from Shu, its most ancient source in Sichuan. Such was the importance of tea that its very repository was named yushi chaping 御史茶瓶, the Censor’s Tea Jar.

Han Wan was a native of Nanyang, Dengzhou in present Henan. While it was unclear from his Record as to whether or not he was a tea drinker, Han Wan appreciated the herb and its use by the Censorate to make exceptional note of it in his historical account. Moreover, subsequent records such as the Record of Things Heard and Seen testify to the informed interest in tea by later members of the Censorate, including the agency leaders Vice Censor-in-Chief Feng Yan 封演 (js 756) and the Censor-in-Chief Li Jiqing 李季卿 (709–767). Han Wan’s record of the Censor’s Jar was but one of a number of expressions of the utility and esteem of tea among the highest eschelons of the Tang imperial administration, especially northern elites.

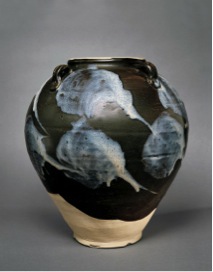

Figure

A Large Blue-Splashed Brown-Glazed Stoneware Jar

Tang Dynasty, 8th – 9th Century

Height 16 inches (40.6 cm.)

J. J. Lally & Company

Oriental Art

New York, New York

Notes

Huichang 㑹昌 reign period (841–847).

Zheng Lu: 鄭路 (active ca. 841–847), an Erudite of the Court of Imperial Sacrifices and an Investigating Censor.

Record of the Censorate: Yushi taiji 御史臺記, after 741.

Record of Things Heard and Seen: Fengshi wenjian ji 封氏聞見記, ca. 772.

Sources

Tang yulin 唐語林 (Forest of Discussions of the Tang). Wang Dang 王讜 (active 1089), juan 8, pp. 7a-7b. SKQS.

Yinhua lu因話錄 (Tales of Retribution, 9th century). Compiled by Zhao Lin趙璘 (js 834), juan 5, p. 4b. SKQS.

Yuding yuanjian leihan 御定淵鑑類函 (The Categorized Caseworks of the Yuanjian Studio by Imperial Commission, 1710). Compiled by Zhang Ying張英 (js 1667, 1637-1708), juan 395, pp. 11b-12a. SKQS.

Zhongguo chaye lishi ziliao xuanji 中國茶葉歷史資料選輯 (A Compilation of Historical Materials on Chinese Tea). Compiled by Chen Zugui 陳祖槼 and Zhu Zizhen 朱自振, p. 210. Beijing: Nongye chuban she, 1981.

Poem

Wang Fuli of the Qing Dynasty

Poem

Dawn flower, evening moon

Worthy host, splendid guest

Speaking freely of past and present

Tasting tea, one after another…

Between Heaven and Earth, is there anything more enjoyable?

清 王復禮

花晨月夕

賢主嘉賔

縱談古今

品茶次苐

天壤間更有何樂

Notes

Wang Fuli 王復禮 (Wang Caotang 王草堂, ca. 1641-1720), from Hangzhou.

Source

Lu Tingcan

陸廷燦 (active ca. 1666/1678–1743), Xu Chajing 續茶經 (Sequal to the Book of Tea,

1734), juan 下之二,

p.18b. SKQS.

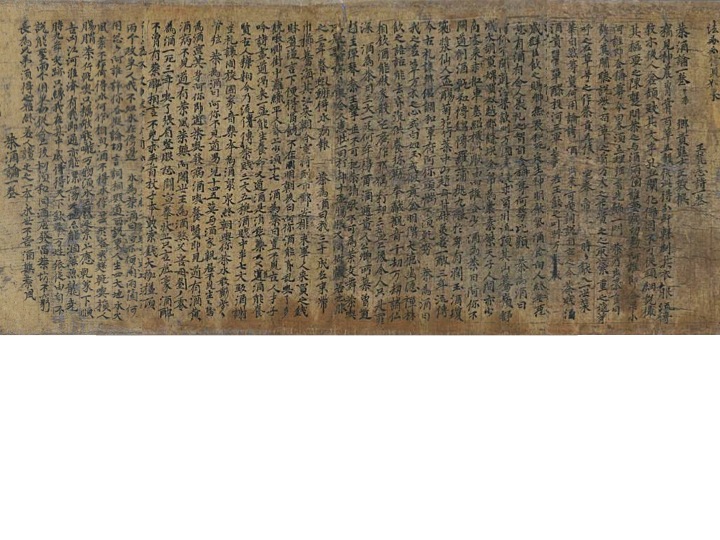

Discourse Between Tea and Wine

Discourse Between Tea and Wine,

ca. 742-760, one juan and

preface

by the Presented Prefectural Nominee, Wang Fu (ca. mid 8th century)

I dare say that Shennong the Divine Cultivator tasted the Hundred Plants, and thereafter the Five Grains were distinct; that Xuanyuan the Yellow Emperor created clothing and passed it down to instruct posterity; that Cang Jie created words; and that Confucius spread the Ru doctrines. At present, such things cannot present be spoken in depth, so I select only the essentials for discussion. Now, I ask Tea and Wine, who of the two has more virtue? Who is inferior? Who is superior? Today, each must form arguments, and the greater will lead in gaining glory for its side.”

Tea then comes forth saying, “Everyone, do not quibble, for it is said that I am the first of the Hundred Plants and the flower of the Ten Thousand Plants. The most precious part is sought from my pistils, the most important is chosen from my buds. I am called Mingcao; my sobriquet is Cha. I am sent as tribute to the households of the Five Marquises, and offered to the families of the Emperor and Princes. It is fashionable to gift me, engendering a lifetime of honor and glory. Naturally, I am the respected one. Why the need for debate and boasting!”

Wine then comes forth, “What silly words! Since antiquity till now, tea has been scorned while wine has been respected. Cast a bucket of wine lees in the river, and the Three Armies report in drunk. When lords and rulers drink wine, everyone shouts ‘longevity of ten-thousand years.’ When the assembled courtiers drink wine, all may speak without fear. I comfort the dead and calm the living, and even the divine are pleased by my fragrance. When wine and food are shared, evil intent is always absent. When there is wine, there is order: benevolence, righteousness, propriety, and wisdom. Naturally, I’m called superior. So why bother comparing!”

Tea says to Wine, “Ah, you have not heard: the Ten Thousand States come seeking the tea of Fuliang and Shezhou. For tea from mountains of Shu and Mengding, people scale the massif peaks. In Shucheng and Taihu, they procure maids and buy slaves. In Yuejun and Yuhang, tea is kept in pouches made of gold and silk. The tea Pale Purple Emperor is rare in the world. When tea merchants come bidding, their boats and carriages snarl in the traffic. According to this reasoning, who is inferior now?”

Wine says to Tea, “Well, you haven’t heard. Jijiu and Qianhe wines are traded for brocade and gauze. Grape and Jiuyun wines benefit the body. Jade and Qiongjiang wines fill the goblets of immortals. The wines Chrysanthemum Flower and Bamboo Leaf are passed among lords and princes. The Zhaomu wines of Zhongshan are sweet and pleasingly bitter. One cup inebriates a person for three years, so says a legend passed from antiquity till today. Wine inspires comity among the plebeian and pacifies the martial. So, there’s no need to worry your head.”

Tea says to Wine, “As Mingcao, I am the heart of the Ten Thousand Plants. I am as white as jade or like yellow gold. Famous monks of great virtue and hermits of Chan monasteries all drink me during discourse, for I drive away weariness. Tea is offered to Maitreya and dedicated to Avalokiteśvara. Spanning a thousand katalpas, ten thousand aeons, the Buddhas all venerate me. Wine can ruin families and scatter households and spread immorality and depravity. Drinking three cups of wine causes only greater iniquity.”

Wine says to Tea, “At just three coins a jar, when will tea ever make for wealth? Wine reaches the nobility and is admired by court officials. It once inspired the King of Zhao to pluck the zither and the King of Qin to strike musical ceramics. It is not permitted for tea to accompany singing nor is it allowed for tea to rouse dancing. To drink tea is only to get backaches, and drinking too much causes stomach pains. If ten cups a day are downed, the intestines swell like yamen drums. Taking tea for three years is to spur dropsy in a toad.”

Tea says to Wine, “Of my generation, I am celebrated, properly attired, girdled and groomed. Leaping oceans and riding rivers, I arrive at this golden court. In the marketplace, dealings are never certain. But people come to buy me, their money overflowing. Even as we speak, I easily attain wealth and riches, no waiting for tomorrow morning or the day after. Oh, Wine, you make people dull and confused. Drinking too much, they become garrulous. In the street, you ensnare them. You deserve at least seventeen lashes!”

Wine says to Tea, “Don’t you know about the talented men of antiquity, who chanted poetry and said, ‘When thirsty, drink a cup of wine to rejuvenate and nurture life.’ And,‘Wine is the medicine that purges all worries.’ Or, ‘Wine can cultivate virtue.’ These sayings from the ancients have passed down till today. Tea is cheap, three coins for five bowls; and while wine is also cheap, it still costs seven coins for just half a cup. Serving wine and formal seating are ceremonies for guests. Ritual state music flows from the fountain of wine. But drink tea when court is ended and none dare tweet or strum even a bit.”

Tea says to Wine, “So, you do not believe that youths of fourteen or fifteen should not visit wine shops. You do not think that the shengsheng bird lost its life because of wine. You said, ‘Tea drinking tea causes disease and drinking wine cultivates virtue.’ But although I have seen jaundice and disease due to wine, I have never seen madness or insanity from tea. Because of wine, King Ajātaśatru killed his father and distressed his mother, and Liu Ling died in three years. Having drunk wine, the brows arch, the eyes bulge, angry fights start, and fisticuffs declared. Rough paladins are accused of drunkenness, but that can never be said of tea. Inescapably, the drunkard is arrested and imprisoned, the law fines him, a great cangue put round his neck, and his back beaten. To abstain from wine, he will burn incense, cry to Buddha, and beseech Heaven. For the rest of his days, he will not drink, hoping to avoid faltering on the path to sobriety.” Tea and Wine vie to distinguish one from the other, unaware that Water is right next to them.”

Water says to Tea, “The two of you, why so vehement! Who are you to argue about virtues? Speaking so, you ruin one another with nonsense. In life, there are four essential elements: Earth, Water, Fire and Wind. Tea without water, how does that look? Wine without water, how does that appear? Rice and leavening eaten dry injures the intestines and stomach. Caked tea swallowed dry scrapes and wounds the throat. All living things need water, the source of the Five Grains. From above, I respond to celestial signs; from below, I follow the auspicious and dreadful. By me, the rivers Yangzi, Yellow, Huai, and Ji all flow. I can inundate Heaven and Earth. I can wither and kill the fishes and dragons. In the age of Yao, the Nine Years of Floods were caused by me. I am worshipped by All Under Heaven, and the Ten Thousand Clans obey me. While I am no saint, why do you two argue your merits? From now on, be in harmony, so that wineshops prosper and teahouses are not impoverished. Be everlasting brothers, from beginning to end. When people read this, generations for eternity will never suffer madness from wine nor insanity from tea.”

Discourse Between Tea and Wine, one juan.

A manuscript written by Yan Haizhen, disciple of the Zhishu Monastery, on

the fourteenth day of the first lunar month of the third year of the Kaibao

reign period, 970.

茶酒論一卷並序

鄉貢進士王敷撰

竊見神農曾嘗百草, 五穀從此得分, 軒轅製其衣服, 流傳教示後人; 倉頡致其文字, 孔丘闡化儒因. 不可從頭細説, 撮其樞要之陳. 暫問茶之與酒, 兩個誰有功勛? 阿誰即合卑小, 阿誰即合稱尊? 今日各須立理, 強者光飾一門.

茶乃出來言曰: 諸人莫閙, 聼說些些, 百草之首, 萬木之花. 貴之取蘂, 重 之摘芽. 呼之茗草, 號之作茶. 貢五侯宅, 奉帝王家. 時新獻入, 一世榮華. 自然 尊貴, 何用論誇!

酒乃出來: 可笑詞說! 自古至今, 茶賤酒貴. 單醪投河, 三軍告醉. 君王飲之, 叫呼萬歲. 群臣飲之, 賜卿無畏. 和死定生, 神明歆氣. 酒食向人, 終無惡意. 有酒有令, 仁義禮智. 自合稱尊, 何勞比類.

茶為酒曰: 阿你不聞道: 浮梁歙州, 萬國來求. 蜀山蒙頂, 其山驀嶺. 舒城, 太湖, 買婢買奴.越郡, 餘杭, 金帛為囊. 素紫天子, 人間亦少. 商客來求, 船車塞紹. 據此蹤由, 阿誰合小?

酒為茶曰: 阿你不聞道. 齊酒, 乾和, 博錦, 博羅. 蒲桃, 九醖, 於身有潤. 玉酒, 瓊漿, 仙人盃觴. 菊花, 竹葉, 君王交接. 中山趙母, 甘甜美苦. 一醉三 年, 流傳今古. 禮讓鄉閭, 調和軍府. 阿你頭腦, 不須乾努.

茶為酒曰: 我之茗草, 萬木之心. 或白如玉, 或似黃金. 名僧大德, 幽隱禪林. 飲之語話, 能去昏沉. 供養彌勒, 奉獻觀音. 千劫萬劫, 諸佛相欽. 酒能破家 散宅, 廣作邪淫. 打卻三盞已后, 令人只是罪深.

酒為茶曰: 三文一瓨, 何年得富? 酒通貴人, 公卿所慕. 曾遣趙王彈琴, 秦王擊缶. 不可把茶請歌, 不可為茶教舞. 茶喫只是腰疼, 多喫令人患肚. 一日打却 十盃, 腹脹又同衙鼓. 若也服之三年, 養蛤蟆得水病報.

茶為酒曰: 我三十成名, 束帶巾櫛. 驀海騎江, 來朝金室. 將到市鄽, 安排未畢. 人來買之, 錢財盈溢. 言下便得富饒, 不在明朝後日. 阿你酒能昏亂, 喫了多 饒啾唧. 街中羅織平人, 脊上少須十七!

酒為茶曰: 豈不見古人才子, 吟詩盡道: 渴來一盞, 能生養命. 又道: 酒是消愁藥 . 又道: 酒能養賢. 古人糟粕, 今乃流傳. 茶賤三文五碗, 酒賤中半七文. 致酒謝坐. 禮讓周旋. 國家音樂, 本為酒泉. 終朝喫你茶水, 敢動些些管弦.

茶為酒曰: 阿你不見道: 男兒十四五, 莫與酒家親. 君不見猩猩鳥, 為酒喪 其身. 阿你即道: 茶喫發病, 酒喫養賢. 即見道有酒黃酒病, 不見道有茶瘋茶癲. 阿闍世王為酒殺父害母, 劉伶為酒一死三年. 喫了張眉竪眼, 怒鬥宣拳. 狀麤豪酒醉, 不曾有茶醉相言. 不免求首杖子, 本典索錢. 大枷搕項, 背上抛椽. 便即燒香斷酒, 念佛求天, 終生不喫, 望免迍邅. 兩個政爭人我, 不知水在傍邊。

水為謂茶曰: 阿你兩個, 何用怱怱! 阿誰許你, 各擬論功? 言詞相毀, 道西說東. 人生四大, 地水火風. 茶不得水, 作何相貌? 酒不得水, 作甚形容? 米麯乾喫, 損人腸胃. 茶片乾喫, 只糲破喉嚨. 萬物須水, 五穀之宗. 上應乾象, 下順吉凶. 江河淮濟, 有我即通. 亦能漂蕩天地, 亦能凅殺魚龍. 堯時九年災跡, 只緣我在其中. 感得天下欽奉, 萬姓依從. 由自不說能聖, 兩個用爭功? 從今以後, 切須和同. 酒店發富, 茶坊不窮. 長為兄弟, 須得始終. 若人讀之一本, 永世不害酒癲茶瘋.

茶酒論一卷

開寶三年庚午歲正月十四日知術院弟子閻海真自手書記

Bibliography

Benn, James A. “Buddhism, Alcohol, and Tea in Medieval China.” Of Tripod and Palate: Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China. Edited by Roel Sterckx, pp. 213-236. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Cha jiu lun 茶酒論 (Discourse Between Tea and Wine, ca. 760).” By Wang Fu 王敷 (ca. mid 8th century). In Zhongguo gudai chaye quanshu, 中國古代茶葉全書 (Compendium of Books on Ancient Chinese Tea). Compiled by Ruan Haogeng 阮浩耕 et al., pp. 39-40. Hangzhou: Zhejiang sheying chuban she, 1999.

Dunhuang bianwen ji xinshu 敦煌變文集新書 (New Collection of Transformational Texts from Dunhuang). Edited by Pan Chonggui潘重規. Beijing: Wenjin chuban she, 1994.

Dunhuang bianwen jiaozhu 敦煌變文校注 (Annotations to the Transformation Texts of Dunhuang). Edited by Huang Zheng 黃征 and Zhang Yongquan 張涌泉, vol. 3, pp. 423-433. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1997.

Mair, Victor H. and Erling Hoh. “Appendix B: A Debate Between Tea and Beer.” The True History of Tea. London: Thames and Hudson, 2009.

Pearse, Amy. “Negotiating Religious and Cultural Diversity in Tang China: An Analysis of the Cha jiu lun 茶酒論,” The Student Researcher, vol. 4, no. 1 (May 2017), pp. 45–55.

Tseng Chin-Yin. “Appendix A: Debate Between Tea and Alcohol.” Tea Discourse in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE): Conceptions of Social Engagements. A.M. diss., Harvard University, 2008.

Wang Fu 王 敷. Cha jiu lun 茶酒論 (Discourse Between Tea and Wine). Scroll: ink on paper. 41.1 x 41.6 cm. Pelliot Chinois 2718. Département des Manuscrits, Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Zhongguo lidai chashu huibian jiaozhu ben 中國歷代茶書匯編校注本 (Annotated Compilation of Tea Books of Dynastic China). Compiled by Zheng Peikai 鄭培凱 and Zhu Zizhen 朱自振 (1934–present), vol. 1, pp. 42 and 43, n. 1. Hong Kong: Commercial Press, 2014.

Offering Matching Rhymes to Pi Rixiu’s Ten Songs on Tea

Lu Guimeng of the Tang dynasty

Offering Matching Rhymes to Pi Rixiu’s Ten Songs on Tea

陸龜蒙

奉和襲美茶具十詠

Tea Garden

The way to tea concealed, winding round in twists and turns,

A walk in the wild in countless circles.

Sunward, tea grows close and dense;

Shaded, small and sparse.

The women — entwined clouds of hair — languid.

The tea — piled into scent filled baskets — scant.

Where shall we gather?

Atop the cliffs on a dewy spring morning.

茶塢

茗地曲隈回

野行多繚繞

向陽就中密

背澗差還少

遙盤雲髻慢

亂簇香篝小

何處好幽期

滿岩春露曉

Teaist

The divinely endowed know the herb of immortality,

Naturally and simply.

Coming at leisure to the north side of the mountain,

Greeting the east wind.

After the Grain Rains, seeking the ephemeral fragrance

Among the clouds, high and far from the path;

Waiting for the call of the bird of spring

To enlighten me.

茶人

天賦識靈草

自然鍾野姿

閑來北山下

似與東風期

雨後探芳去

雲間幽路危

唯應報春鳥

得共斯人知

Tea Shoot

The bud embodies profound harmony;

Spring rouses the jade sprout.

As light mists infuse and refine essence,

The tender nub forms.

It seeks the purple haze of dawn,

Desires the warmth of red clouds.

Such beauty is hard to come by —

Like an upended basket never filled.

茶筍

所孕和氣深

時抽玉苕短

輕煙漸結華

嫩蘂初成管

尋來青靄曙

欲去紅雲煖

秀色自難逢

傾筐不曾滿

Tea Basket

The gold blade splits jade bamboo; strips

Woven into oblique ripples.

Made by the village elder,

Carried by the mountain maiden.

Yesterday, smoke stained and blistered;

Today, holding the morning’s green pickings.

Contending songs, teasing chants;

At eventide, returning home.

茶籝

金刀劈翠筠

織似波文斜

制作自野老

攜持伴山娃

昨日斗煙粒

今朝貯綠華

爭歌調笑曲

日暮方還家

Tea Hut

Wandering the mountain, searching for wood

To build a place in the foothills.

The gate bows by a bend in the stream,

The wall hugs the curve of the cliff.

In the morning, scattering with the birds,

In the evening, resting with the clouds.

Undaunted by the toil of picking,

Worrying only of fulfilling the tribute.

茶舍

旋取山上材

駕為山下屋

門因水勢斜

壁任岩隈曲

朝隨鳥俱散

暮與雲同宿

不憚採掇勞

隻憂官未足

Tea Stove

Without a chimney, it contains a light steam,

A mist reflecting the first rays of the sun.

Fill the cauldron with jade pure spring water to boil,

Fill the steamer with soft buds to cook.

The rare fragrance perpetuates the spring season;

The fair delicate hue, like the fall chrysanthemum.

Those tending the fire are like my disciples, of whom

Year after year I can never see enough.

茶竈

無突抱輕嵐

有煙映初旭

盈鍋玉泉沸

滿甑雲芽熟

奇香襲春桂

嫩色凌秋菊

煬者若吾徒

年年看不足

Tea Hearth

All around, pounding tea into pulp;

Dawn to dusk, slender wisps of smoke rise.

Square or round, tea molded into various shapes;

Arranged in order, layers dried in rotation,

High to low, like rounds of mountain songs.

After drying tea, the hearths return to daily use:

In truth, those tending the hearths

Usually dry preserved flowers.

茶焙

左右搗凝膏

朝昏布煙縷

方圓隨樣拍

次第依層取

山謠縱高下

火候還文武

見說焙前人

時時炙花脯

Tea Brazier

Fresh spring water tastes fine;

The old iron brazier looks foul.

How is a night of wind and snow endured

Without like-minded friends of mist and haze?

We once crossed below Red Rock

And rested among the fine tea at the mouth of Clear Stream.

Carelessly, we were offered a coarse turbid bitter brew…

Was there any need then to dispense with the wine?

茶鼎

新泉氣味良

古鐵形狀醜

那堪風雪夜

更值煙霞友

曾過赪石下

又住清溪口

且共薦皋盧

何勞傾斗酒

Tea Bowl

The ancients prized the bowl and stand

As a seductively expressive adornment.

But can it have the elegance of the jade tablet and disc

Or the delicacy of hazy mountain mists?

Perhaps to grace and enhance the bamboo mat,

To harmonize and refine the golden wine jar.

But to make a moral and superior gentleman?

This has never been known before.

茶甌

昔人謝塸埞

徒為妍詞飾

豈如珪璧姿

又有煙嵐色

光參筠席上

韻雅金罍側

直使於闐君

從來未嘗識

Tea Brewing

Sitting leisurely among the pines,

Watching the simmer of snow swept from their branches.

When the water roils,

Add the blue green powdered leaf.

Overflowing with lively essence,

Vanquishing malaise, such tea is

Unsuited to reading palace documents,

But proper to peeking at jade scrolls of the immortals.

煮茶

閑來松間坐

看煮松上雪

時於浪花裡

並下藍英末

傾余精爽健

忽似氛埃滅

不合別觀書

但宜窺玉札

Source

Lu Guimeng陸龜蒙 (?-881), “Fenghe Ximei chaju shiyong 奉和襲美茶具十詠 (Offering Matching Rhymes to Pi Rixiu’s Ten Songs on Tea)” in Cao Yin 曹寅 (1658-1712 A.D.) and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645-1719 A.D.) et al., comps, Quan Tangshi 全唐詩 (Complete Poetry of the Tang Dynasty, 1705), ch. 620, nos. 47-56.

Notes

Lu Guimeng wrote the poems in response to a set of ten tea poems by his friend Pi Rixiu 皮日休 (834-883 A.D.). For a translation of the original themes and poems of Pi Rixiu, see tsiosophy.com/2018/07/miscellaneous-rhymes-tea/